The story of Ottoman warfare begins on a sea of grass and ends beneath the thunder of bronze. It is a tale of horsehair bowstrings and matchlock sparks, of raiders who became rulers, and of an empire that learned—sometimes faster than its rivals, sometimes not fast enough—to trade the speed of the steppe for the discipline of a barracks and the recoil of a gun. From the wind-whipped plains of Central Asia to the stone ramparts of Constantinople and the stormy narrows of the Mediterranean, the Ottomans reshaped their art of war as their world expanded. What follows is the arc of that transformation: how a nomad’s toolkit—bow, arrow, sword, horse—grew into the arsenal of a gunpowder empire.

Riders of the Steppe

Before the domes and minarets, before the chancelleries and treasuries, there was the saddle. The early Ottomans, a Turkmen band in western Anatolia in the early 1300s, lived and fought according to the physics of the open range. Osman, the pastoralist chieftain whose name the dynasty carries, inherited a tradition familiar across the Central Asian steppe: warfare as a dance of speed and space. The bow was king; the horse was breath and bone.

Their signature fighters were horse archers—light, lethal, and elusive. They moved like weather fronts, appearing at the enemy’s flank in a blur of hooves, loosing arrows at full gallop, then vanishing before a counterstrike could organize. These raids were economical as much as tactical: a pastoral life doesn’t yield much in metal or grain, so war supplemented what herds could not. From the Balkans to the Aegean littoral, such strikes shook markets and garrisons, softened borders, and opened doors to settlement.

But raiding alone cannot hold territory. As the Ottomans pushed into sedentary, often Christian lands, they learned that to conquer towns you must stop long enough to govern them. Orhan, Osman’s son, began that pivot. In his reign (r. 1323–1362), the principality experimented with a modest standing force—the yaya (infantry) and müsellem (cavalry)—paid soldiers who fought not for plunder but for a salary, sometimes compensated with land. These units brought order where raiding brought chaos, but they brought new problems, too: cost, local power bases, and the risk that a soldier loyal to his fief would think less of the sultan far away.

The Ottomans needed permanence without provincial barons, discipline without divided loyalties. Their solution would become one of the most distinctive institutions in early modern warfare.

The Janissary Revolution

Out of conquest and law came a corps unlike anything Europe had seen: the Janissaries. The logic was brutal and brilliant. Islamic legal custom entitled victors to a share of war spoils, and over time the Ottomans refined that into a system—the devshirme—that levied human tribute from Christian populations in the Balkans. Boys were taken into the sultan’s service, converted to Islam, and educated with a singular purpose: to be instruments of the state.

Some of these recruits entered the Enderun, the palace school that groomed administrators and statesmen, men who would move ledgers, embassies, and armies. Others formed the Janissary corps, the kapıkulu, “slaves of the Porte,” who owed allegiance not to family or tribe but to the sultan himself. They were uniformed, barracked, trained, and paid with regularity unusual for the age. They marched to the mehter, a military band whose pounding kettledrums and piercing zurnas signaled cadence and courage. Organized into battalions known as ortas, they developed specialties—personal guard, line infantry, later even musketry—that set a template for the modern, professional standing army.

This was more than an administrative tweak. It was a revolution in trust. The raiding Turkmen who had propelled early Ottoman expansion answered to clan and custom; the Janissaries answered to command. In an empire that straddled cultures and languages, this mattered. Loyalty was no longer a patchwork of local bargains but a chain that ran straight to the palace gate.

The transformation did not erase the past. Cavalry remained central; frontier raiders still had their uses. But the fulcrum of Ottoman power had shifted. It would swing decisively in 1453.

1453: Cannons at the Gate

Sultan Mehmed II—just twenty-one—arrived at Constantinople with a dream older than his dynasty and a tool novel enough to make it real. Others had tried to pry open the Byzantine capital. Few brought the patience, the fleet, and the firepower that Mehmed marched to the city’s land walls and floated up to its harbors.

Gunpowder had been making its rude, smoky entrance into Eurasian warfare for generations—mortars, bombards, pyrotechnics that were as dangerous to their crews as to their targets. Mehmed wagered that, applied systematically and at scale, artillery could do what the bow never had: crack the Theodosian Walls, that girdle of stone and brick that had repelled sieges for a thousand years.

