We inherit our taboos like we inherit our language: invisibly, by living inside them. In the modern West, the “incest taboo” feels absolute—universally illegal for siblings to wed and widely condemned as immoral and unnatural. Yet step back four thousand years to the banks of the Nile, and that certainty dissolves like silt in floodwater. Here, the most exalted unions were sometimes between brother and sister. They were not whispered secrets—they were coronations, liturgies, a choreography of power cast against the horizon of eternity.

To understand why Egypt’s elites embraced what later cultures would recoil from, we must enter a world where religion shaped politics, where cosmic balance—Ma’at—was a daily labor, and where the pharaoh was not merely a king but the living hinge between heaven and earth. In that world, a royal wedding could echo the first marriage in the cosmos: the sacred union of Isis and Osiris. And if the gods themselves were siblings as well as spouses, why shouldn’t their children on earth do the same?

What follows is the story of adelphogamy—brother–sister marriage—in Ancient Egypt: how it emerged, why it peaked, where it became perilous, and what it meant to those who lived it.

The sacred script

Many ancient mythologies imagine the first couples as siblings by necessity—after all, when the world is young, partners are few. The Egyptians went further. Their hieros gamos, or sacred marriage, wasn’t just cosmology; it was a template. Pairs like Shu and Tefnut (air and moisture) or Geb and Nut (earth and sky) embodied a cosmic duality that required union to keep creation breathing.

