Decolonization, like the empire-building that preceded it, is not a single story but a crowded crossroads—of people, tactics, languages, and imaginations. In the three decades after the Second World War, movements across Africa, Asia, the Pacific, and beyond turned uneven odds into unexpected victories. Many had little money, fewer weapons, and almost no international clout. What they did have was resolve—and a willingness to fight on more than one front at once.

Big Nations, Small Wars

By the mid-1970s, as the Vietnam War shuddered to its end, a political scientist named Andrew J. R. Mack gave a name to a phenomenon that the world had been watching unfold: asymmetric conflict—fights between unequals where conventional superiority does not guarantee victory. In his classic argument about “why big nations lose small wars,” Mack pointed to a truth insurgents understood intuitively: wars are not decided only by tanks, planes, and body counts. They hinge on political will—on the patience of the home front, the cost a government can bear, and the pressure exerted by global opinion.

Vietnam made that lesson vivid. The conflict unfolded on two intersecting stages: one violent and uncertain in the jungles and highlands of Indochina, and another—less bloody but arguably decisive—inside American politics, campuses, living rooms, and streets. The longer the struggle dragged on, the more it eroded the United States’ capacity and appetite to continue. In Mack’s phrase, insurgents worked toward “the progressive attrition of their opponents’ political capability to wage war.”

That dynamic had played out elsewhere too. In Algeria, a decade earlier, France’s military might could batter guerrillas, but not easily extinguish a society’s demand for sovereignty—especially once the global spotlight fell on the war’s brutality, and the costs of holding on mounted at home.

What Asymmetric Warfare Looks Like

Asymmetric warfare is, at heart, a wager on time. The weaker side trades rapid victory for a long campaign designed to exhaust and frustrate a stronger adversary. Hence guerrilla—Spanish for “little war.”

When outgunned, insurgents refuse the battle their enemy wants. Instead they:

- Stage ambushes and hit-and-run raids.

- Sabotage supply lines, bridges, power grids, airfields, and railways.

- Hijack or disrupt communications so reinforcements never get the call.

- Kidnap officials, destroy records, cut telegraph or fiber, and scatter the opponent’s attention.

- Feign retreats to lure troops into traps and then vanish into terrain or sympathetic communities.

The logic is simple: deny decisive engagement, impose constant cost, and make control so expensive that the occupier’s political coalition cracks. Even when the map doesn’t change, the balance of endurance does.

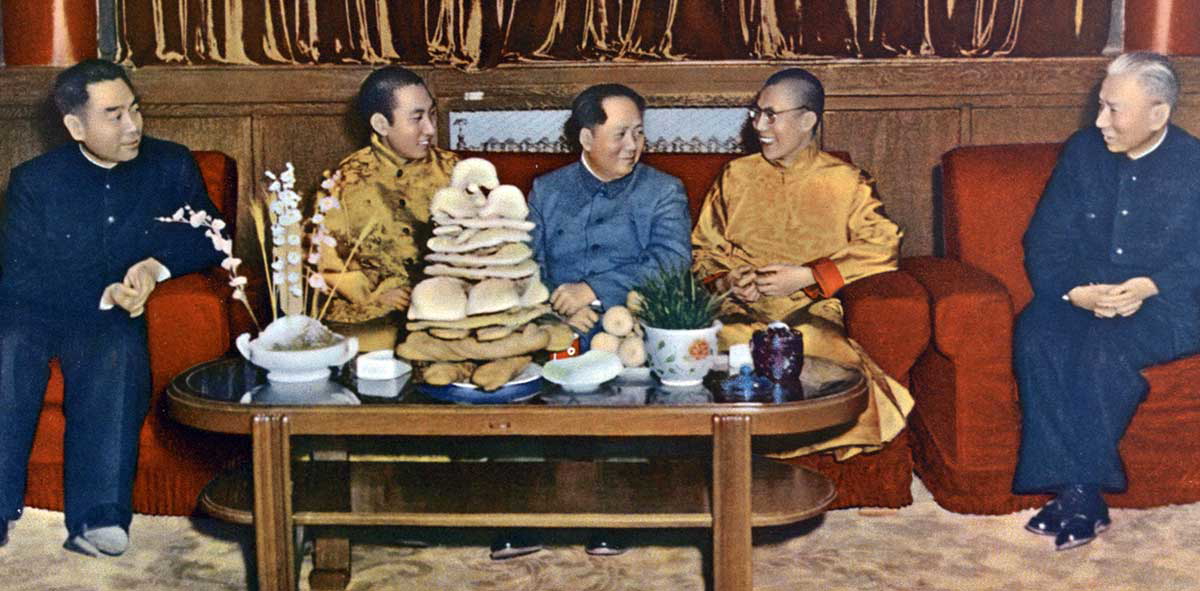

Mao’s Manual and the Art of Disappearing

Few thinkers shaped guerrilla doctrine more than Mao Zedong. In On Guerrilla Warfare (1937), he insisted that guerrilla struggle is not a stand-alone enterprise but a phase of a broader revolutionary war. It thrives on surprise, vigilance, deception, and speed. Most of all, it seeks to drain the enemy’s will to fight. His distilled advice remains a field guide for the outmatched: harass him when he stops; strike him when he is weary; pursue him when he withdraws.

