On a windless Egyptian night, Julius Caesar watched the Nile turn to ink. Overhead, Sirius burned like a pinprick of fire—ancient Egypt’s timekeeper—while, far away in Rome, the calendar bled days and lost its grip on the seasons. Grain fleets left at the wrong moment. Festivals slipped from their sacred moorings. Magistrates stretched or shrank the year to suit their politics. Time itself felt… negotiable.

Caesar, fresh from civil war and newly powerful enough to reshape the world, resolved to do something few had dared: he would rewrite the very fabric of the year. The reform he launched in 45 BCE—the Julian calendar—did more than tidy Rome’s paperwork. It synchronized harvests, sanctified holidays, disciplined politics, and set a rhythm that would pulse through empires, monasteries, observatories, and modern life for two millennia. This is the story of how one man changed time—and why his calendar still echoes in our days.

Before the Reform

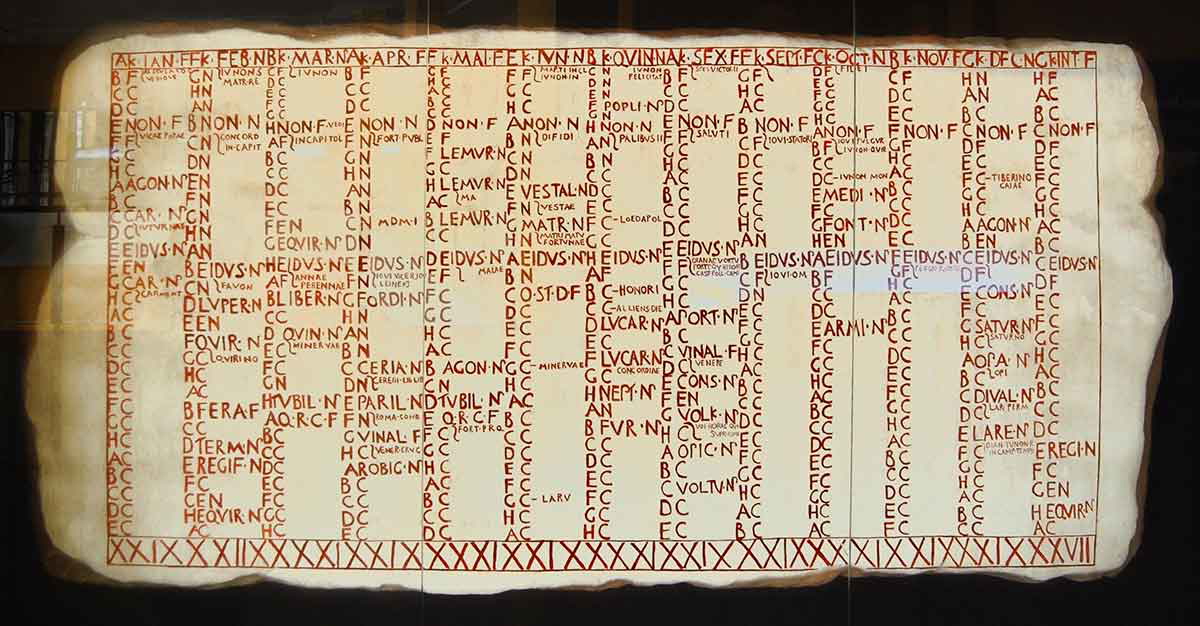

The earliest Roman year was a peculiar creature: ten months, roughly 304 days, stacked against winter like a flimsy fence against a storm. Eventually, under the legendary king Numa Pompilius, the Romans attached two new months to the front—Ianuarius and Februarius—and embraced a twelve-month lunar cycle. It was clever enough in an age of plows and auguries, but the moon runs faster than the sun; twelve lunar months total only about 354–355 days. That shortfall—ten or eleven days each year—meant the calendar drifted steadily away from the seasons.

