Abu Bakr ʿAbd Allāh ibn Abī Quḥāfa was born in 573 CE (c. 50 BH) into the Taym branch of the Quraysh, one of Mecca’s smaller but respected clans. His father, Uthman (nick-named Abū Quḥāfa), dealt in textiles and money-lending, and ensured the boy learned reading, poetry memorization, and arithmetic—rare skills in a largely oral society.

By his teens Abu Bakr was accompanying caravans north to Syria and south to Yemen, mastering incense grades, cloth weights, and the unwritten rules of desert credit. Traders admired his quiet fairness so much that “al-Ṣiddīq (the Truthful)” became a widespread honorific long before Islam.

Unlike many Quraysh men, Abu Bakr never drank wine or bowed to household idols, saying he “detested clouds that dim reason.” These personal scruples, along with his generosity toward relatives and freed slaves, created the moral capital that would soon intersect with prophecy.

🤝 An Unbreakable Friendship with Muhammad

Abu Bakr and Muhammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh were near in age and temperament. Both ran family businesses, both shunned Mecca’s factional feuds, and both distrusted the tribal oligarchy that fixed grain prices and marriage alliances. When Muhammad confided his first Qurʾānic revelation (610 CE), Abu Bakr accepted at once; there was no night-long debate, no demand for miracles—just recognition.

His conversion carried strategic weight:

- It signaled to Meccan notables that Islam was more than a fringe movement of impoverished youths.

- It opened quietly negotiated channels of financial relief for new converts, allowing them to buy food and even purchase their own freedom.

The most celebrated case was that of Bilāl ibn Rabāḥ, a Black Abyssinian slave whose owner tortured him in the midday sun. Abu Bakr bought Bilāl for 9 ounces of gold—an extravagant sum for a single laborer—and manumitted him on the spot.

🐪 The Hijra: From Marketplace to Exile

When Quraysh sanctions escalated—from boycotting Muslim stalls to open beatings—Muhammad ordered the community to migrate to Yathrib (Medina). On the eve of departure (16 July 622 CE), assassins surrounded the Prophet’s house. The escape plan hinged on Abu Bakr’s two fast desert camels and his willingness to accompany the Prophet despite a price on their heads.

Three Days in the Cave of Thawr

Hiding in a limestone grotto only 5 km south of Mecca, Abu Bakr steadied the Prophet’s nerves even while whispering fears for his own family left behind. A local Bedouin shepherd erased their footprints each dawn; the Quraysh trackers arrived, peered in, saw a spider’s fresh web, and dismissed the cavity—an episode later immortalised in Qurʾān 9:40.

The eight-day trek that followed—cutting west to the Red Sea, then north to Medina—would become a new calendar epoch, AH 1.

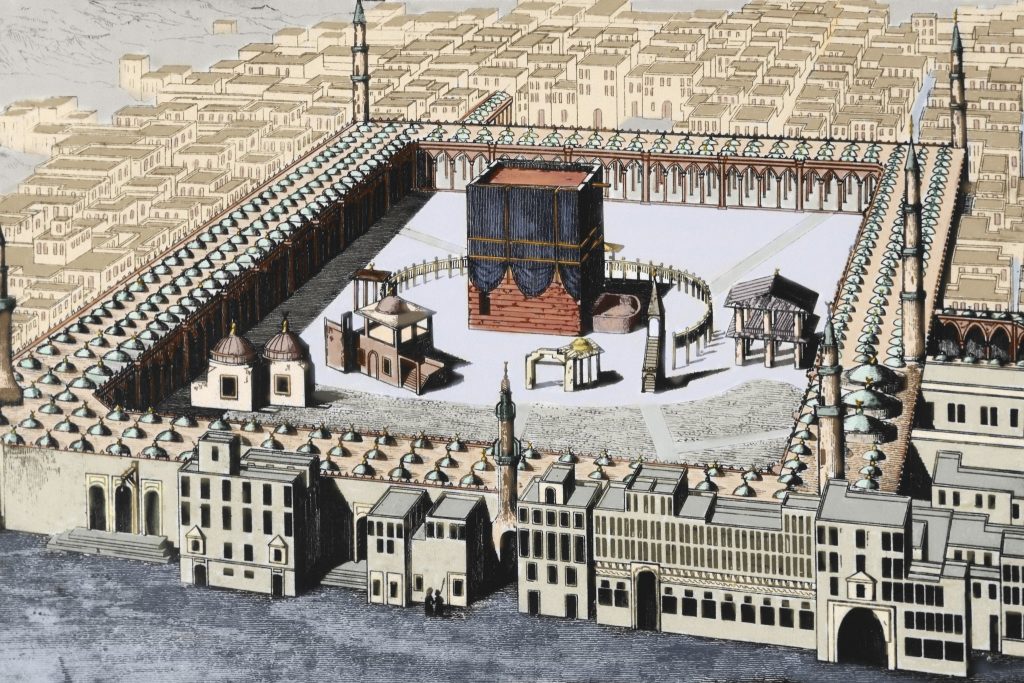

🕌 Building a Community in Medina

Abu Bakr’s house stood on the east wall of the Prophet’s Mosque, linked by a private gate so Muhammad could consult him with a single knock. His duties during the first ten years of the umma included:

- Treasurer of the public donations, recording who paid zakāt grain or silver and how it was redistributed to orphans and widows.

