Language never sits still. Words and expressions pick up stories as they move through time, and some of our most harmless-sounding phrases today actually come from a world of filthy toilets, poachers, hangings, and holy terror.

Here are 15 common sayings that carry very medieval baggage—some funny, some grim, and some downright disgusting.

1. “The Wrong End of the Stick”

Today, if you’ve “got the wrong end of the stick,” you’ve simply misunderstood something.

In the Middle Ages, it was much worse.

Public latrines were long stone benches with holes cut side by side. There was no toilet paper, just a communal sponge on a stick, soaking in vinegar or salt water between uses. This was passed along from person to person.

If you grabbed that stick the wrong way round… well, let’s just say misunderstanding wasn’t your biggest problem.

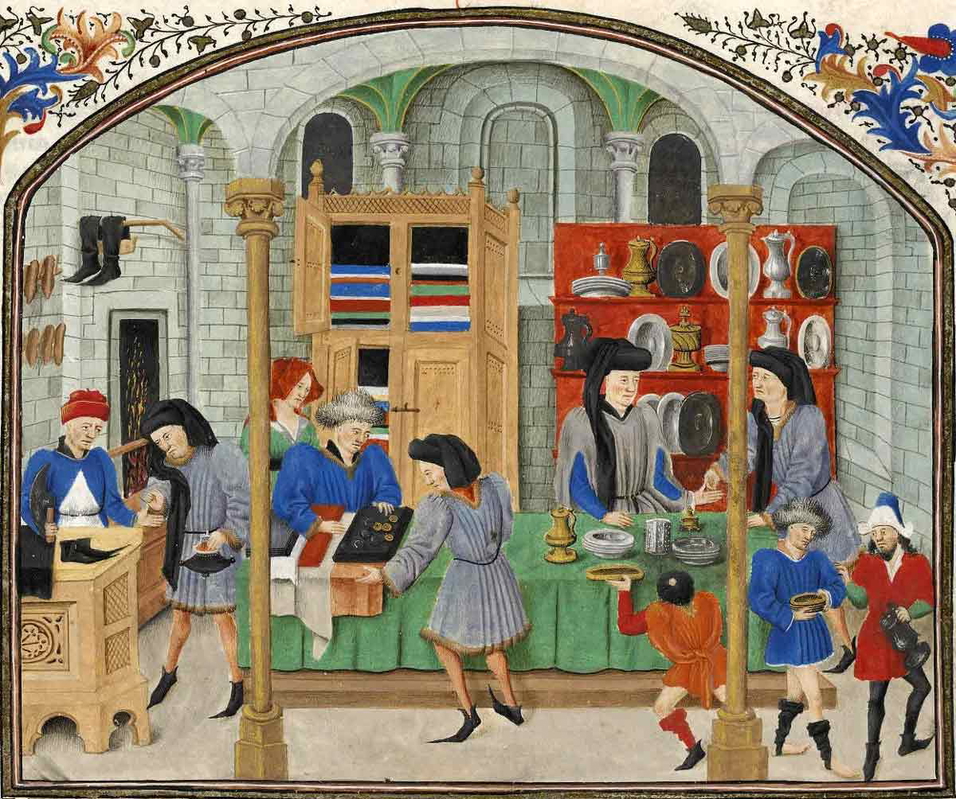

2. “A Pig in a Poke”

Buying “a pig in a poke” warns against accepting something unseen or unchecked.

In medieval markets, meat and small animals were often handed over in a cloth bag called a poke. A careless buyer who didn’t look inside might get home and discover they’d been given something much less appealing than a pig. The phrase became a warning: don’t accept what you haven’t inspected.

