In May 2025, Keir Starmer’s government did something that felt oddly familiar: it backtracked on a proposal to means-test the winter fuel allowance, the annual payment pensioners have received since 1997.

On paper, the reform made sense. Public finances are tight. If you don’t want big tax rises on working-age people and you can’t conjure rapid growth on demand, you end up staring at cuts. And if you’re forced to choose, it’s not irrational to ask: do the best-off pensioners—especially once housing costs are factored in—really need the state to chip in for their heating bills?

Yet the politics was brutal. Pensioners are close to one-fifth of the population, and the public mood tends to follow them. Polling suggested the wider electorate didn’t want the change either. So the government blinked.

This isn’t just a Starmer story. It’s a Britain story. And it has been the same story since the welfare state was born.

Because financing old age has always been the welfare state’s hardest problem: morally charged, electorally explosive, and structurally difficult to reform without creating a new injustice somewhere else.

The original warning shot: Beveridge in 1942

Back in 1942, William Beveridge—writing what later became the moral blueprint for the postwar welfare state—told MPs something that still echoes today: improving pensions would force ugly choices.

His preferred solution was a universal pension for over-65s, but with a catch. Start low. Increase gradually over 20 years as workers build up a surplus of contributions to fund their own retirement. In other words: make it sustainable, even if it’s politically painful at first.

But Labour’s Jim Griffiths—then Minister of National Insurance—pushed the other way. He argued that people already retired had lived through a punishing sequence: war in youth, depression in middle age, then the existential strain of 1940. They shouldn’t be told, effectively, “wait two decades while the spreadsheet balances”.

So full pensions were paid immediately—and the price of that moral choice was predictable: pensions were set below subsistence level. Not generous enough to live on, but expensive enough to make everyone nervous.

That trade-off—do it now, but keep it meagre—became one of the defining tensions of the post-1945 settlement.

Postwar Britain: a welfare state with a hole in it

For years after 1945, the political mood often implied poverty was now a rare exception, because the system “covered everyone.” But almost everyone quietly admitted there was one glaring exception to the postwar optimism: pensioners.

Even in the late 1950s, when Harold Macmillan was telling voters they’d “never had it so good,” pensioners were the group most politicians wouldn’t include in the boast.

Why? Because the demographics were shifting fast.

Britain had more older people than ever, in absolute numbers and as a share of the population. The proportion of men over 65 and women over 60 rose sharply in the first half of the century, and by the end of the 1950s millions more were expected to be drawing pensions than when the postwar scheme began.

Treasury instincts were simple: keep costs down. But the result was a system that satisfied nobody:

- The state pension was too low for large numbers of retirees.

- Pensioners increasingly had to apply for means-tested support from the National Assistance Board (NAB), effectively “going cap in hand.”

- By the late 1950s, two-thirds of NAB claimants were pensioners.

So the welfare state ended up with a bitter paradox: the “universal” pension existed, but huge numbers still needed means-tested top-ups to survive. That meant bureaucracy, stigma, and constant political pressure.

And then there was the opposite fear: what if it’s all too expensive anyway?

A Conservative-appointed committee in the early 1950s argued it was nearly impossible to design a pension both livable and Treasury-friendly, and floated the nuclear option: push the retirement age back to 70.

Politically, that was dynamite. No government wanted the electoral fallout. But the question remained: how do you put more money into pensions without blowing up the entire model?

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

Your contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

The Beveridge trap: equality that caps generosity

Beveridge’s system had an egalitarian beauty: flat-rate contributions and flat-rate benefits. Everyone paid in; everyone got the same.

But that elegance came with a hard ceiling: the whole thing was tethered to what the lowest-paid workers could afford to contribute. So if you wanted a materially decent pension for everyone, you either needed:

- much higher contributions (politically and economically risky), or

- a bigger Treasury subsidy (politically contested and fiscally heavy), or

- some kind of earnings-related structure (a redesign that creates winners and losers).

