The Transcontinental Railroad changed America. When it was finished in 1869, people and goods could cross the country in days instead of months. Towns grew. Prices fell. New jobs appeared. Behind this huge project stood a young engineer with a big dream: Theodore Dehone Judah. People called him “Crazy Judah” because he talked about the railroad all the time. But his vision and hard work helped make it real.

A Boy and a New Machine

Theodore Judah was born in 1826 in Bridgeport, Connecticut. At that time, the United States had only a few miles of railroad track. As Judah grew, so did the railroad industry. He studied civil engineering and, by 18, he was surveying tracks for the New Haven, Hartford & Springfield Line. At 21, he married Anna Pierce. She believed in his dreams and traveled with him as his work moved from place to place.

By the early 1850s, trains were the future. Cities wanted rail links. Investors wanted profit. In 1854, Judah got a life-changing offer: go to California and help build the first railroad in the American West. The governor of New York even recommended him for the job. California was full of gold money and big plans. A line that connected the West to the East could turn chaos into commerce. Judah said yes.

A Hard Journey West

There were two main ways to reach California from the East. You could cross the continent by wagon, or go by ship to Panama, cross the isthmus on foot or mule, then sail up the Pacific coast. Judah and Anna chose the Panama route. It was faster than sailing around South America, but the land crossing was tough and dangerous.

They reached Sacramento in May 1854. The city was booming but rough—saloons, gambling houses, and muddy streets. Judah got to work. Within two years, he helped build the Sacramento Valley Line, the first railroad west of the Missouri River. People began to call him “Crazy Judah.” He did not mind. He loved railroads and thought bigger than anyone else. He wanted a line that crossed the entire United States.

The Big Idea: A Railroad Across the Continent

A coast-to-coast railroad sounded simple. It wasn’t. The biggest barrier was the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Trains can’t climb steep slopes; they need gentle grades. In 1859, Judah went to Washington, D.C., to push Congress for a national railroad. Many leaders liked the idea, but they needed a detailed plan and a safe route.

Back in California, Judah searched for a path through the Sierras. In July 1860, a shopkeeper named Daniel “Doc” Strong from Dutch Flat wrote to him. Strong urged Judah to survey Donner Pass. Judah went—and found what he was looking for. Donner Pass had a steady rise and fall that a locomotive could handle. It was difficult, but possible. Judah and Strong teamed up. This choice of route later made the project feasible.

Finding the Money

Vision needs money. Judah and Strong raised about $46,000 from small investors in the gold fields, but that wasn’t enough. Then Judah met Collis P. Huntington, a tough businessman. Huntington had an idea: gather a small group of big investors instead of hundreds of tiny ones. He brought in Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker. People later called them the “Big Four.”

With their backing, the Central Pacific Railroad Company was born to build from California eastward. Judah kept pushing in Washington. In 1862, Congress passed a law (often called the Pacific Railroad Act) that gave loans, bonds, and land to help build the railroad. The national project was officially underway.

Dreams vs. Dollars

Soon, Judah and the Big Four clashed. Judah cared most about building a safe, well-engineered railroad. The Big Four cared most about profit. The government paid more for track laid in mountains than on flat land. Judah wanted honest measurements. The Big Four wanted to stretch the “mountain” miles. They overruled him, hired other surveyors, and controlled the company.

Frustrated, Judah looked for a way to buy them out and regain control. He hoped to raise money in the East from wealthy men like Cornelius Vanderbilt. If he could replace the Big Four, he believed the railroad would be built right and fairly.

A Sudden End

In October 1863, Judah and Anna left for New York. They took the Panama route again. On the crossing, Judah caught yellow fever, a deadly disease spread by mosquitoes. He grew weaker on the second ship north. When they reached New York, he was too sick to meet investors. One week later, he died at the Metropolitan Hotel. He was only 37. Anna buried him in Greenfield, Massachusetts.

Judah never saw the project finished. But he had given the railroad its route, its early momentum, and its political support. Without that foundation, the Transcontinental Railroad might have been delayed for years—or built somewhere far harder and costlier.