The Romans developed a workaround: an extra, occasional month, Mercedonius (or Intercalaris), quietly slipped in after February to patch the gap. In theory, the pontiffs (Rome’s priestly timekeepers) would intercalate with restraint and precision. In practice, the calendar became a political instrument. To extend a friend’s tenure or abbreviate an enemy’s, powerful patrons nudged priests to add or withhold days. By the turbulent final decades of the Republic—civil war, rival strongmen, failing norms—the Roman calendar lagged the sun by roughly three months. Planting dates went awry, legal deadlines blurred, and public festivals toppled out of season. Time was a battlefield—and ordinary Romans paid the cost.

Caesar in Egypt

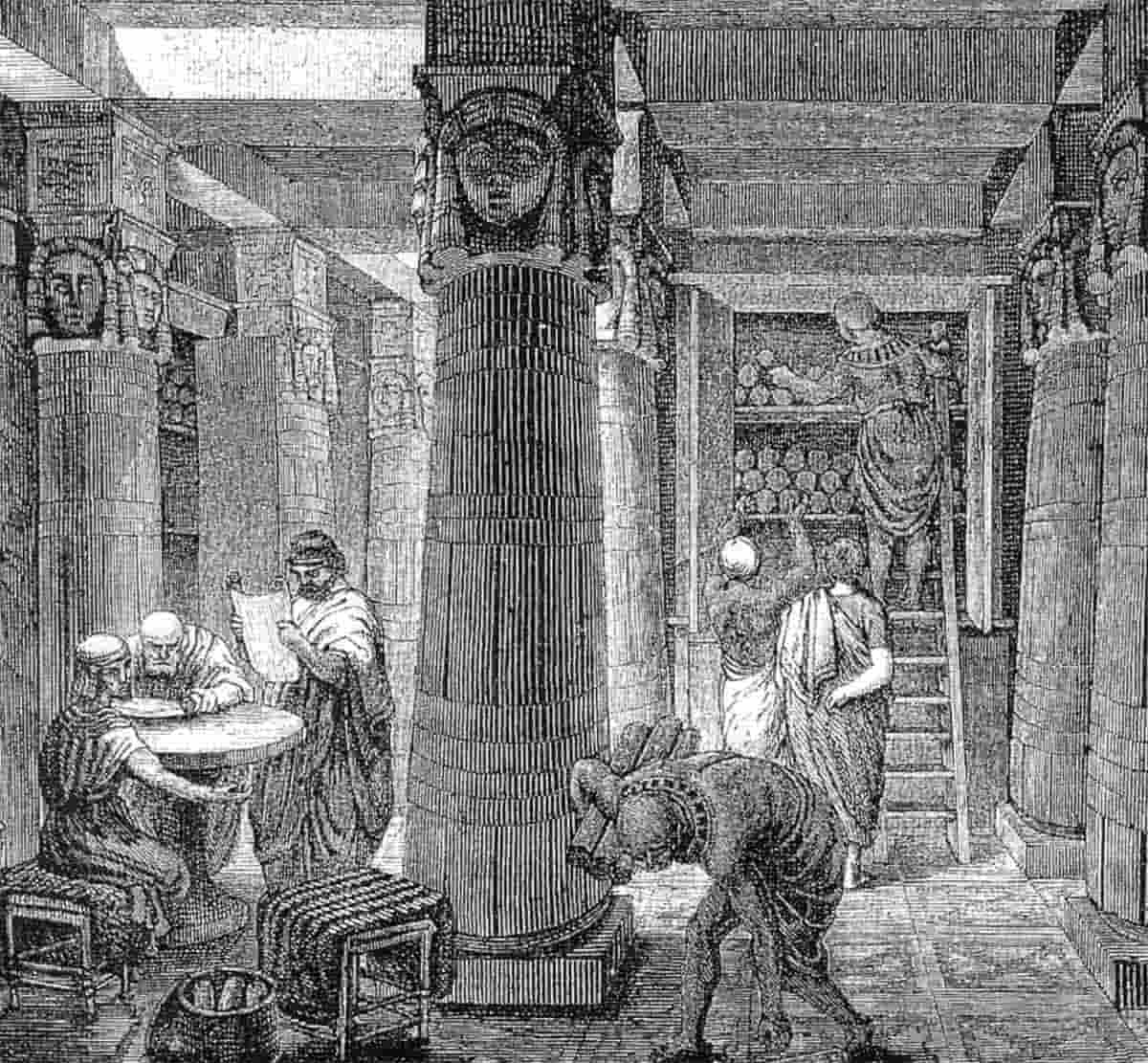

After defeating Pompey’s forces at Pharsalus in 48 BCE, Caesar followed the trail east and stepped into the intellectual furnace of Alexandria. There, under skies that scholars had read for centuries, he met a different way of counting. The Egyptians lived by a solar year—steadier, calmer, truer to the seasons—and their astronomers had refined it with remarkable accuracy.