He besieged by land and sea, even solving a maritime puzzle with audacity: when the great chains barred his fleet from the Golden Horn, he ordered lighter galleys dragged over greased timbers across the hills and slid them back into the water behind the barrier—an amphibious flanking maneuver that reads like myth until you trace it on a map. On the walls themselves, the Ottomans massed artillery. The star of the battery was a giant bombard, forged by the Hungarian engineer Orban, capable—so contemporaries tell us—of hurling stone balls that weighed as much as a man over nearly a mile.

Day after day, the guns spoke in a language the Byzantines had never heard at such volume. Stone shattered. Mortar dust smeared the air. The city’s defenders patched and prayed. The attackers hauled, swabbed, rammed, fired, and hauled again. On May 29, 1453, breach and assault aligned, and the Ottomans poured through. The world took notice. The city that had personified endurance fell not to arrows but to artillery and organization.

With Constantinople—soon Istanbul—the Ottomans gained a capital worthy of their ambition, a hub at the crossroads of trade and empire. They also committed themselves irrevocably to the new grammar of war: powder, shot, and the logistics to feed them.

The Gunpowder Playbook

If 1453 was the thunderclap, the sixteenth century was the long roll of drums. Historians later called the Ottomans, together with their Safavid and Mughal peers, “gunpowder empires,” and it fit: each leveraged firearms and cannon to project power across vast territories. But the phrase risks flattening the craft into cliché. What made Ottoman gunpowder warfare formidable was not simply possession of guns. It was the integration of technology, training, and supply.

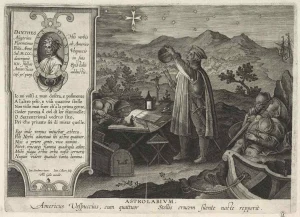

The Janissaries were central again—this time as musketeers. In the late 1400s and early 1500s they began to adopt small arms, experimenting with early hand cannons and then with matchlock muskets, whose slow-burning cord, guided by a lever, brought fire to priming powder in the pan. It was a leap forward from the dangerous, hand-lit touchhole devices. Matchlocks were still temperamental—rain could mute them; wind could snuff them—but in dry conditions they gave infantry a standoff punch that arrows could not match.

The Ottomans worked these weapons into doctrine. Volley fire, for instance, transformed the stop-and-start rhythm of individual reloaders into a continuous sheet of lead. One rank fired, another stepped forward while the first bit cartridges, primed pans, tamped charges, and shoved home balls with ramrods. The result, when executed cleanly, was psychological as much as physical: a wall of noise and smoke that shook the nerves and thinned the line.

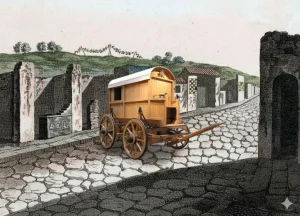

Artillery, too, became more than siege props. Field pieces—lighter guns that could be limbered to teams and repositioned—appeared on battlefields, shredding cavalry charges and suppressing enemy formations. The empire invested in foundries, shot casting, powder mills, and transport. Oxen trudged, barges creaked, roads improved, depots multiplied. Gunpowder armies live and die by their logistics, and for a crucial century the Ottomans kept powder dry and barrels hot.

The dividends were territorial and glittering. Under Suleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566), Ottoman banners snapped from Algiers to Buda to Baghdad. Siegecraft matured into an industrial art; city after city fell not simply because the Ottomans had guns but because they had a system—trained crews, standardized calibers, engineers who could site batteries, miners who could undermine walls, administrators who counted sacks of charcoal and sulfur and saltpeter. The old mobility of the steppe was not abandoned; it was repurposed to move guns.

There were costs. Matchlocks required drill; drill required time; time required money. Powder had to be manufactured, kept dry, and delivered. Lead, copper, iron—these were not pastoral resources; they were industrial ones. The empire that once ran on herds now ran, in part, on mines and mills. That shift would empower the state and, eventually, expose it.

