After centuries of uneven care—and decades of neglect—Aden’s extraordinary waterworks are finally set for a true restoration. Hewn directly into volcanic rock at least two millennia ago, the Tawila tanks once fed a port city that clings to the rim of an extinct volcano. Now, a UN-backed project aims to return them to their original purpose: storing floodwater, protecting the town, and supplying precious fresh water.

A masterpiece without a maker

No inscriptions, no dates, no dedicatory plaques—only stone and ingenuity. Taxi drivers spin legends of the Queen of Sheba, but historians can only speculate. Some once attributed the complex to the Persian occupation in the sixth century CE; more likely, it belongs to the first millennium BCE, when highland peoples—especially the Himyarites, rivals of the Sabaeans—were mastering hydrology, policing Red Sea ports, and taxing the caravans that linked Egypt and Arabia. Whatever the authorship, the tanks sit within a broader Arabian tradition of dams, cisterns, and catchments—albeit on a scale unmatched in Yemen or across to the Horn of Africa.

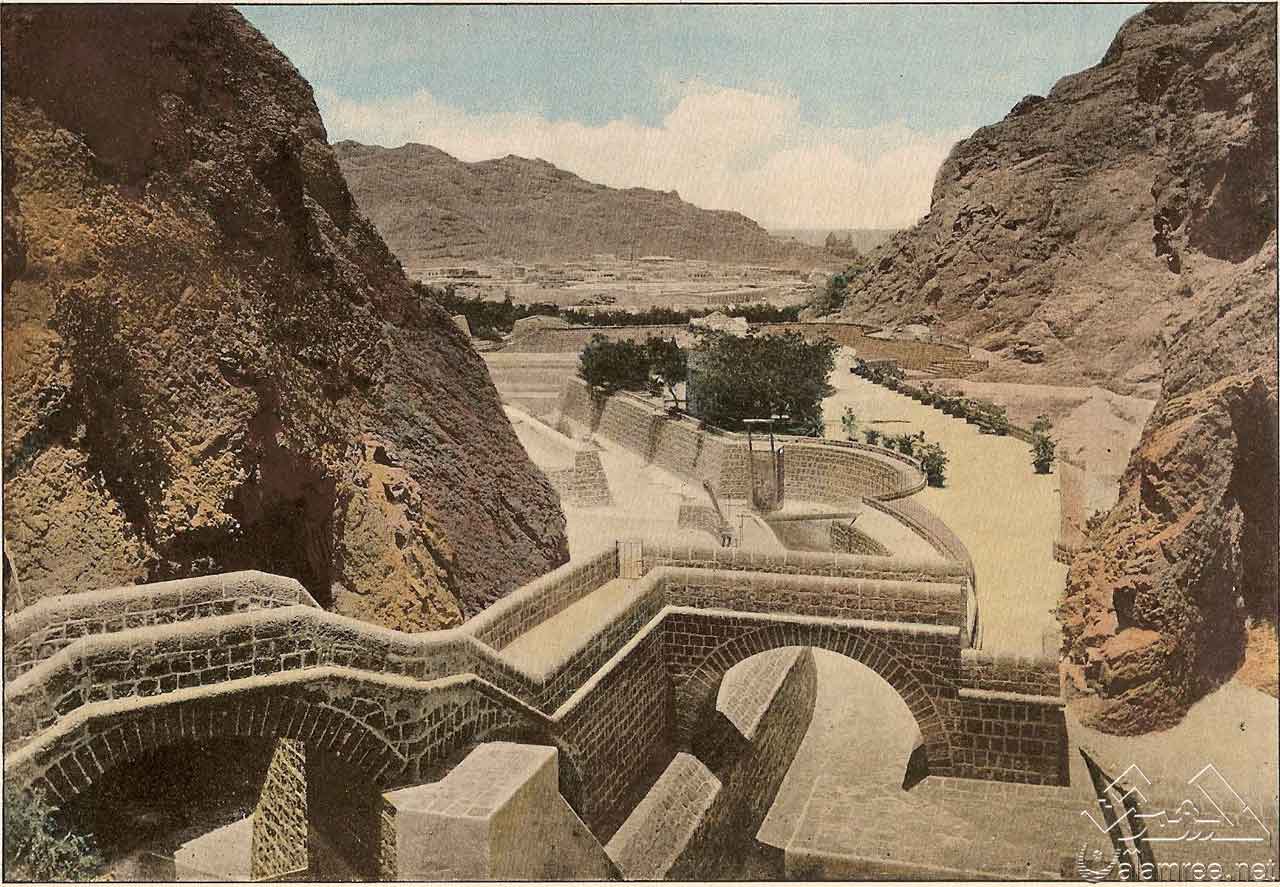

A port on a volcano—and a problem to solve

Aden is a natural harbor—an islanded volcano tethered to the mainland by a narrow spit, its black cliffs rearing to 1,700 feet. Rain here is sporadic, violent, and precious. Early engineers watched how stormwater tore down ravines to the sea, then captured and disciplined that flow: carving cisterns, dams, canals, retaining walls, weirs, sluices, and spillways down the main gorge.

Because basalt is porous, they lined dams with brick and sea-sand mortar; cisterns were faced with limestone and plaster to make them watertight. At full capacity, the system could hold an estimated 20 million gallons—a civic battery charged by fickle skies.

Decline—and a Victorian revival

By around 1500, focus shifted to sweet-water wells, which sufficed as Aden waned after the Cape route rerouted global trade. Channels silted, walls collapsed, and memory dimmed.

When the British took Aden in the nineteenth century, they recognized the system’s promise. In 1856 Captain Lambert Playfair led major works; a vast lower basin still bore his name. Yet not all interventions were sympathetic. Writing in the 1950s, antiquities director C. H. Inge faulted blasting that obliterated fine runnels—the delicate feeder channels that once diverted every trickle off near-vertical cliffs. The overall system survived, but its finesse was dulled.

Neglect, floods—and a turning point

Since the British departure, the tanks have been valued mainly as a tourist site, not critical infrastructure. Meanwhile, Aden’s wadis—rocky storm channels that should run free to the sea—were built over. In a cloudburst four years ago, those obstructions amplified flooding and loss of life, a stark lesson in what these ancient works were designed to prevent.

The plan: restore function, not just a façade

A joint UNDP–UNESCO initiative now proposes a ground-up restoration:

- Recreate original finishes using limestone and historically plausible mortar and plaster recipes to re-seal basins and walls.

- Rebuild feeder runnels and minor channels that once swept “every drop” into storage.

- Clear and safeguard wadis below the tanks so floodwaters can pass safely through the town to the sea.

“This is a unique restoration,” says project lead Adel Al-Hammady. It revives a historic landmark and reinstates its core purpose: flood protection and water supply for the district of Crater.

Why it matters

- Climate logic: In arid coasts facing erratic rain, distributed storage and managed conveyance are cost-effective resilience.

- Cultural continuity: Restoring the working system, not just the look, honors the original engineers’ intent.

- Urban safety: Open wadis and sound basins reduce flood risk—exactly what recent storms proved Aden needs.

And there’s a scholarly bonus: a careful program of works could uncover new clues—a construction layer, a tool mark, a reused block—that finally narrows the question of who carved Aden’s stone reservoirs.

For now, the Tawila tanks are poised for a second life: ancient engineering serving a modern city, once again catching the rain before it is gone.