Among them was Sosigenes of Alexandria, a Greek astronomer whose counsel would change Rome. Under Caesar’s authority as pontifex maximus and, soon, dictator perpetuo, the two crafted a reform that was both elegant and enforceable. Where past systems had asked priests to make judgment calls, Caesar and Sosigenes designed a calendar that would mostly run itself.

Resetting the Sun

Before the new machine could hum, the old one had to be reset. The Roman year had drifted so far from the seasons that it could no longer be gently corrected. In 46 BCE—a year Romans later called the annus confusionis, the Year of Confusion—Caesar extended the calendar dramatically to realign civic time with the sun’s cycle. Only then, in 45 BCE, did the new year dawn on a corrected sky.

What Caesar unveiled was simple enough to teach, robust enough to endure:

- A solar year fixed at 365 days, with an additional leap day added every fourth year.

- Months standardized to 30 or 31 days, with February bearing the exception and receiving the leap day.

- The civic year anchored to a consistent start in January, giving administration and law a predictable cadence.

- The elimination of the arbitrary intercalary month, stripping priests and politicians of their favorite instrument for manipulating time.

In one stroke, the Roman calendar ceased to be an improvisation and became an institution.

Naming Time

Calendars do more than measure; they memorialize. The seventh month—Quintilis, literally “the fifth” from older reckonings—was rechristened Iulius (July) in 44 BCE to honor Caesar himself. Later, Sextilis became Augustus (August) in tribute to the first emperor. Echoes of the older numbering survive in the modern September (seventh), October (eighth), November (ninth), and December (tenth)—spare ribs of an ancient skeleton carried beneath today’s flesh of names.

How the Julian Calendar Worked (and Why It Worked)

The genius of the Julian system lies in its balance of astronomy and administration. By pegging the year to the sun and distributing days evenly across months, Caesar’s reform delivered:

- Seasonal Stability

Farmers could sow and reap by trustworthy dates; military campaigns could plan logistical windows; grain fleets could catch the right winds. Time stopped slipping underfoot. - Civic Clarity

Courts, assemblies, and markets beat to a single, predictable rhythm. Contracts matured on schedule; magistracies ran their course. The state functioned more like a state—and less like a storm. - Religious Regularity

Festivals such as Saturnalia or Lupercalia acquired fixed homes in the year, deepening their emotional gravity. No longer did priests need to “announce” the calendar; the calendar announced itself. - Imperial Cohesion

As Roman power spread, so too did Caesar’s calendar—a silent empire of days overlaying the empire of legions. Provinces could coordinate taxation, censuses, and trade on a common clock. Time became Rome’s soft infrastructure.

The reform even carried a built-in humility: a leap day every four years conceded that the sun won’t pack itself neatly into whole numbers. That concession made the system self-correcting and, crucially, low-maintenance.

The Human Side of a Technical Fix

Try to imagine living through the shift. You’re a vintner in Latium who’s misread the grapes three harvests running. You’re a magistrate whose term has yo-yoed because factional priests stretched a year like taffy. You’re a priest who, after Caesar, no longer flips a divine switch to add a month. Overnight, the empire says: here is the year—solid, repeatable, indifferent to intrigue. The sky you’ve always seen is now the clock you can trust.

For many Romans, that must have felt like a weight lifting. For others—those whose influence relied on manipulating time—it was a quiet revolution.

From Empire to Christendom

The Julian calendar did not vanish when the Republic did. It threaded the Imperial centuries, survived the crises of the third century, and slipped across the threshold of Constantine’s world, where the empire began to call itself Christian. In time, bishops and monks layered the calendar with a sanctoral cycle—a daily litany of saints—while the great feasts, fixed and movable, mapped salvation history onto Caesar’s grid.