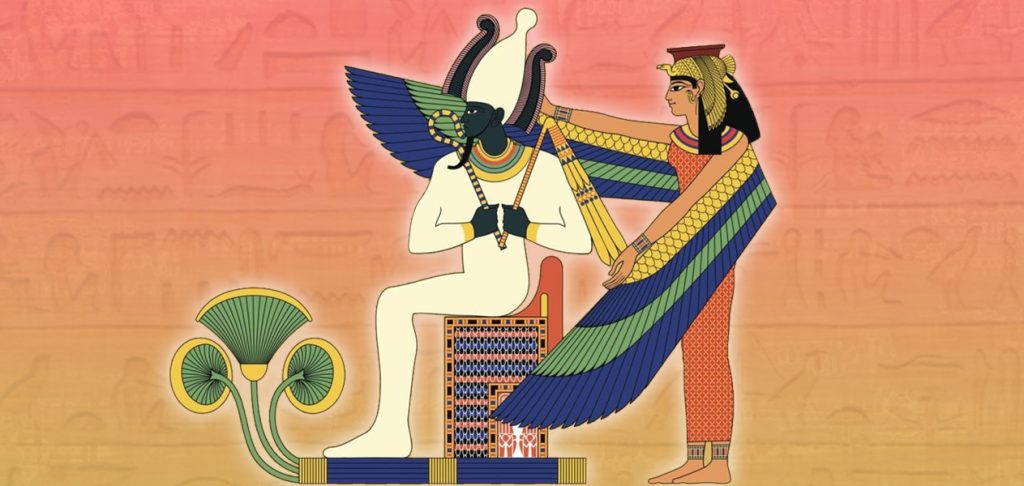

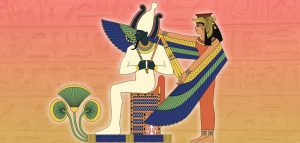

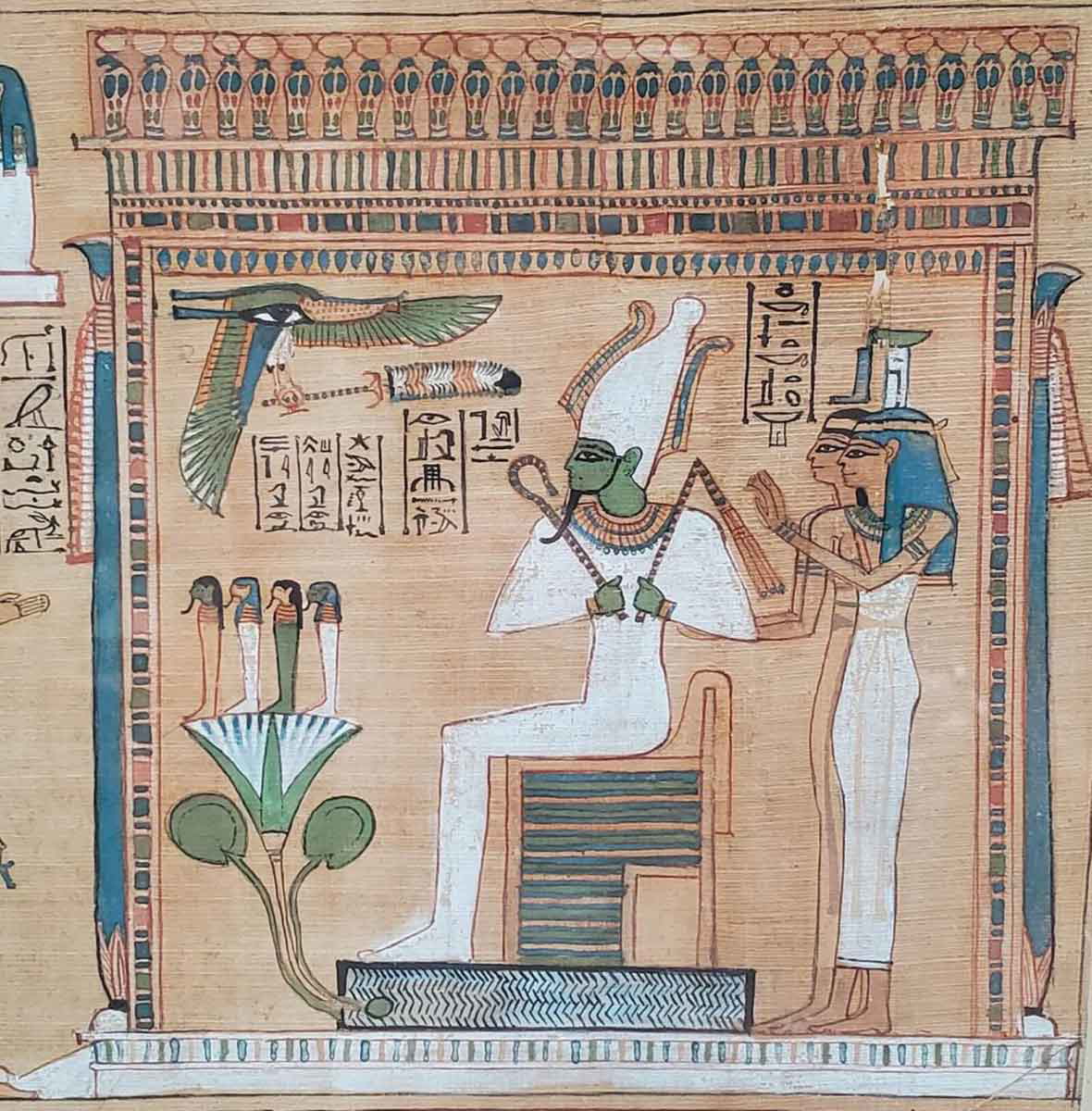

Above all stood Isis and Osiris. He, the god of the Nile’s bounty and the fertility of fields; she, goddess of magic, motherhood, and protection. When Osiris was murdered by his jealous brother Set and dismembered across the land, Isis became Egypt’s tireless pilgrim, gathering her husband’s scattered pieces, reanimating him, and conceiving their son Horus—the very essence of kingship. Love, loss, magic, resurrection: their story isn’t an explanation for incest; it is a proclamation that wholeness—even after rupture—comes from the union of matched forces.

On earth, Pharaohs read this myth as mandate. To mirror divine order, they often married sisters or half-sisters. In doing so, a king closed the circle: the royal bloodline looped back on itself, preserving divinity, legitimacy, and the fragile balance of Ma’at.

Love rarely ruled

Across most ancient societies, marriage was never primarily for romance. It was a lever: for economic consolidation, political alliance, and dynastic survival. Egypt’s upper classes were no exception. Sibling marriage offered two potent assurances:

- Purity of the royal line. If the pharaoh’s blood was divine, then a union with his sister—herself a vessel of that sanctity—would keep the god-stuff undiluted.

- Consolidation of wealth and power. Property passed through daughters as well as sons. Marrying a sister kept estates intact, prevented rival families’ claims, and stabilized succession.

To modern readers this may feel cold, even chilling. But to Egyptians, the calculus was sacred and practical at once. The taboo we presume simply did not exist in the same way.