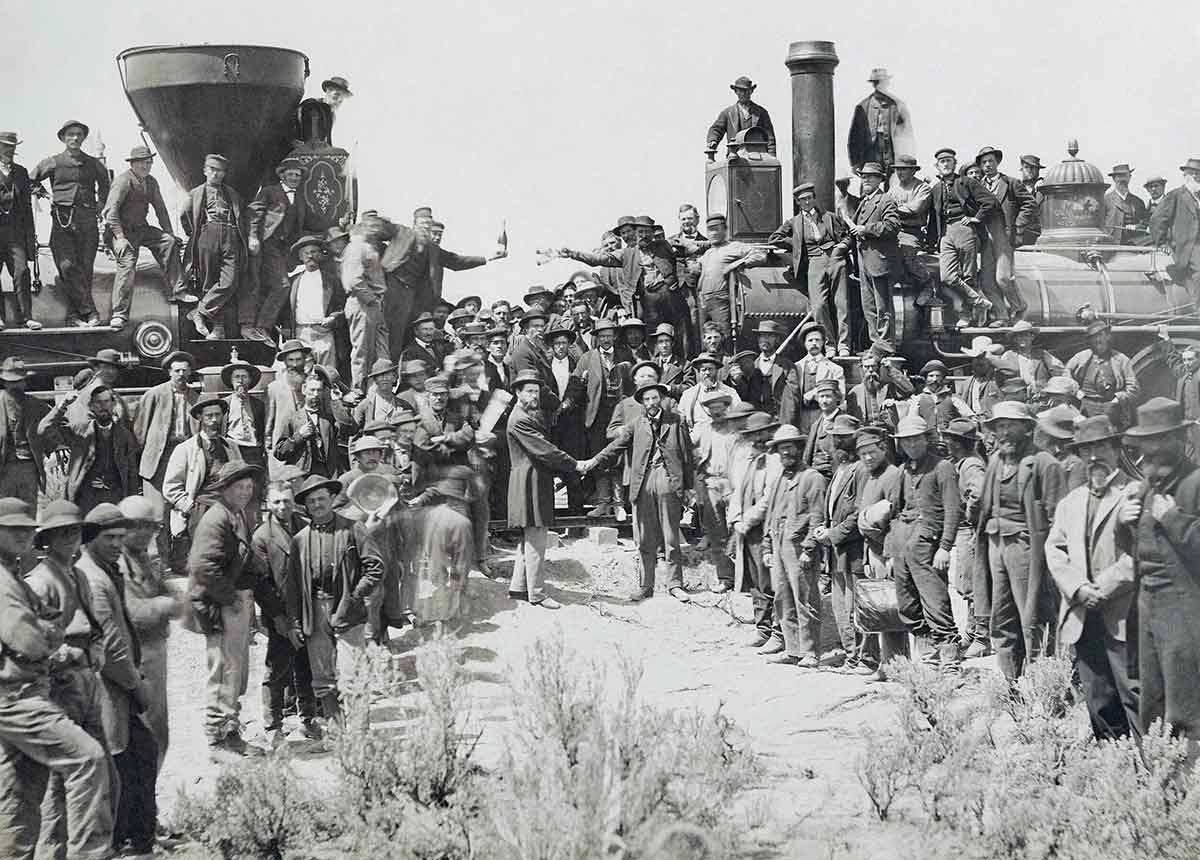

The Golden Spike

After Judah’s death, the Central Pacific built east from California while the Union Pacific built west from Nebraska. Crews blasted tunnels through granite, fought snowdrifts, and laid track across deserts. Chinese laborers on the Central Pacific did dangerous, relentless work for low pay. Progress was hard but steady.

In May 1869, the two lines met at Promontory Summit, Utah. Leaders hammered a ceremonial golden spike to mark the moment. Leland Stanford, one of the Big Four, swung the famous hammer. Telegraph wires carried the news nationwide: “DONE.” The journey from New York to San Francisco fell from months to about a week. America felt smaller, faster, and more connected.

Why Theodore Judah Matters

So why remember “Crazy Judah”? Because big national projects need more than money and muscle. They need a clear plan, a smart route, and someone who won’t let go. Judah believed a transcontinental railroad was possible when most people thought it was fantasy. He found the pass. He won early support in Congress. He gathered investors. He set the course.

Yes, others finished the job. Yes, some of them cut corners and made fortunes. But the spark—the idea with a workable path—was Judah’s. His “craziness” was simply the courage to see what did not yet exist and then do the hard things to make it real.

What This Railroad Did to America

- Cut travel time from months to days, changing how people moved and did business.

- Lowered costs to ship goods, helping farmers, miners, and manufacturers reach faraway markets.

- Created new towns along the route and sped up the settlement of the West.

- Tied the country together after the Civil War, making the United States feel like one connected nation.

These changes were not all good. Native nations lost land and freedom. Workers, especially Chinese laborers, faced harsh and dangerous conditions. But the railroad’s impact on the economy and national identity was enormous—and lasting.

A Simple Timeline to Keep It Straight

- 1826: Theodore Judah is born in Connecticut.

- 1854: Judah moves to Sacramento; helps build the first railroad in the West.

- 1860: Surveys Donner Pass; confirms a practical route over the Sierras.

- 1862: Congress passes the law to fund a transcontinental line; Central Pacific forms.

- 1863: Judah dies of yellow fever while trying to change the project’s leadership.

- 1869: The golden spike is set in Utah; the Transcontinental Railroad is complete.

The Takeaway

The Transcontinental Railroad was a bold bet on America’s future. It needed vision, engineering, money, and stubborn faith. Theodore “Crazy” Judah supplied the vision and the route. Others supplied the cash and construction. Together—through conflict, danger, and determination—they built the iron path that united a continent. Judah did not live to see the trains meet. But his fingerprints are on every mile.