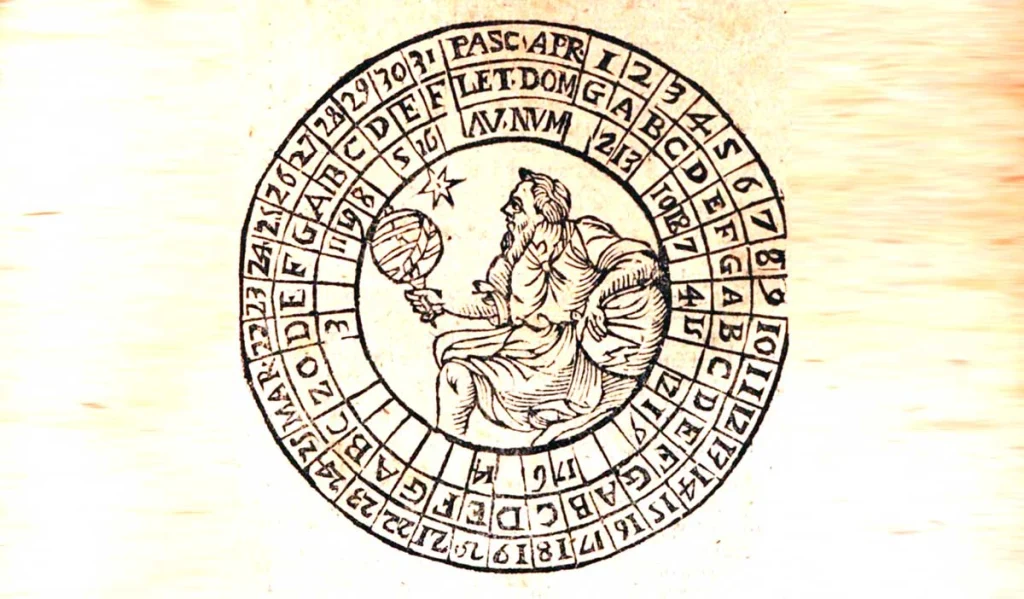

In monasteries, the study of time grew exacting. Scholars labored over the computus—the tricky mathematics of determining Easter, whose date depends on the spring equinox and the lunar cycle. Scriptoriums hummed not only with scripture but with tables, epacts, and cycles: mathematics braided into devotion.

Across medieval Europe, the Julian calendar provided a shared architecture even as regions exercised local flavor. New Year’s Day might fall on March 25 (the Annunciation) in England, December 25 in parts of Germany, or March 1 in Venice. Markets and fairs kept local saints’ days; harvest festivals hugged regional climates. Yet beneath these variations, the months marched in step. You could ride from Canterbury to Cologne and never lose the thread of the year.

A Small Error, a Big Drift

No calendar is perfect; the sun is a stubborn clock. The Julian year of 365.25 days runs slightly long. The real tropical year is about 11 minutes shorter. That sliver seems trivial—until the centuries stack. Over time, the drift nudged the calendar’s spring equinox earlier and earlier, making the calculation of Easter increasingly awkward. By the 1500s, the discrepancy had swelled to ten days.

The problem was not theological posturing but astronomical housekeeping. If the church wished to celebrate Easter in the proper season and keep the feasts tethered to the sky, the calendar needed recalibration.

The Gregorian Fix

Enter Pope Gregory XIII, who convened experts—most famously Aloysius Lilius and Christopher Clavius—to refine Caesar’s mechanism. Their solution, implemented in 1582, was at once bold and surgical:

- Skip ten days to realign the equinox (in adopting regions, October 4 was followed by October 15).

- Fine-tune leap years: century years (e.g., 1700, 1800, 1900) would not be leap years unless divisible by 400 (so 1600 and 2000 are leap years; 1700, 1800, 1900 are not).

The effect was dramatic: the Gregorian calendar’s error dropped to about one day every 3,300 years—a tidy improvement over the Julian rhythm of roughly one day every 128 years. Adoption rippled outward unevenly—Catholic realms first, Protestant and Orthodox lands later—but eventually the Gregorian scheme became the world’s civil standard. Still, the bones of Caesar’s design remain visible in the names, lengths, and sequence of our months.