Old Kingdom origins

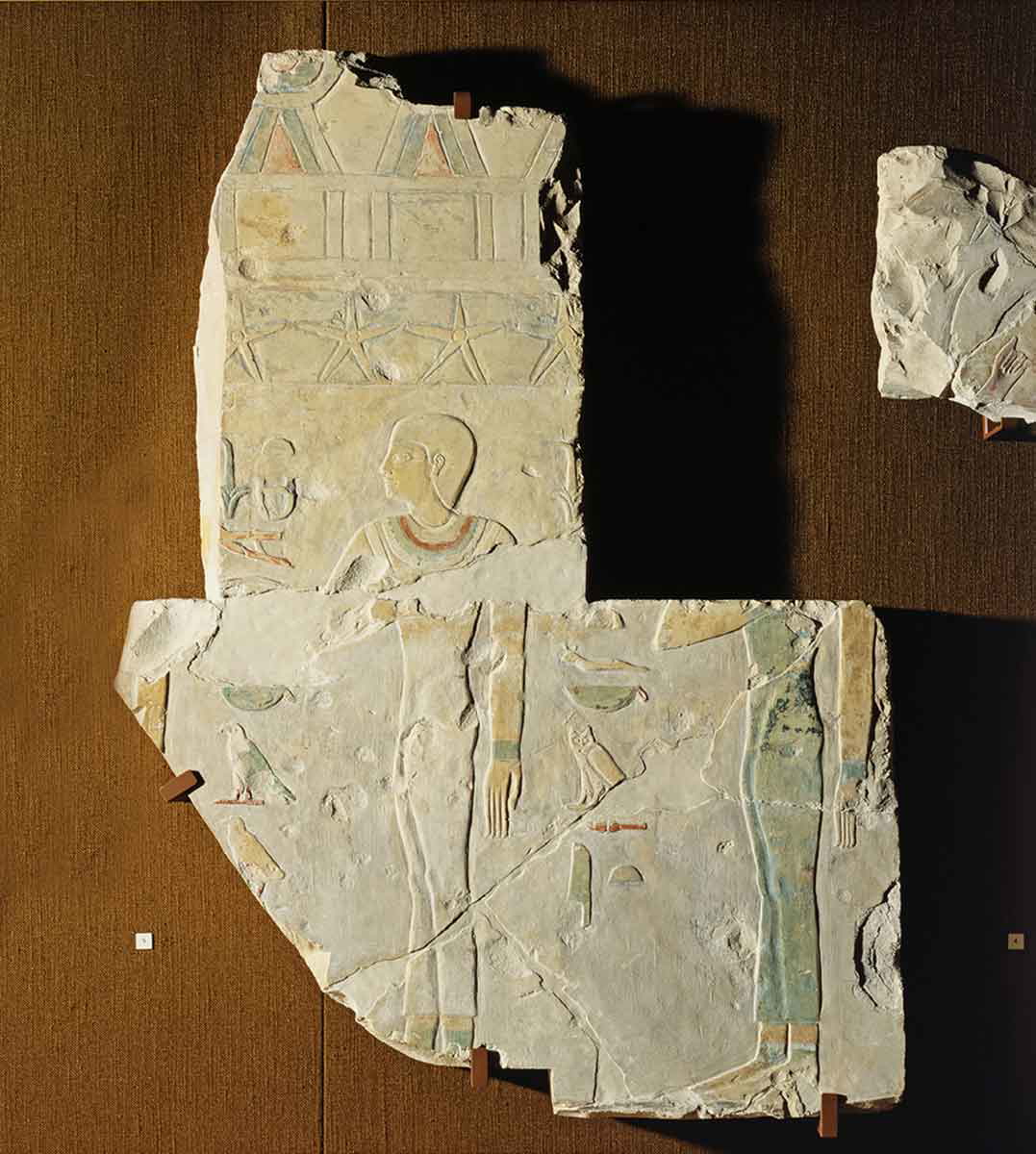

The Old Kingdom—the age of the pyramids—also gives us some of the earliest clear proofs of royal consanguinity. While whispers reach back to the 1st Dynasty (the likely sister-wife Merneith of Pharaoh Djet), records coalesce under the 4th and 6th Dynasties:

- Khufu, the architect of the Great Pyramid, may have married his half-sister Meritites I, daughter of Sneferu.

