In the quiet corners of the Roman Empire, far from the clamor of palaces and the clash of legions, a different revolution was unfolding. It was not waged with swords, but with faith. By the second century, the small band of Jesus-followers who once huddled in Jerusalem had grown into a scattered yet vibrant movement stretching from North Africa to Gaul, from Syria to Spain. This was the early Church in its formative centuries—persecuted, misunderstood, yet remarkably resilient.

It was a church without basilicas, without political power, and without public visibility. But it was alive. And underground, it flourished.

From House to House

Christianity in the second and third centuries had no grand cathedrals or open gatherings in city centers. Instead, worship took place in private homes. These house churches, often led by local elders or bishops, were the heartbeat of Christian life. The faithful would gather on Sundays, usually before dawn, to read Scripture, sing psalms, offer prayers, and partake in the Eucharist—the sacred meal commemorating the Last Supper.

These meetings were intimate and rich with symbolism. A meal might follow the worship, called an agape or “love feast,” underscoring the familial nature of the Church. The believers saw themselves not merely as members of a religious group but as brothers and sisters in a spiritual family—one bound not by blood, but by baptism.

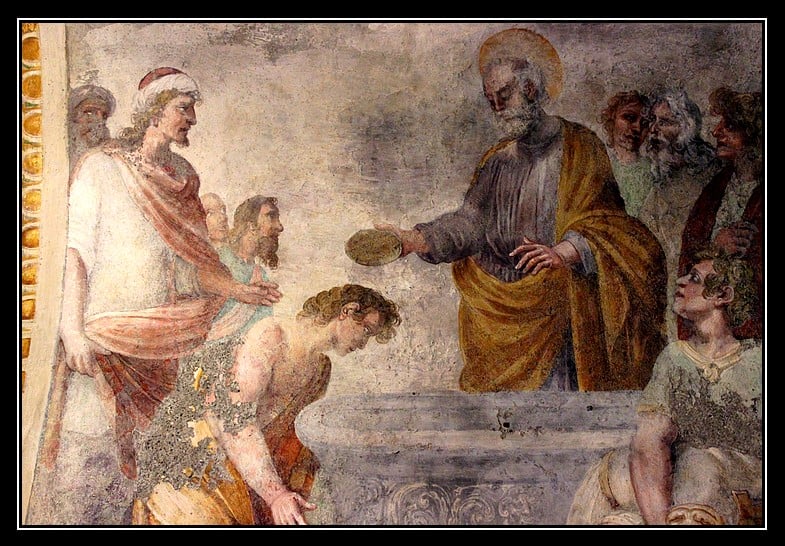

Baptism, in fact, was the threshold into this new family. Often conducted after months—sometimes years—of instruction, it marked the beginning of a radical new life. Converts would renounce Satan and the sinful world, be immersed in water, and rise up into a new identity in Christ. The Church was no mere club; it was a covenant community.

Persecution and Courage

Life as a Christian in these centuries was a delicate balance between devotion and danger. The Roman Empire, suspicious of secretive sects, saw Christians as a threat—not because they carried weapons, but because they refused to worship the emperor. This refusal, perceived as political defiance, brought waves of persecution.

The second century saw episodic crackdowns. The third century, particularly under emperors like Decius and Valerian, brought empire-wide efforts to stamp out the faith. Christians were arrested, tortured, and executed. Martyrs like Polycarp of Smyrna, Perpetua of Carthage, and many others became symbols of defiant faith.

But persecution didn’t extinguish the Church—it refined it. The willingness to suffer, even die, for Christ became the ultimate witness (martyria) to the truth of the gospel. Christians were taught that martyrdom was not to be sought but welcomed if it came. In the amphitheaters, they faced beasts and blades with hymns on their lips.

Structure and Leadership

By the mid-second century, the Church had already begun to formalize its structure. At the head of each local church stood a bishop (episkopos), assisted by elders (presbyters) and deacons (diakonoi). These leaders were responsible for teaching sound doctrine, maintaining discipline, and organizing the life of the community.