Guerrillas wage war where their opponent is weakest: at the rear, the flanks, the overlooked node, the unguarded road at night. They study the rhythm of the occupier’s patrols, the habits of convoy drivers, the gap between orders issued and orders executed. They win time, then use time to win more ground—not of territory alone, but of public opinion and legitimacy.

This is why successful insurgencies are rarely purely military. They require networks—villagers who pass messages, traders who look the other way, students who print leaflets, artists who keep hope alive, elders who lend authority, and organizers who coordinate boycotts and strikes. The battlefield bleeds into the marketplace, the schoolyard, and the cinema.

More Stories

The War That Spilled Off the Battlefield

The Vietnam War made the two-front nature of asymmetric conflict unmistakeable. In the forests and mountains, a prolonged guerrilla campaign sapped American power; in the United States, a crescendo of anti-war activism chipped away at the political foundation of the war. Photographs on nightly news, the testimony of returning soldiers, and mass demonstrations reframed the conflict not as a crusade but as a quagmire. The same pattern—military stalemate paired with political erosion—had haunted France in Algeria.

Seen this way, asymmetric warfare becomes less a set of tactics than a theory of change: stretch the conflict until the cost of staying exceeds the shame of leaving.

The Quiet Front: Art Against Hegemony

If guerrillas pressured empires with ambushes and sabotage, artists and writers pressure them with stories. They contest the colonizer’s monopoly on meaning.

Senegalese filmmaker and novelist Ousmane Sembène captured it bluntly: if Africans do not tell their own stories, Africa risks disappearing from the world’s memory as a subject rather than an object. In his films and novels, the French colonial project is not abstract policy but daily indignity—experienced by dockworkers, market women, and children. He turns propaganda on its head, using the camera to insist on African complexity.

In Algeria, the writer Assia Djebar brought another kind of insurgency to the page. Her work chronicles women’s lives through the spasms of conquest and independence, refusing the simplistic images that once populated European accounts. On paper, as in the casbah, resistance meant refusing invisibility.

Across the globe in Aotearoa/New Zealand, the novelist Patricia Grace and others in the Māori Renaissance wove te reo Māori into English prose, opening a window onto a worldview long dismissed by the colonial mainstream. Their stories are not mere “representation”; they are acts of reclamation—evidence that a language, and the people who speak it, are vibrantly present.

The Australian author Alexis Wright poses unsettling questions at the heart of a settler nation: What do ancient foundation stories mean for modern literature? How do we write truthfully from a land layered with conquest? In asking, she binds literature to civic responsibility—a peaceful counterpart to guerrilla persistence, compelling societies to look, listen, and answer.

These creators do what insurgents do by other means: they deny indifference. Their work travels across borders and generations, building solidarity networks that make it harder for outsiders to pretend they do not see.

Language as a Weapon, and a Home

Empires rarely dominate by force alone. They also rule with grammar and vocabulary. To push back, decolonizing movements reclaim language as both a tool and a sanctuary.

Under French rule, Africa’s cinematic imagination was tightly policed—the notorious Laval Decree of 1934 made it nearly impossible for African directors in the colonies to make films at home. Yet with independence, Sembène would go on to film in Wolof, shattering assumptions about which tongues belonged on screens and who got to tell whose story. Language became an assertion of presence.

Djebar’s use of French—alongside the memory of Arabic and Tamazight (Berber)—exposes the intimate politics of expression. If the colonizer’s language tries to push others to the margins, writers can, in turn, bend that language to bear witness to what it tried to erase.

In Aotearoa/New Zealand, te reo Māori regained official status in 1987, a legal milestone that echoed a broader cultural resurgence. Authors like Patricia Grace and Witi Ihimaera lace English with Māori words and cadences, creating prose that sounds like the place it comes from. Ihimaera has written of a youthful resolve to “unpoison the stories” about Māori—a reminder that narrative is not neutral; it can wound, and it can heal.

On another island, Ireland, language bridged nonviolent and violent resistance alike. The Gaelic League, founded in the 1890s, sought to “de-anglicize” Ireland by reviving Irish as an everyday language. During the independence struggle, Irish served as both identity marker and shield—a code unknown to many British officials. Long after the gunfire faded, it remained a sign of continuity and community, especially in the north.