- Diplomatic envoy to tribes such as Banū Kilāb and Banū Tamīm, whose pledges of security kept Medina’s hinterland wheat routes open.

- Commander of small cavalry detachments (sariyāt) sent to monitor hostile caravans.

At the Battles of Badr, Uḥud, and al-Khandaq

- Badr (17 March 624) – Abu Bakr stayed at Muhammad’s side in the command tent, counselling restraint when young zealots urged a night raid on the Quraysh camp.

- Uḥud (23 March 625) – When rumours of the Prophet’s death spread, Abu Bakr formed a makeshift shield wall to buy time until Muhammad emerged wounded but alive.

- Trench Siege (April 627) – He helped survey the ditch’s western sector, using decades-old caravan maps of basalt outcrops to predict cavalry approach lines.

⚖️ The Turbulent Hours after Prophetic Death

Muhammad died just after midday on 8 June 632 CE. Panic coursed through Medina. Some men, including ʿUmar, refused to believe the Prophet could die. Abu Bakr entered the chamber, drew back the cloak, kissed Muhammad’s brow, and proclaimed:

“Whoever worships Muhammad—know that Muhammad has died. Whoever worships God—know that God lives, undying.”

At the portico of Banū Sāʿida, Ansār chiefs proposed a dual leadership—one caliph from Medina, one from Quraysh—to keep power balanced. Abu Bakr countered that Islam mandated a single imam to avoid tribal partitions. His argument rested on two proofs:

- Muhammad had commanded Abu Bakr, and no one else, to lead prayer during his last illness—a sign Muslims were already following him in spiritual matters.

- Quraysh, though few in number, linked all Arab tribes through pilgrimage and lineage; their neutral position prevented jealousy among competing Bedouin confederations.

ʿUmar grasped Abu Bakr’s hand in allegiance; others followed, some reluctantly, some eagerly, but the deed was sealed before midnight.