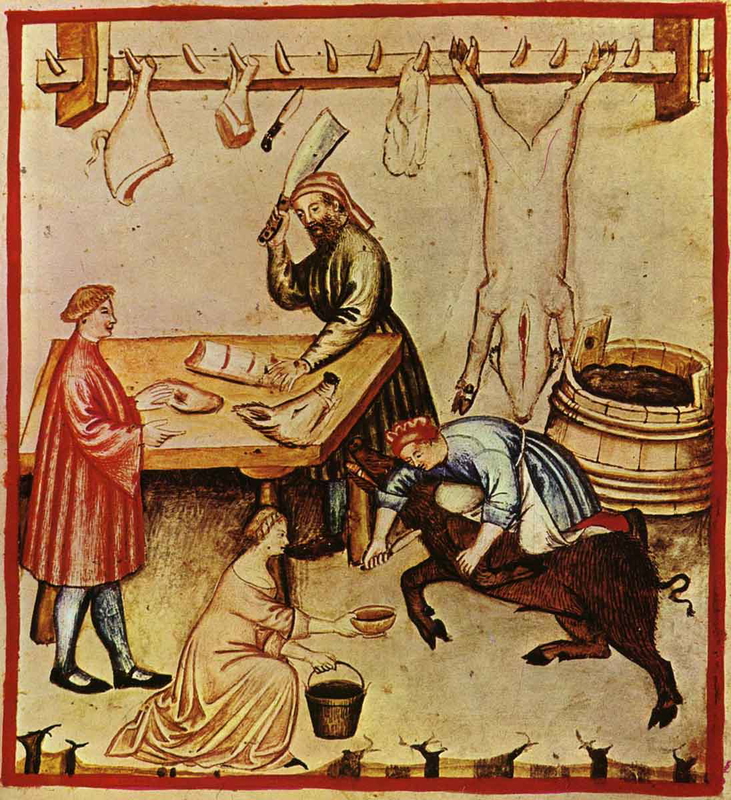

3. “Eat Humble Pie”

If you “eat humble pie” today, you’re swallowing your pride and admitting you were wrong.

Originally, it was about what you ate—literally. After an animal was butchered, the choicest cuts went to nobles. The leftovers—liver, lungs, and other offal—were minced and baked into pies for poorer people. These were called “umble pies”, from a word related to the animal’s innards.

Over time, “umble pie” merged with “humble,” and the idea of being given the cheap bits turned into a metaphor for being put in your place.

4. “By Hook or By Crook”

“By hook or by crook” now means achieving something by any means necessary.

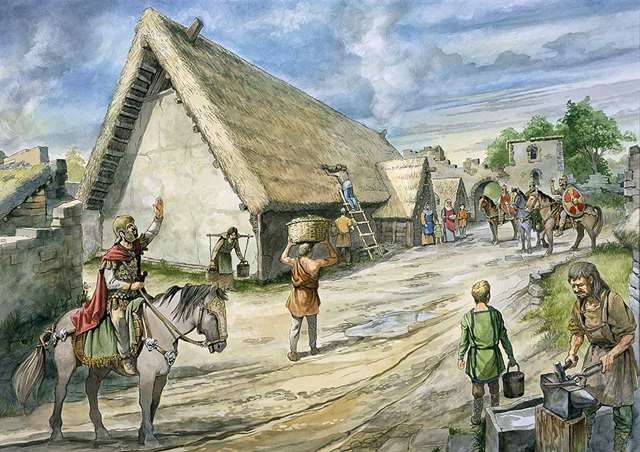

The phrase probably goes back to medieval forest law, when most forests belonged to the crown. Commoners were allowed to collect bits of wood, but not to cut branches off trees using tools like a billhook, or to pull them down with a shepherd’s crook.

In reality, many people likely ignored these rules and used those tools anyway to get more than they were strictly allowed. They got their firewood “by hook or by crook”—by fair means or foul.

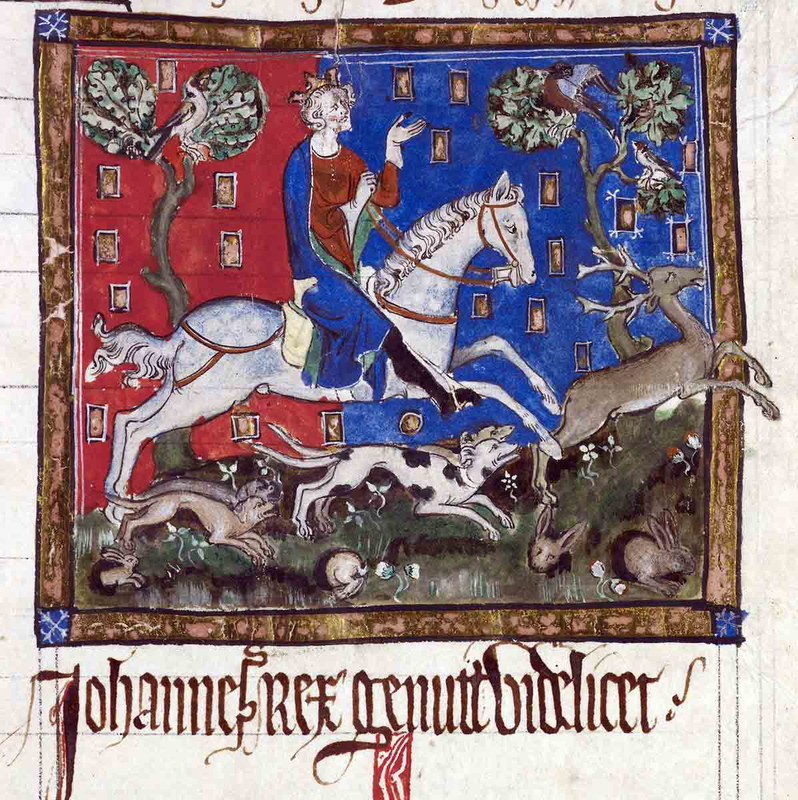

5. “Caught Red-Handed”

If someone is “caught red-handed,” they’re caught in the act.