Sea Power, Setbacks, and Slow Decline

An empire with three coasts cannot be a stranger to the sea. The Ottomans began building a navy in the fourteenth century and made it a hammer in the fifteenth. Galleys supported sieges, ferried troops, and snapped up Mediterranean islands and Black Sea ports. The conquest of Constantinople had, after all, been a joint venture—oars and sails as vital as hooves and wheels.

In the sixteenth century the Ottoman fleet met its fiercest rivals: Venice’s maritime republic, Spain’s composite monarchy, Portugal’s oceanic state, and the energetic entrepreneurs of piracy—corsairs who blurred privateering and state service. None loomed larger than Barbaros Hayreddin Pasha—Barbarossa to the West—a corsair-turned-admiral who knit North African ports into Ottoman strategy and beat back Italian and Spanish fleets to make the central Mediterranean an Ottoman lake, at least for a time.

Naval glory was never unchallenged. In 1571 at Lepanto, a Holy League of Christian states dealt the Ottomans a bruising defeat, shattering hundreds of galleys in a maelstrom of cannon and boarding pikes. The loss was material and symbolic, yet not fatal. Ottoman dockyards seethed with new construction; within a few years a rebuilt fleet prowled the seas again. The empire extended its maritime reach into the Atlantic littorals through corsair networks and even planted a flag, briefly, as far afield as the Isle of Lundy in the Bristol Channel—an audacious footnote in a century of sea-borne contests.

Still, storms were gathering. Military decline is never a single event; it is a slow unthreading. Inside the Janissary corps, corruption and politicization crept in. What had been the sultan’s cutting edge dulled into a power bloc that meddled in court and capital, toppling reformist rulers—Osman II’s murder in 1622 marked a chilling precedent—and shaping policy through threat and riot. The mehter still thundered, but discipline thinned when sinecures and bribes bought rank. Equipment lagged, too. Rivals adopted new tactics and technologies—bayonets that turned musketeers into pike-proof infantry, flintlocks that bested damp fuses—more quickly than an ossifying system could absorb them.

Externally, the strategic map shifted. The Habsburgs pressed in Europe; Russia’s star rose in the north and east; France and England, rich with Atlantic wealth and industrial accelerants, modernized their arsenals and navies. The Ottomans could still win—Tunis in 1574, Crete in 1669—but the effort grew costlier, the margins tighter. Defense against multiple fronts taxed even their expansive logistics. The empire’s strength remained real; its trajectory, downward.

None of this cancels what came before. For two centuries the Ottomans were among the best in the world at translating gunpowder into power. They built an administrative-military complex that could besiege with science, fight with fire, and feed the machine that made both possible. If their adaptations later slowed, the earlier feat remains: they bridged the age of the bow to the age of the gun with creativity and force.

Empires are remembered for their crowns and catastrophes; armies are remembered for their weapons. But the Ottoman evolution from horse archer to musketeer, from raid to regiment, is ultimately a story about institutions and imagination. It begins with a simple truth: a bowman on a fast horse can terrify a frontier; he cannot crack a wall. To move from frontier terror to imperial rule, the Ottomans had to learn to crack walls—literal ones of stone and figurative ones of habit.

They did so by inventing and borrowing, recruiting and training, centralizing and supplying. They built a corps of soldiers who owed their lives to the state and then, ironically, lived long enough to challenge it. They mastered engines that made rock flow like sand and sounds that shook cities awake. They harnessed the sea when it served and paid for it when it didn’t. They taught Europe to fear an army that marched to music and fired in waves.

In the end, decline came as it often does: not with a single defeat but with a thousand avoidable frictions—reform blocked here, innovation delayed there, rivals learning, coffers thinning, courtiers scheming. Yet even as the empire’s military edge dulled, its earlier lesson endures. Power, in war, belongs not to the old way or the new on principle, but to those who can tell the difference between them and move, decisively and early, toward what works.

From bows to cannons, from nomad raids to regimented volleys, the Ottomans did exactly that—until they didn’t. Their rise offers models; their fall offers warnings. But the whole of it, seen in one sweep, is a study in adaptation: how a people of the saddle learned to master the gun, and how that mastery, for a glittering century and more, held three continents in its sights.