To write and speak in the languages empire tried to demote is to re-center the world. It is a pledge that children can grow up not merely translating themselves to be understood, but being understood as they are.

The Economics of Resistance

Guns and leaflets do not operate in a vacuum; they live in economies. Colonial power depends on extraction, bureaucracy, and the movement of goods. Anti-colonial strategy therefore often pairs guerrilla action with economic disruption.

Boycotts, general strikes, and tax refusals deny the colonial state the revenue and reliability it needs to function. Railway workers who sit down on the tracks, dock laborers who slow the loading of ships, shopkeepers who refuse to collect levies—all of them force an empire to pay attention. In places from Senegal to India, such mass actions created bottlenecks that military measures alone could not clear.

These tactics also do something subtler: they rehearse self-rule. Communities learn to coordinate, to improvise supply chains, to care for the vulnerable when salaries stop and the lights go out. Economic resistance is a school for citizenship.

Algeria and Vietnam: Case Studies in Endurance

In Algeria, the National Liberation Front (FLN) mixed classic guerrilla operations with urban bombings and international diplomacy. France could win skirmishes and hold cities, but each year of war intensified domestic strain. News reports, testimony about torture, and the sheer grind of deployment eroded public consent. Independence followed not from a single decisive battle but from the slow realization in Paris that the old calculus no longer added up.

In Vietnam, the United States possessed overwhelming firepower. Yet the North Vietnamese and National Liberation Front offset that advantage by dictating the terms of engagement, dispersing into terrain, and keeping a political drumbeat that made the war feel endless and unwinnable to distant voters. The conflict’s “second front” in American society—student marches, draft resistance, veterans’ voices—transformed the question from Can we win? to What does winning even mean, and at what cost?

Both struggles underline a principle of asymmetric war: victory is not control of a hill but control of the horizon—of what each side believes is possible six months from now, and what it is willing to sacrifice to get there.

Culture as Counter-Occupation

Armed struggle can drive out troops; culture keeps them from returning in spirit. In Algeria, as soldiers fought, Djebar and other intellectuals chronicled women’s experiences and mapped the contours of a changing society. Their work pushed back against stereotypes that survived long after flags changed.