- Khafre, builder of the second Giza pyramid and the Great Sphinx, wed his niece Meresankh III; another wife, Khamerernebty I, was possibly a half-sister and mother of Menkaure.

- Menkaure then married his full sister Khamerernebty II—a marriage that symbolically sealed the pyramid age’s insistence on bloodline continuity.

- In the 6th Dynasty, the long-reigning Pepi II married within his family (including his sister Ankhesenpepi III and close relatives Neith and Iput II). Neith bore his successor Merenre II.

In this period, as the royal state consolidated its authority, marital strategy reinforced central power. As divine kin mated in heaven, so royal kin intermarried on earth.

The Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom often hides in the shadow of Egypt’s more flamboyant eras, but cousin to cousin and sibling to sibling bonds persisted:

- Mentuhotep II, the dynasty’s founder, counted his sister Neferu among his chief consorts, though no children from the union are attested.

- About a century and a half later, Senusret II likely married multiple sisters; Khenemetneferhedjet I was mother to Senusret III, one of the age’s titans.

- The first definitively attested female pharaoh, Sobekneferu, who succeeded Amenemhat IV, may also have been his sister.

A few records hint that commoners of high rank—a vizier here, a priest there—sometimes married sisters during this era. Egyptologists debate these claims. Were they true sibling unions, or simply couples whose fathers happened to share a common name? Either way, the consensus remains: adelphogamy was a royal prerogative, not a widespread social norm.

The New Kingdom

Enter the New Kingdom, Egypt’s golden blaze—wasp-waisted statues and sun-splashed temples, thundering chariots and imperial reach. Here, sibling unions became customary across the 18th Dynasty:

- From Ahmose I and Amenhotep I through Thutmose I–IV, pharaohs frequently married sisters or half-sisters.

- The celebrated pairing of Thutmose II and Hatshepsut—both of whom ruled as pharaoh—produced the princess Neferure. Scholars debate whether Neferure later married her half-brother Thutmose III, but the tradition would not have blinked at it.

The Amarna labyrinth

With Akhenaten—the heretic king who elevated Aten, the sun disc—the family tree becomes a maze. He married Nefertiti, long thought foreign but now considered an Egyptian noble, possibly a cousin. Some argue they were first cousins; others propose a closer tie. Their daughter Meritaten married the shadow-king Smenkhkare, whose identity flickers in the record: Akhenaten’s son? His younger brother? Or—astonishingly—Nefertiti herself ruling as co-king under another name? If Smenkhkare was a brother or an avatar of Nefertiti, Meritaten’s marriage was certainly intra-familial—possibly to brother, uncle, mother…or to herself if Meritaten and Smenkhkare were one and the same in different guises.

Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun

The best-known chapter belongs to Tutankhamun, who married his sister Ankhesenamun. Genetic evidence suggests Nefertiti was certainly Ankhesenamun’s mother and may also have been Tutankhamun’s, making the pair full siblings. Their union tried to extend the royal line but ended in heartbreak: two miscarriages, and with them, the effective end of the 18th Dynasty’s pure-blood lineage. Tut’s fragile health—likely compounded by generations of inbreeding—echoes the biological risks encoded in dynastic policy.

Beyond siblings

Even by New Kingdom standards, a few marriages shocked modern sensibilities. Amenhotep III likely elevated his daughters Sitamun and Iset as Great Royal Wives. The mighty Rameses II—builder, warrior, and perhaps the last of the truly colossal pharaohs—married three daughters: Bintanath, Meritamun, and Nebettawy. Bintanath bore him a daughter. These unions were not the norm, but they were credible, ceremonial, and politically legible.

Murder in the palace

Dynastic intimacy could turn lethal. Rameses III, sometimes styled Egypt’s “last great pharaoh,” was murdered in a palace conspiracy stoked by rivalry between wives. The assassin’s motive? To vault another son to the throne over Tyti, the king’s sister-wife and mother of the heir Rameses IV. In the end, the usurper prince and conspirators died, and Egypt’s royal house learned—again—that family could be the most dangerous faction of all.

Later dynasties

In the Third Intermediate Period, adelphogamy proved a tool for legitimacy. Psusennes I of the 21st Dynasty married his half-sister Mutnedjmet. The match knit together priestly and royal claims: both were children of the powerful High Priest Pinedjem, who had earlier declared himself pharaoh, and Mutnedjmet’s mother descended from Rameses XI. The wedding stitched the new regime to the storied Ramesside line—politics in the language of kinship.