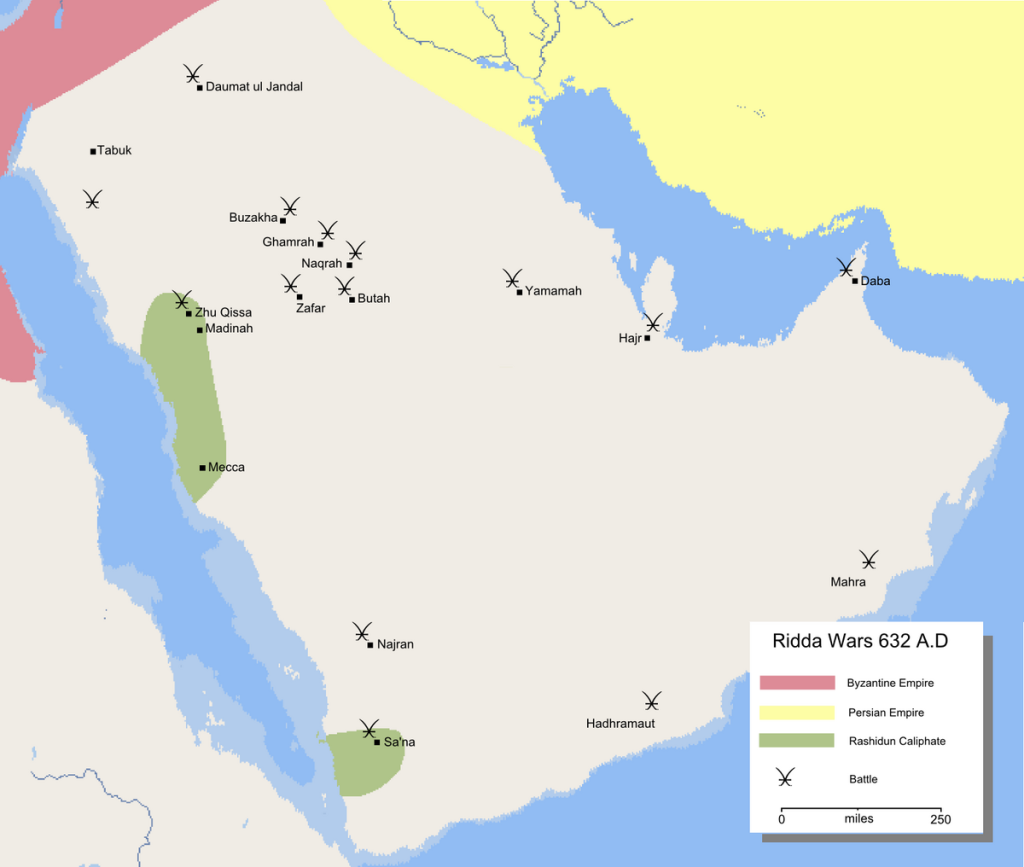

🛡️ Ridda Wars: Holding Arabia Together

Why Rebellion Spread

Within weeks, letters arrived from central Arabia: Musaylima of Yamāma and Tulayḥa of Najd claimed prophethood. More alarming, tribes that had paid zakāt to Muhammad now argued their treaty ended with his death.

Strategic Dilemma

Senior Companions urged diplomatic delay, fearing simultaneous wars on three fronts. Abu Bakr’s reply became legendary:

“If they withhold even a rope they once paid in charity, I will fight them for it.”

He organized 11 regional corps (each 3-4 000 men) and appointed Khālid ibn al-Walīd over the main thrust toward Yamāma.

Major Engagements

| Month (633 CE) | Battle | Outcome | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Abraq (Najd) | Victory | Broke Tulayḥa’s coalition; he later embraced Islam. |

| Feb | Zafar (Yemen) | Victory | Restored seaport customs revenue to Medina. |

| March–April | Buzākhā (central Najd) | Victory | Ended largest nomad confederation revolt. |

| Dec | ʿAqrabāʾ / “Garden of Death” | Costly Victory | Musaylima slain; 1 200 Muslims fell, including 70 Qurʾān memorisers. |

By February 634 CE Arabia was again forwarding zakāt camel trains to Medina, and tribal horsemen once divided now fought under a single standard.

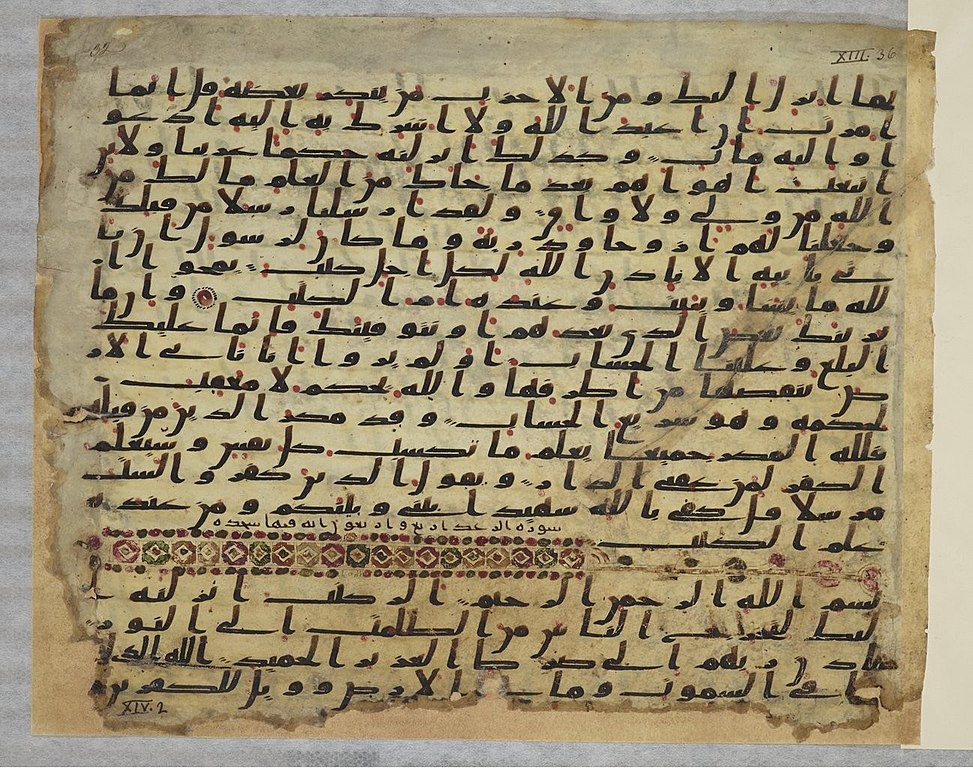

📜 Preserving the Qurʾān: The First Mushaf

The massacre at ʿAqrabāʾ shocked Medina: dozens of veteran ḥuffāẓ lay dead. ʿUmar pressed the Caliph: “War may take more of the Qurʾān than war takes of us.” Abu Bakr hesitated—collecting the verses in one volume felt like altering revelation—but eventually commissioned Zayd ibn Thābit to gather parchments, scapulae, and eyewitness testimonies.