The authority of bishops became particularly important in maintaining unity and orthodoxy. As various interpretations of Christianity sprang up—some influenced by Gnosticism or Marcionism—bishops like Irenaeus of Lyon and Ignatius of Antioch emphasized the importance of apostolic succession. The true Church, they argued, was the one that preserved the teaching of the apostles, handed down through the bishops.

The bishop was more than a teacher. He was a symbol of unity, a guardian of doctrine, and a pastor to the flock. Letters from bishops to churches in other cities became an early form of inter-church communication and theological reflection.

Scripture and Teaching

During these centuries, there was no single “Bible” as we know it today. Communities circulated collections of apostolic letters, gospels, and Hebrew Scriptures (usually in Greek translation). The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were widely accepted by the end of the second century, while letters attributed to Paul and other apostles were read in worship.

Apologists like Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, and Tertullian emerged to defend the faith against pagan critics and internal heresies. Their writings were instrumental in clarifying Christian theology, articulating doctrines about God, Christ, salvation, and the Church.

Theology in these centuries was not a detached academic pursuit—it was born in conflict and nurtured in worship. It responded to questions like: Who is Jesus? How is he both God and man? What does salvation mean? What is the nature of the Church?

More Stories

Worship and the Sacred Life

Early Christian worship was simple, solemn, and rich with spiritual meaning. The Eucharist, or “breaking of bread,” was central. Presided over by the bishop or elder, the bread and wine were received not just as symbols, but as participation in the body and blood of Christ.

Prayers were offered for the Church, the world, and even the emperor—though Christians did not worship him. Scripture was read aloud, often followed by a sermon. Psalms were sung or chanted. A kiss of peace was exchanged before communion, reinforcing the communal bond.

Fasting was common, especially on Wednesdays and Fridays. The Christian calendar began to take shape, with the weekly celebration of Sunday as the Lord’s Day and the annual observance of Easter as the feast of Christ’s resurrection.

Charity and Daily Living

Perhaps the most striking aspect of early Church life was its charity. Christians cared for the sick, the widowed, the orphaned, and the poor—not just within their communities, but even among outsiders. Pagan observers noted this strange generosity, wondering why these people would care for strangers, or risk their lives during plagues to aid the sick.

Christianity also challenged social norms. It upheld the dignity of women, called slaves brothers and sisters, and emphasized chastity, faithfulness, and self-control. In a world driven by status, wealth, and pleasure, the Christian ethic was radical.

The Church became a counter-society, living by the values of the kingdom of God rather than the empire of Rome. Its people were called to be “in the world but not of it”—citizens of heaven who walked the dusty streets of Antioch, Ephesus, Carthage, and Rome.

Seeds of the Future

By the end of the third century, the Church had not only survived—it had grown. Despite sporadic persecution, misunderstanding, and internal struggles, Christianity had taken root across the empire. Its bishops were organizing into regional networks. Its Scriptures were being copied and read widely. Its martyrs were revered, its theology was deepening, and its moral vision was inspiring.

What began as a movement of fishermen and tax collectors had become a spiritual force that would, in time, reshape the Roman world.

And though no one in those darkened house churches could have foreseen it, just over the horizon lay a dramatic turn of history: an emperor would convert, persecution would cease, and the Church would step out from the shadows—forever changed.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Andes to Ireland: How the Potato Reshaped Global Agriculture

Egypt’s 18th Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of Its Greatest Pharaohs

15 Everyday Phrases with Surprisingly Medieval Origins

Why the Battle of Hastings (1066) Mattered

The Epic Italian Campaign: From Mussolini’s Downfall to the Liberation of Rome

Ulrich Zwingli: The Swiss Reformer Who Shaped Protestantism

379/8 BC: A Year of Intrigue and Shifting Alliances in Ancient Greece

How Did Czechoslovakia Become a Country?

Machiavelli, Luther, and the Rise of Modern Moral Thought

Arabia Felix: Exploring Ancient Hadramawt and the Port of Qana

Adam Smith: The Philosopher Who Revolutionized Economics

Roman Senate: Backbone —and Burden—of a World-Conquering Republic