The phrase goes back to 15th-century Scottish law, which required a person to be caught either in the act, or with fresh blood still on their hands, to be convicted of certain crimes—especially killing livestock or poaching. Blood on your hands was literally the evidence.

The expression survived and broadened in meaning, but that original “red” was all too real.

6. “Drawn and Quartered”

Today, “they’ll have me drawn and quartered” is an exaggerated way to say you’re in big trouble.

In medieval and early modern times, it referred to a very real and very horrific method of execution: being hanged, drawn, and quartered. The condemned was:

- Hanged, then cut down before death

- Mutilated (genitals removed, bowels taken out and burned)

- Beheaded

- Body divided into four parts and displayed as a warning

The Scottish patriot William Wallace suffered this fate in 1305. The phrase’s survival in casual speech is a reminder of just how brutal punishment once was.

7. “Sink or Swim”

We say “sink or swim” when someone is thrown into a tough situation and has to succeed or fail on their own.

Its roots lie in trial by ordeal, a medieval method of letting God “decide” guilt or innocence. In some water ordeals, the belief went:

- The innocent would sink into the water

- The guilty would float, rejected by the “baptismal” waters

In other words, if you floated, you might have “passed” the test—but it meant death in the legal sense. Today, the phrase has softened into metaphor, but it began in life-or-death superstition.

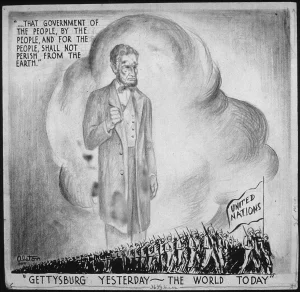

8. “No Man’s Land”

We associate “no man’s land” with the deadly ground between trench lines in World War I.

But the phrase is much older. It appears in the Domesday Book of the 11th century as “nanesmanesland”—literally “no man’s land”—to describe desolate, uninhabited areas like waste ground or garbage dumps outside towns.

Over time, it kept the sense of dangerous, ownerless, or contested space, whether on a battlefield or in everyday speech.

9. “By My Troth”

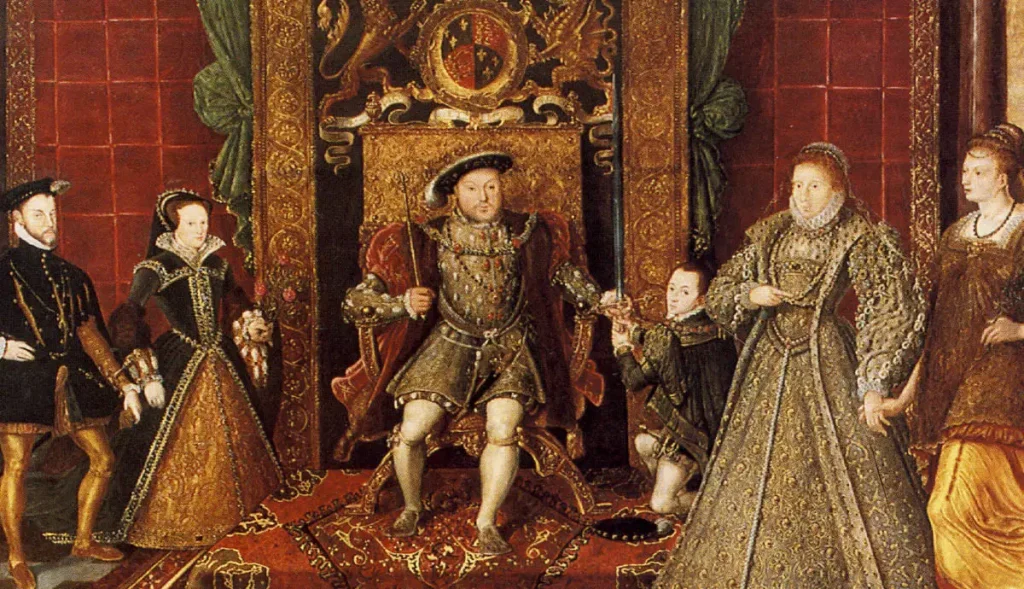

“By my troth” sounds quaintly Shakespearean today, but it was once a common oath.

In Middle English, “troth” meant “truth” or “faith.” Saying “by my troth” was like saying “by my word” or “I swear this is true.” It appears frequently in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in the 14th century and survived into Elizabethan drama, where Shakespeare’s characters use it as a standard everyday swear.