Unable to do the big redesign, politicians fell back on something that felt safer: occupational and private pensions.

And that’s where a new inequality hardened.

A major social policy thinker, Richard Titmuss, called it “two nations in old age”:

- those with occupational/private pensions, who could retire comfortably,

- and those stuck with the state pension, which everyone knew was not enough.

That divide wasn’t an accident. It became an unofficial patch for the state’s shortcomings.

Labour’s big dream: “half pay on retirement”

In opposition during the 1950s, parts of Labour started thinking: incremental tweaks won’t fix this. They wanted a modern welfare state, built for a richer country and a more complex economy.

In 1957, Labour proposed “National Superannuation,” an earnings-related scheme:

- you contribute proportionally to income,

- your pension reflects lifetime earnings,

- and the design can embed redistribution so the poorest end up better protected.

Labour sold it with a brilliantly simple promise: “half pay on retirement.” The pamphlet campaign was a hit.

But it never became reality. Why?

Because earnings-related pensions have consequences. They imply a more fundamental reshaping of social security, and many politicians didn’t have the stomach for the chain reaction: what else would need to be rebuilt if pensions changed so radically?

Conservative governments also had ideological objections. They preferred private provision, worried about expanding the state, and didn’t want to undermine the private pension industry. They attacked Labour’s scheme, pounced on technical errors, and then—tellingly—announced a weaker imitation: an earnings-related add-on that often failed to keep up with inflation, signalling the real intention was to raise revenue more than raise dignity.

When Labour returned to power under Harold Wilson in 1964, you might expect the big overhaul. Instead, like so many ambitious reform agendas, it slid down the priority list. A distant cousin of the original dream—SERPS—arrived in the late 1970s, heavily watered down after two decades of political hesitation.

The pattern was clear: bold pension reform looks great on paper and terrible in government.

The modern pivot: from poverty relief to fiscal strain

After the Second World War, the dominant failure was simple: pensioners were poor, and the system didn’t meet their needs.

But later, the problem shifted. Governments began improving support for pensioners, but without fully addressing how to pay for it as the population aged. Over time, generosity grew faster than the political system could comfortably sustain.

The ultimate symbol of that is the triple lock, which guarantees the state pension rises each year by the highest of:

- inflation,

- average earnings,

- or 2%.

The triple lock is popular because it feels like protection. But it also makes pension spending structurally hard to control, especially in periods when inflation or earnings spike.

Then there’s the winter fuel allowance, introduced in 1997 when pensioners were widely seen as Britain’s poorest demographic. Fast-forward a quarter century and pensioners as a whole are no longer the poorest group; in many ways they’ve become among the more secure—though pensioner poverty still exists and can be severe.

So the debate evolves into a political nightmare:

- Some older people genuinely struggle and need help.

- Some older people are comfortable, even affluent.

- Universal benefits become harder to justify fiscally.

- But means-testing triggers anger, distrust, and fear—especially among people who feel they “paid in.”

