For more than a century, scholars have argued over how Britain transformed from a land of Celtic-speaking Britons under Rome to a predominantly Germanic-speaking society by the seventh century. Was this change driven by a large-scale influx of migrants from across the North Sea, or did relatively few newcomers arrive while native Britons gradually adopted Anglo-Saxon language and culture? Recent advances in ancient DNA have pushed this debate into new territory—and reshaped the consensus.

From Chronicle to Counter-Narrative

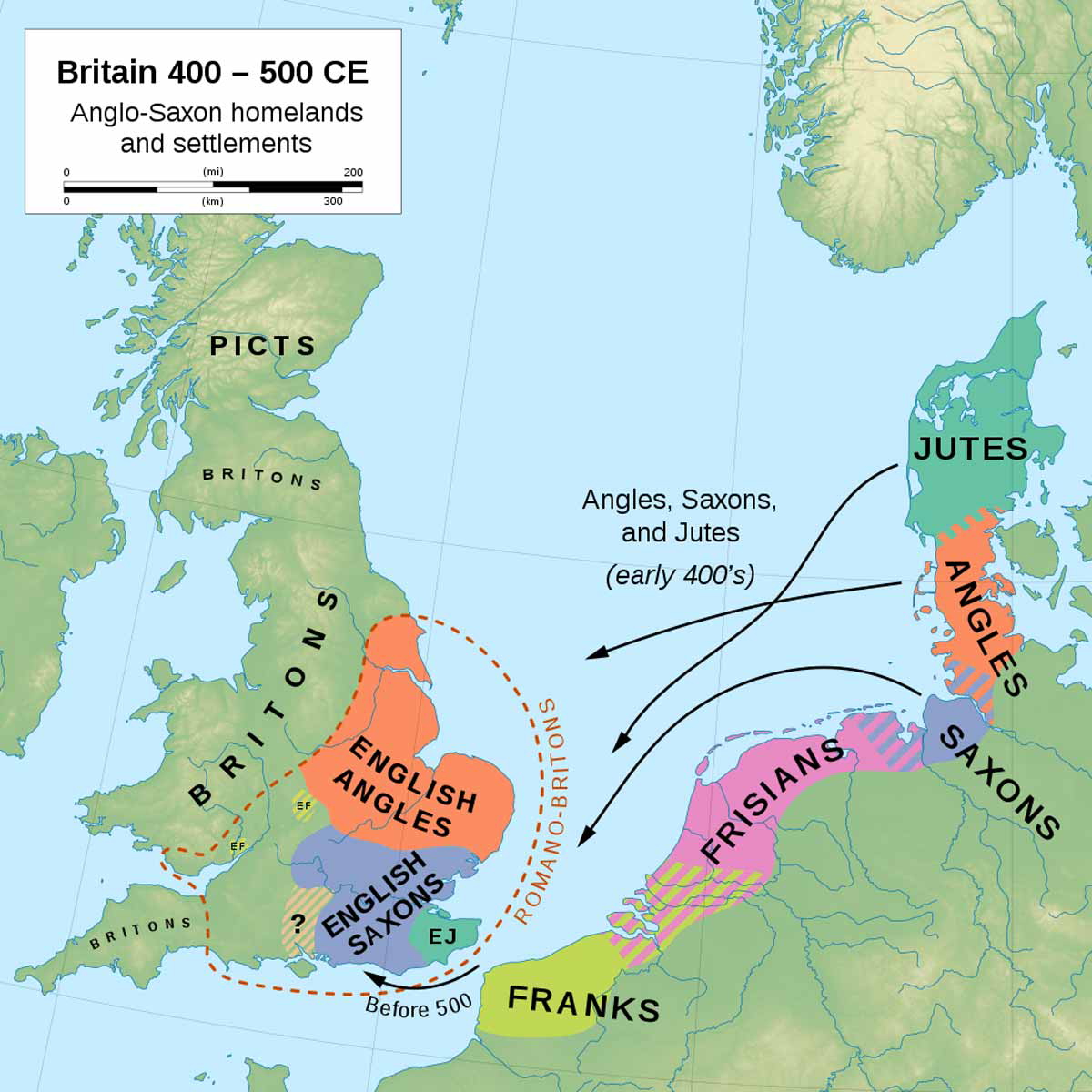

Medieval writers tell a vivid story: after Rome’s withdrawal, British leaders hired Germanic mercenaries who soon turned on their employers, triggering waves of settlement and conquest by Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Over generations, Britons were killed, displaced, or forced west into Wales and the West Country.