- Zayd accepted written fragments only if two Companions verified both the text and its context.

- The sheets were tied with silk and stored under Abu Bakr’s bed. After his death they passed to ʿUmar, then to Ḥafṣa bint ʿUmar, and finally served as the exemplar for ʿUthmān’s ʿUthmānic codices.

🏛️ Governance and Social Policy

Personal Austerity

Abu Bakr refused a salary, continuing to sell cloth in the market until ʿAlī and ʿUthmān insisted the state assign him 2 dirhams per day—barely enough for coarse bread and oil. Upon his death he instructed his heir to return the government’s camel, servant, and cloak.

Bayt al-Māl (Public Treasury)

- Revenues: zakāt livestock, one-fifth of war booty (khums), and customs at Yemen’s Aden port.

- Expenditures: stipends for orphans, pensions for widows of martyrs, and seed grain loans to drought-hit oases.

- Records: a single wooden tablet listing recipients by clan, often revised in Abu Bakr’s own hand at night.

Rule of Law

The Caliph proclaimed, “The weak among you is strong with me until I wrest from him his due; the strong among you is weak with me until I wrest from him what he owes.” He dismissed a favored governor in Bahrain for gifting him perfume without market payment, declaring the gesture a bribe.

🌍 First Blows Against the Empires

With Arabia secure, Abu Bakr sought to pre-empt Byzantine and Sāsānian counter-moves:

- Khālid ibn al-Walīd diverted from central Arabia to Iraq’s lower Euphrates, routing Sāsānian garrisons at al-Hīra and Ayn al-Tamr (fall 633).

- ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ advanced toward the Levant, clashing with Byzantine foederati near Ajnādayn (July 634).

While these raids were small compared with later conquests, they:

- Tested Arab cavalry tactics against armored cataphracts.

- Captured surplus wheat that fed drought-stricken Medina.

- Delivered psychological shock to two superpowers unprepared for a united Arabian polity.

🪦 Final Illness and Succession

Returning from a spring inspection of Syrian troops, Abu Bakr developed chills that worsened into fever (likely malaria). Over two weeks his voice faded, but he convened a council and nominated ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb. Some Companions feared ʿUmar’s stern temper; Abu Bakr replied, “He is harsh because you are soft; were he leader, he would soften as necessary.”

He died on 23 August 634 CE (22 Jumādā II 13 AH) at age 61. According to ʿĀʾisha, his daughter:

“He left neither a dinar nor a dirham, a slave nor a goat—only his faith and the dress upon him.”

Burial took place the same night in the Prophet’s Chamber, slightly behind and to the right of Muhammad’s resting place.

🌟 Legacy: Charting the Umma’s Course

Abu Bakr ruled just 27 months, yet historians—Sunni, Shiʿa, and secular alike—agree his decisions determined whether Islam would fracture or flourish:

- Unified Arabia – By declaring zakāt non-negotiable, he fused spiritual practice with fiscal loyalty.

- Saved the Qurʾān – His compilation initiative ensured later generations read one uncorrupted text.

- Professionalized the military – Corps-level organization and revenue stipends replaced ad-hoc tribal levies.

- Modeled accountable leadership – His austere personal life undercut any claim that the caliphate was a path to enrichment.

Shiʿa chronicles dispute the legality of his election vis-à-vis ʿAlī, yet even they acknowledge Abu Bakr’s piety and early sacrifices. Modern historians liken his role to that of a “constitutional founder”—he interpreted prophetic precedent into executable governance.

🧭 Conclusion: The Compass and the Horizon

A prophet could galvanize hearts; a successor had to administer grain, treaties, and justice. Abu Bakr stepped from the intimacy of friendship into the loneliness of command, steering a fragile coalition through civil revolt, famine, and imperial threats. By the time the fever gripped him, the umma had outgrown the oasis town that birthed it, poised to stride across three continents.

Understanding Abu Bakr therefore means grappling with the moment when a revelation became a civilization—and with the quiet merchant whose unwavering truthfulness guided that transformation.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Dunsterforce: The Race to Baku, 1918

The Hollow Earth: From Halley to UFOs

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

Locke and the Morality in Early Modern England

Pauline Bonaparte as Canova’s Venus Victrix: Scandal, Power, and a Marble Legend

Pope Leo X Who Helped Ignite the Reformation

The Women Who Turned Music Theory into Games

Scandal, Sorcery, and Secrets in Louis XIV’s Court

The Sacred Power of Medieval Queens

Trump elected and the on-going California Wildfire: Is a God’s Message?

A Historical Jesus: True or Untrue

Louis XIV: The Sun King’s Long Reign