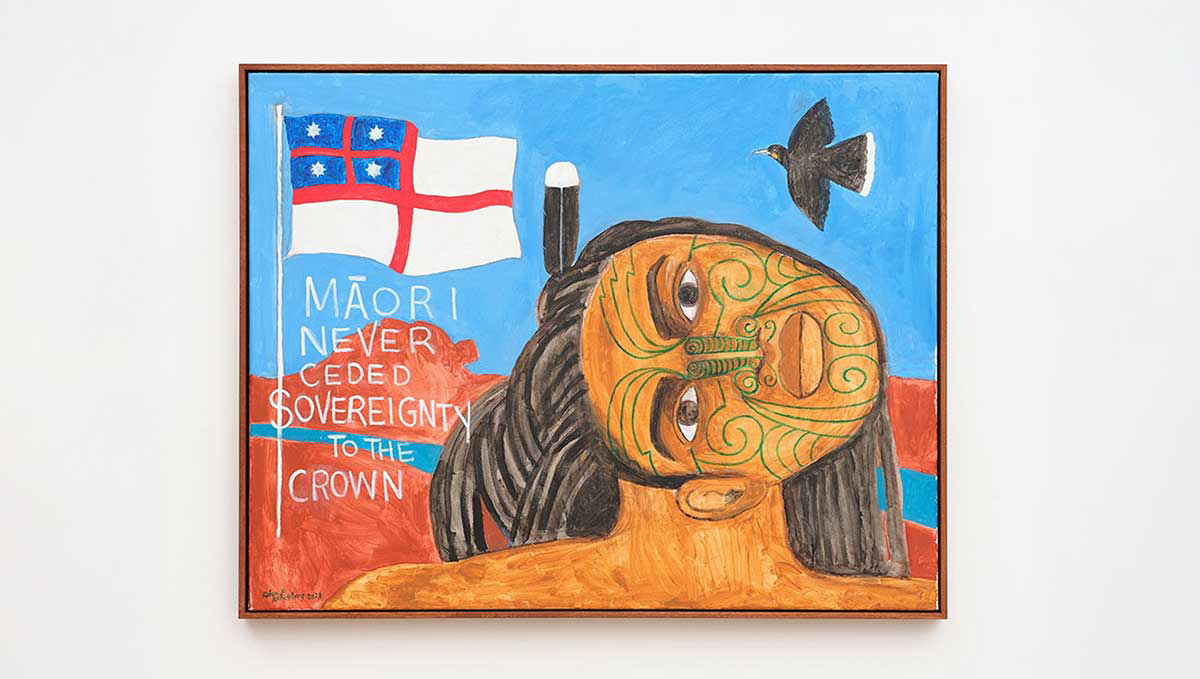

In Australia, Alexis Wright speaks to the foundational fracture of a nation built on the dispossession of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Her call for “truth telling” does not merely revise a syllabus; it reorients a public toward responsibility. In New Zealand, the recognition of te reo in law and literature plants roots where colonization once tried to salt the earth. Meanwhile, Māori visual artists—like Robyn Kahukiwa, whose paintings braid human figures with words of te reo—make canvases into memory palaces, places where a people can see themselves whole.

Culture does not topple regimes by itself. But it changes the weather in which politics happens. It turns private grievance into public knowledge. It teaches future leaders what words feel like in their mouths.

The Two Fronts, Together

When we zoom out, the pattern is plain. The military front—ambushes, sabotage, raids—aims to raise costs and lower confidence. The cultural-linguistic front—novels, films, poetry, language revival—aims to make disappearance impossible, to assert presence so persuasively that even opponents start using new terms and frameworks.

The genius of many decolonization movements lies in how these fronts reinforce each other. A strike cuts rail traffic and gives a filmmaker a scene. A pamphlet echoes on a radio broadcast, which emboldens villagers to harbor fighters. A poem becomes a song becomes a march becomes legislation. Slowly, the colonizer’s sprawl looks less like inevitability and more like a choice that can be unmade.

Climax: Breaking the Spell of Inevitability

Empires thrive on the aura of permanence—the sense that their maps are the map and their language the language. Asymmetric struggle breaks that spell.

Consider a month in which a patrol is ambushed, a bureaucrat resigns, a strike halts a port, a writer wins a prize for a novel in a language once banned, and a mural goes up in a capital city celebrating heroes the empire never meant to name. None of these events is decisive alone. Together they recompose reality. The empire can no longer claim to speak for the future.

For those on the ground, this is not abstract theory. It’s the daily work of endurance—keeping courage when water is scarce and the curfew loudspeakers crackle, when a child asks you why they can’t speak their grandmother’s language at school, when the world seems to move on. Decolonization advances in those moments too, not just in dramatic set pieces, but in the stubborn decision to go on telling the story.

After the Flag Comes Down

Independence ceremonies are powerful, but they are not the end. Languages need funding, schools, and air time. Archives must be opened. Land claims must be heard. Veterans must be welcomed home into economies strong enough to sustain them. The transition from insurgency to governance can be perilous: the habits that help a movement survive in hiding are not always the ones that build transparent states.

Here again, culture matters. Films, novels, and songs do not merely celebrate victory; they warn and teach. They ask whether a new nation will replicate old hierarchies, whether women and minorities will see their liberation honored, whether the wounds of war will be acknowledged. The next generation learns its history not only from textbooks but from the voices of those who lived it.

Conclusion: The Long Work of Freedom

Decolonization is the art of making possibility outlast power. It draws on patience, improvisation, and solidarity. It is fought with roadside bombs and with bilingual books, with whispered passwords and public festivals, with night raids and daylight truth telling. No single tactic carries the day. What wins is the weave—the way guerrilla persistence, economic noncooperation, and cultural renewal knot together into a rope strong enough to pull down an empire.

In the end, asymmetric warfare’s greatest insight extends beyond the battlefield: people can change the terms of the argument. When the colonized insist on their names, their languages, their stories, and when they refuse to be lured into the fight the empire wants, they tilt the horizon. The lesson of the mid–twentieth century is not that the weak always win, but that they sometimes do—and when they do, it is often because words and deeds marched in step.

The work is unfinished. It always is. But every time a child learns the grammar of an ancestor’s tongue, every time a community refuses a tax designed to exploit them, every time an artist puts resistance on a screen or a page, the future moves a little. The spell of inevitability cracks. And freedom, so often imagined as a sudden dawn, turns out to be something else: a sunrise you help paint, stroke by patient stroke.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

King Octa of Kent and the Clockwork of Arthur’s Age

The Enduring Unity and Adaptability of Christian Morality

The 3 Battles That Decided the Franco-Prussian War

Suez Canal: From Ancient Dream to Present Reality

Inside a Japanese Castle

Thanksgiving, Politics, and the Quakers

Political Theme in Every History Tales

The Largest Urban Centers in Medieval Times

Arsinoe IV: Cleopatra’s Forgotten Rival

Vortigern: The Controversial King of Post-Roman Britain

Diocletian and Constantine: On the Threshold of the Fourth Century

Why the Battle of Hastings (1066) Mattered