The Julian Calendar Today

Though replaced in civic life, the Julian calendar continues to beat in religious and cultural contexts:

- Eastern Orthodox churches (and some Eastern Catholic communities) retain Julian reckoning for many feasts, which is why Orthodox Christmas often falls on January 7 (Gregorian). This “dual dating” turns the global winter into a season of twin Nativity lights.

- Historians and genealogists constantly translate between systems. Records from Rome to Renaissance, from medieval charters to Muscovite decrees, speak Julian dates; to pin events on a modern timeline, scholars “convert” Caesar’s time into Gregory’s.

- Astronomers use the Julian Day Number—a continuous count of days beginning in 4713 BCE—to timestamp celestial events with mathematical clarity. The name honors the tradition more than the exact civil calendar, but the lineage is unmistakable.

- Cultural survivals persist beyond Europe. The Berber agricultural calendar and Ethiopian (and Eritrean) Christian practices preserve rhythms derived from Julian principles, proof that Caesarian time found homes far from the Tiber.

More Stories

What Changed When Caesar Changed Time

It’s tempting to see a calendar as a dry grid of boxes—appointments, birthdays, deadlines. But Caesar’s reform rippled through deeper waters:

- Power and Accountability

By outlawing opportunistic intercalation, the Julian calendar tamed a subtle form of political manipulation. Time ceased to be a lever in the hands of the few and became a shared contract among the many. - Economy and Empire

With predictable seasons and synchronized schedules, grain moved, armies marched, taxes were assessed, and markets stabilized. An empire as vast as Rome required an invisible infrastructure; the calendar was one of its strongest beams. - Memory and Meaning

Fixing festivals to steadfast dates allowed traditions to take root. Saturnalia at winter’s edge, the rites of spring, the harvest’s gratitude—their repetition carved grooves of meaning into communal life. - Science and Stewardship

The leap-year principle taught generations that the natural world resists tidy arithmetic—and that good systems anticipate small mismatches with gentle corrections. It was a lesson in humility disguised as math.

The Narrative Arc of a Year

Think of the Julian reform as a story with a classical shape:

- Beginning: A broken calendar, bent to faction and fortune, drifts away from the sun.

- Rising Action: Caesar, standing amid Egypt’s wisdom and Rome’s needs, assembles the tools to fix it.

- Climax: The Year of Confusion stretches and snaps the old cords; the Julian year clicks into place in 45 BCE—a new drumbeat for the empire.

- Resolution: Centuries of stability follow. Monks lace prayer over its bones. Merchants and magistrates walk to its metronome.

- Denouement: Gregory trims the mechanism without breaking its frame. The world adopts the refinement—but the silhouette of Caesar’s calendar remains.

In that arc lies a paradox: the most profound revolutions sometimes feel, in daily life, like a sigh of relief. The sun rises, the month advances, and fields keep their promises. Stability is felt most keenly when it returns after chaos.

A Quiet Monument

Caesar left monuments in marble, campaigns etched into maps, and a biography that still startles with ambition. Yet the most enduring monument might be the calendar in your kitchen and the one humming in your phone—months named for men and numbers, weeks that parcel labor and rest, a leap day that visits every four years like a mechanical angel reminding us that nature refuses perfect counting.

You can count the distance from a vineyard in Latium to a space telescope at Lagrange not only in miles and centuries but in organized days—a lineage of timekeeping that begins with a Roman general staring at Egyptian stars and deciding the world deserved a better year.

Julius Caesar did not conquer the sun. He did something more human and more lasting: he listened to it, then taught Rome—and eventually the planet—how to keep time by its light.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Petra: The Rose-Red City and the Scented Road

Nero: Madman or Misunderstood?

The Acropolis of Ancient Greece

Andrew Jackson: A Legacy of Native American Oppression

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

What Is the Philosophy of Film?

Liberation Theology and the Shockwaves Through Latin America

A Surprising, Long History of Veterinary Medicine

5 Legendary Kings Who Built Thailand: From Sukhothai to the Chakri Dynasty

Julius Caesar and the Danger of Punishment Without Due Process

When Achilles Met Penthesilea

Livia Augusta—First Roman Empress