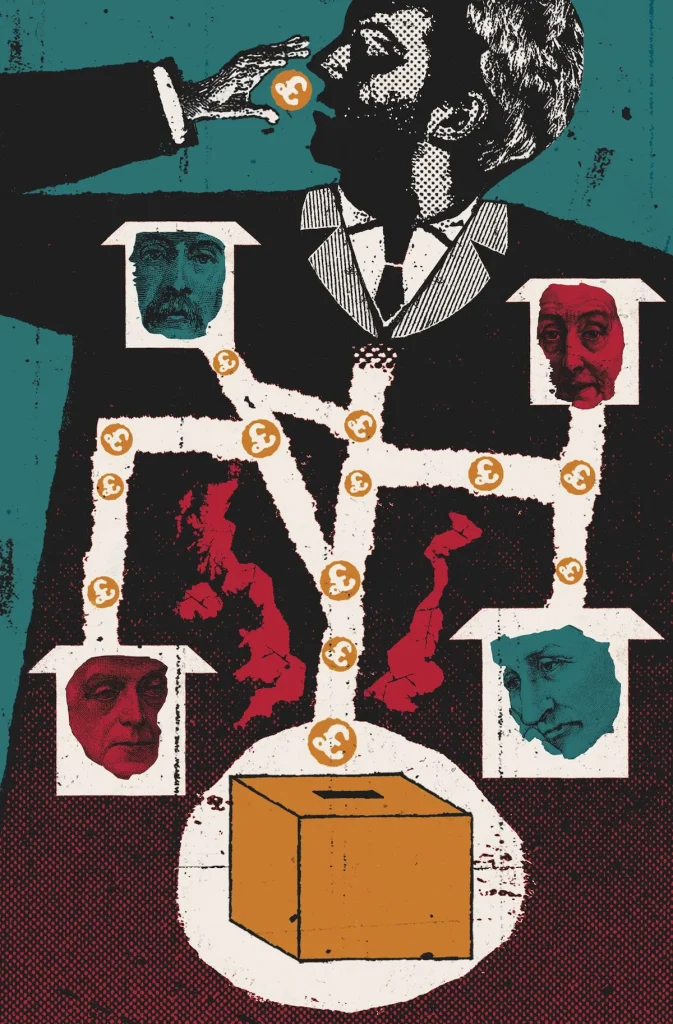

The real obstacle: identity, not arithmetic

Here’s the core issue: the state pension is one of the last parts of the welfare system that still feels like a contract rather than charity.

Many pensioners don’t think of it as “government help.” They think of it as earned—a return on contributions made over a lifetime. That perception is deeply rooted in the old contributory principle. It’s why pension politics is uniquely radioactive: reforms feel like breaking a promise, even if the numbers say the system must change.

That’s why governments keep circling the same dilemma:

- Universal benefits are expensive and increasingly hard to defend.

- Means-tested benefits are cheaper and better targeted, but politically toxic.

So leaders flinch. Over and over again.

Do crises create reform?

Historically, major change often needs unusual conditions. After 1945, the context of war—shared sacrifice, a sense of national rebuilding—made big social policy decisions easier to justify.

But even that lesson has limits. If a world war can reshape the welfare state, what about something like Covid-19, which was disruptive on a vast scale? Did it produce a comparable reform moment? Not really. If anything, it highlighted how quickly emergency spending can happen—and how quickly long-term structural reform gets postponed again.

Which leaves a bleak but honest possibility: the reform moment may still be ahead, forced by demographic pressure, fiscal reality, and political exhaustion.

The depressing conclusion—and the only hopeful one

The story from Beveridge to Starmer is not that British politicians are stupid. It’s that the system creates a trap:

- voters want dignity and security in old age,

- the state pension is culturally treated as earned,

- demographics make it increasingly costly,

- means-testing feels like betrayal,

- and any real overhaul produces obvious losers (who will vote).

So governments resort to half-measures, tweaks, delays, and U-turns.

If there’s a hopeful angle, it’s this: attention spans may be longer than politicians assume. People can handle complexity if you speak plainly. A serious reformer would have to do what British politics rarely does well—tell the country the truth:

we can’t have everything at once: universal payments, ever-rising guarantees, low taxes, and balanced books. Something has to give—and unless we choose deliberately, reality will choose for us.

If you want, I can turn this into a tighter Substack-style piece with a sharper opening hook and a punchier ending (same content, more “voice”).

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

MSG: The “Umami” Discovery—and a Long, Unfair Scare

A Student Revolt in Ancient Athens

Jan Smuts: South African Leader, Global Statesman

The Sacred Power of Medieval Queens

Edward I: England’s Warrior King

The Legacy of Black Hawk: A Sauk Leader’s Fight for His People

How to Read the 6 Jane Austen Novels

Petra: The Rose-Red City and the Scented Road

Locke and the Morality in Early Modern England

Church Life in the Second and Third Centuries

5 Uncanny Coincidences in U.S. History

Machiavelli, Luther, and the Rise of Modern Moral Thought