Twentieth-century archaeology complicated that picture. Clear layers of destruction were often absent, and many material changes looked gradual. A “minimalist” view emerged: perhaps only modest numbers of migrants arrived, and cultural change—language, customs, burial rites—spread through emulation rather than demographic replacement. Some went further, doubting significant migration at all.

Early Genetic Clues—and Their Limits

As genetic tools matured, researchers tested these competing models by comparing modern DNA from England with that of Wales and continental Europe. Several studies suggested that people in eastern and southern England carried measurable—but not overwhelming—continental Germanic ancestry. Estimates ranged roughly from 10–40 percent overall, with some regions of eastern England showing 25–50 percent. These findings seemed to fit the minimalist reading: the newcomers were present, but always a minority, and perhaps their influence was primarily cultural.

Yet there was a fundamental weakness in this approach. Modern genomes are palimpsests, shaped by centuries of later movement and mixing. Inferring early medieval events from present-day DNA risks blurring or diluting past signals.

A Turning Point: Ancient DNA at Scale

In 2022, a landmark study tackled the problem directly by sequencing thousands of ancient genomes from across Europe and Britain dated between 200 and 1300 CE. Instead of extrapolating from living populations, the research tracked ancestry through time and space during the very centuries in question.

The results were striking. Early medieval individuals from eastern England showed a dramatic increase in ancestry closely related to early medieval and modern populations of northern Germany and Denmark. In some eastern communities, individuals derived as much as 76 percent of their ancestry from this continental North Sea zone. Regional variation was real—western areas showed lower proportions—but the broad pattern was unmistakable: large-scale migration across the North Sea was central to the formation of early English populations. This was not a mere trickle or a change led by a small elite.

Migration, Women, and the Texture of Settlement

One of the study’s most discussed findings was the substantial presence of women among the migrants. Some took this to mean the process must have been peaceful. That inference does not follow. Medieval narratives describe groups seeking land to settle with families, not simply armies seeking tribute. If entire kin groups moved, one would expect both men and women to cross the sea. The genomic evidence is therefore compatible with a range of scenarios—from violent conquest and seizure of farmland to negotiated settlement—rather than a single, simple story.

Crucially, the ancient DNA also shows that migrants and locals often lived side by side. In some cemeteries, individuals with largely continental ancestry were buried near others with predominantly local ancestry; in certain sites there are hints of social separation, in others none at all. This mosaic points to complex local dynamics: integration and intermarriage in some communities; stratification, displacement, or tension in others.

What Genetics Can—and Cannot—Tell Us

Taken together, the genetic evidence overturns the strongest minimalist claims. The early English gene pool was shaped by substantial migration from continental northern Europe, particularly in the east and southeast. That demographic reality helps explain the rapid and enduring shift in language and material culture.

At the same time, genetics alone cannot adjudicate the precise level of violence. Bones and genomes record movement and kinship more clearly than motives, treaties, or battlefield outcomes. Archaeology and texts remain indispensable for assessing conflict, coercion, and political structures. It is entirely plausible that decades of competition over land and resources involved both warfare and negotiated accommodation; neither total population replacement nor purely peaceful diffusion fits all the evidence everywhere.

The Emerging Picture

A decade ago, many genetic studies based on modern DNA pointed toward limited migration and extensive cultural adoption. The large ancient-DNA dataset published in 2022 reframes that view. It shows that early medieval England—especially in the east—absorbed a major influx of people whose ancestry ties them to Germany and Denmark, with some communities reflecting continental ancestry levels well above half.

This does not mean the newcomers erased the island’s earlier inhabitants. Rather, early medieval England took shape through mass movement and sustained mixing, producing local societies that ranged from tightly integrated to socially segmented. The new genetics thus supports a middle path between two older extremes: neither pure cultural osmosis nor simple replacement, but a transformative migration that intertwined with the lives of those already in Britain—sometimes peacefully, sometimes not—and set the foundations of English identity for centuries to come.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

The Eye of Horus: What it’s meaning

Louis XIV: The Sun King’s Long Reign

Edgar Allan Poe: The Mastermind Behind Modern Horror

The Women Who Turned Music Theory into Games

5 Uncanny Coincidences in U.S. History

The Tokugawa Shogunate: Isolation and Cultural Renaissance

10 Historical Figures Behind Chemical Element Names

The Ten Plagues of Egypt: A Biblical Account of God’s Power

How the 12th Century Invented the “Enemies” of Medieval Europe

The Quiet Takeover of Greenland

How American Lend-Lease Trucks Fueled the Soviet War Machine in WWII

How TV Rewrite the Norman Conquest