10. “Memento Mori”

“Memento mori” is still used as a reminder of mortality: “remember that you must die.”

In the Middle Ages, this Latin phrase was a staple of sermons, religious writings, and devotional art. Skulls, hourglasses, and grim allegories were meant to remind believers that life is short, death is certain, and they should live righteously.

We still use the phrase today, often with a more reflective, philosophical tone—but its origins are deeply rooted in medieval religious culture.

11. “By God’s Bones”

“By God’s bones!” sounds like something from a fantasy novel, but it was a real medieval curse.

People swore “by God’s bones,” “by God’s eyes,” “by God’s nails,” and so on, referring to the physical body of Christ. These were considered blasphemous oaths, breaking the commandment against taking the Lord’s name in vain.

In a world where oaths were deadly serious—communities depended on promises and sworn agreements—using sacred imagery this way wasn’t just rude; it was deeply offensive.

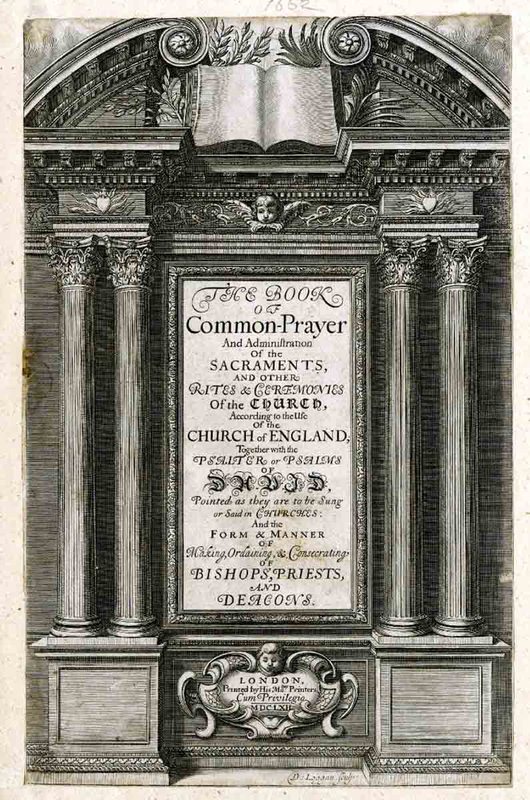

12. “The World, the Flesh, and the Devil”

“The world, the flesh, and the devil” is a classic Christian phrase naming the three great enemies of the soul:

- The world – external temptations and pressures

- The flesh – internal desires and weaknesses

- The devil – spiritual evil

In the Middle Ages, this trio appeared constantly in sermons, theology, and spiritual writings, becoming a well-known idiom. It was still standard enough to appear in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, and it lingers today as a shorthand for all the forces that drag us away from the good.

13. “Blood Is Thicker Than Water”

We use “blood is thicker than water” to mean family bonds are stronger than other ties.

The phrase can be traced back to 13th-century Germany, where it seems to have carried the idea that blood ties could be weakened or “diluted,” possibly in contrast with baptismal water. By the 15th century in England, it had taken on a clearer contrast: water leaves no mark, but blood stains and clings, making it a vivid image for relationships that cannot be easily erased.

The modern meaning—family first—grew out of this association with blood as something lasting and hard to wash away.

14. “One Bad Apple”

We often shorten it to “one bad apple,” but the original proverb is “one bad apple spoils the whole barrel.”

The saying is literal: if you stored apples in barrels and one started to rot, it could quickly spread decay to the others. Medieval and early modern people knew this from daily life.

Writers turned this into a moral lesson. Geoffrey Chaucer, in The Cook’s Tale, uses the image of a “bad apple” to describe a person whose behavior corrupts those around them. Today, it’s still a warning that one person’s negativity (or wrongdoing) can infect a whole group.

15. “More Irish Than the Irish”

This phrase comes from medieval Ireland and the Norman conquest.

From the 12th century onward, Anglo-Norman nobles invaded and settled in Ireland. They formed a ruling class—but many also enthusiastically adopted Irish language, dress, and customs. To English authorities, this was alarming: the conquerors were becoming too much like the conquered.

By 1366, the Statutes of Kilkenny tried to stop this cultural blending by banning certain Irish customs for Anglo-Normans. Those who ignored the rules were described as becoming “more Irish than the Irish” themselves.

Today, we still use the phrase for outsiders who embrace a local culture even more passionately than the locals do.

Language carries history in its pockets. The next time you say someone was “caught red-handed,” or that it’s “sink or swim,” or joke you’ll be “drawn and quartered,” remember: you’re speaking with the ghosts of medieval markets, courts, and churches still echoing in your words.