The Ptolemies

When Alexander the Great died, Egypt became the fief of his general Ptolemy I. The new Greek rulers took up Egyptian trappings with gusto, including sibling marriage—now named with Greek frankness: adelphogamy. If the practice among earlier pharaohs felt ceremonial, under the Ptolemies it often turned flamboyantly theatrical.

- Ptolemy II Philadelphos (“sibling-lover”) married his full sister Arsinoe II—a royal headline that did exactly what it was meant to do: declare continuity with Egyptian tradition and the god-kings of old.

- Two generations later, Arsinoe III bore Ptolemy V by her brother Ptolemy IV.

Then the stage darkened into family tragedy:

- Cleopatra II married her brother Ptolemy VI (four children), and after his death, their brother Ptolemy VIII, who later also married his niece/stepdaughter Cleopatra III—all while Cleopatra II still reigned.

- Cleopatra III produced five children for Ptolemy VIII, outmaneuvered her own mother in a bruising power struggle, elevated her favored son Ptolemy X, and was eventually murdered by him.

- Ptolemy IX, pushed off and on the throne, may be the era’s consanguinity champion. He married his sister Cleopatra IV (apparently for love), then—under his mother’s pressure—divorced her to marry another sister Cleopatra V Selene. Later, he elevated his daughter Berenice III as co-ruler; whether the arrangement was formal marriage or political co-regency, the message was the same: power stayed in the family loop.

The curtain falls with Cleopatra VII—the Cleopatra—born of a brother–sister union (Ptolemy XII and possibly Cleopatra V/VI). She in turn married both her younger brothers, Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV, shedding each when expedient. With Julius Caesar and later Mark Antony, Cleopatra tried to pivot Egypt’s fate. Rome had the final word. After her death, Augustus ended the dynasty and, with Roman disdain, closed the book on the Ptolemaic experiment in spectacle, sovereignty, and sibling marriage.

Why did brother–sister marriage matter so much?

If sibling unions were meant to safeguard divinity and property, they also served subtler purposes in the Egyptian imagination.

1) Divinity travels through women

Some Egyptologists argue that while kingship passed from father to son, divine legitimacy—the “current” of sacred authority—flowed through the royal daughter. If so, a prince’s marriage to his sister wasn’t optional; it was the charging cable that lit his kingship. The queen’s statues often show her grasping the pharaoh’s arm—not as decoration, but as conduit and guide, the earthly Isis to his Osiris.

2) Ceremony versus fertility

A tidy theory claims the sister was a ceremonial Great Royal Wife, while concubines and non-royal wives supplied heirs. The evidence, however, refuses to be tidy. Plenty of sister-wives bore children; plenty of outsiders became mothers of kings. The truth is likely pragmatic: pharaohs married for ritual, politics, and personal preference, and no one told a living god whom he could or could not wed.

3) Property kept whole

Egyptian daughters could inherit, and estates were easier to keep intact when property didn’t bleed into rival houses. A brother marrying his sister kept land, titles, and treasures concentrated—a quietly compelling reason beneath the theological thunder.

Health, heredity, and hindsight

Genetics was not a word in pharaonic Egypt, and yet its realities stalked the palace halls. Multi-generational inbreeding carries risk: miscarriages, infant mortality, congenital conditions. Tutankhamun’s short, fragile life and the couple’s tragic pregnancies look—through modern eyes—like the biological bill coming due. But we must resist reading backward with condemnation. Egyptians did not know what we know, and they often downplayed or ritually concealed imperfections in the royal body. The pharaoh was a living god; gods are whole by definition.

The modern mirror

It’s tempting to judge. Today, even first-cousin marriage—legal in fewer than half of U.S. states—is controversial; sibling unions are criminalized across the West. Meanwhile, relationships once shunned for other reasons have found acceptance. Cultures change. Taboos move. If anything, the heightened modern repugnance toward incest shows how deeply our societies anchor morality in biology and consent, not cosmology.

Yet to understand the Egyptians, we must stand inside their world. In a universe held together by Ma’at, where kings had to be both human and divine, where Isis was every queen and Osiris every king, brother–sister marriage was less a violation than a vow—a pledge to keep the sky mated to the earth, the river faithful to its banks, and the throne inheriting its own sanctity.