In the stories we tell about Rome, the stage is crowded with men—generals, senators, emperors—while women hover at the margins, embroidered into the background like laurel and thunderbolts. Yet sometimes the background becomes the whole tapestry. When Livia Drusilla married Octavian—soon to be Augustus—she stepped into a new role the world had never seen before: the first Roman empress.

To some contemporaries, she was the ideal matron—chaste, dignified, provident. To later historians, she became the quintessential schemer, a mother who would salt the earth with poison to see her son on the throne. Between those warring portraits lies a life more complicated and more human: a young refugee of civil war, a political bridge-builder, a household sovereign, a lightning rod for rumor—and finally, Diva Augusta, worshiped beside Rome’s first emperor.

This is Livia’s story—storm-tossed youth, unconventional marriage, serene ideal, and the shadows that stalked her fame.

Civil War and a Girl on the Run

Livia Drusilla was born on January 30, sometime between 59 and 57 BCE, into the sternly prestigious Claudian line. Her father, Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus, stood with the assassins of Julius Caesar. In the furnace of Rome’s civil wars, this allegiance would scorch his daughter’s early life.

At about 15 or 16, Livia married her older cousin, Tiberius Claudius Nero, a man already on Rome’s cursus honorum: praetor in 42 BCE, meaning he was roughly forty when he wed the teenaged Livia. She swiftly bore a son—Tiberius—in that same year. But politics would not leave them in peace. Nero first sided with Mark Antony, then Sextus Pompeius, and finally fled Octavian’s rising power for Greece. Livia followed—a young mother with a child in her arms, a political refugee before the man who would soon rule the world.

In 39 BCE, an amnesty opened the city’s gates. Livia and her husband returned to Rome. She was pregnant again.

What happened next would become one of Rome’s most sensational social maneuvers.

A Hasty Wedding

The sources say Octavian met Livia and was smitten. The most powerful man in Rome divorced Scribonia the very day she gave birth to his only biological child, Julia. At the same time, Tiberius Claudius Nero was persuaded—“like a father,” the accounts stress—to divorce Livia though she was late in pregnancy. Livia delivered Drusus on January 14, 38 BCE and married Octavian three days later.

Why the haste? Passion is one answer. Politics is another. Rome was exhausted by civil war; Augustus needed to stitch together a fractured nobility. Livia’s Claudian ties—and her former husband’s networks—were valuable threads. The marriage also carried a whisper of omen—the tale of an eagle dropping a white hen with a laurel sprig into Livia’s lap—a sign, people said, of fertility and victory.

The union looked, at first, like a dynast’s dream: Octavian sought sons; Livia had already borne two. Fate disagreed. Livia’s first pregnancy by Octavian ended in stillbirth and complications left her infertile thereafter. Yet the marriage endured—for 51 years. Whatever its origin—romance, reason, or both—it held.

If you need a modern shorthand: it’s a Bridgerton season penned by Tacitus—courtship, alliance, a dazzling wedding…and a lifetime of consequences.

The Model Matron

With Octavian’s transformation into Augustus in 27 BCE, Livia’s public role crystallized. She became the empress before the title existed, the face of Augustus’s moral program. On the Palatine, she ran a household that was luxurious without excess. She dressed elegantly but avoided vulgar display, reportedly weaving garments by hand—a symbolic nod to old Roman virtue. The message was clear: as Augustus remade the state, Livia remade the household—Rome’s smallest state.

Not that she was cloistered. Augustus granted her control over extensive property—from copper mines in Gaul to palm groves in Judea—and she used that wealth for philanthropy: fire relief in Rome, dowries for impoverished girls, support for clients who would seed future imperial circles (among them the ancestors of emperors Galba and Otho). Ambassadors courted her favor; petitioners sought her intercession. The philosopher Philo would praise her “masculine intellect,” by which he meant—without irony—capacities Roman writers coded as male: prudence, foresight, reason.

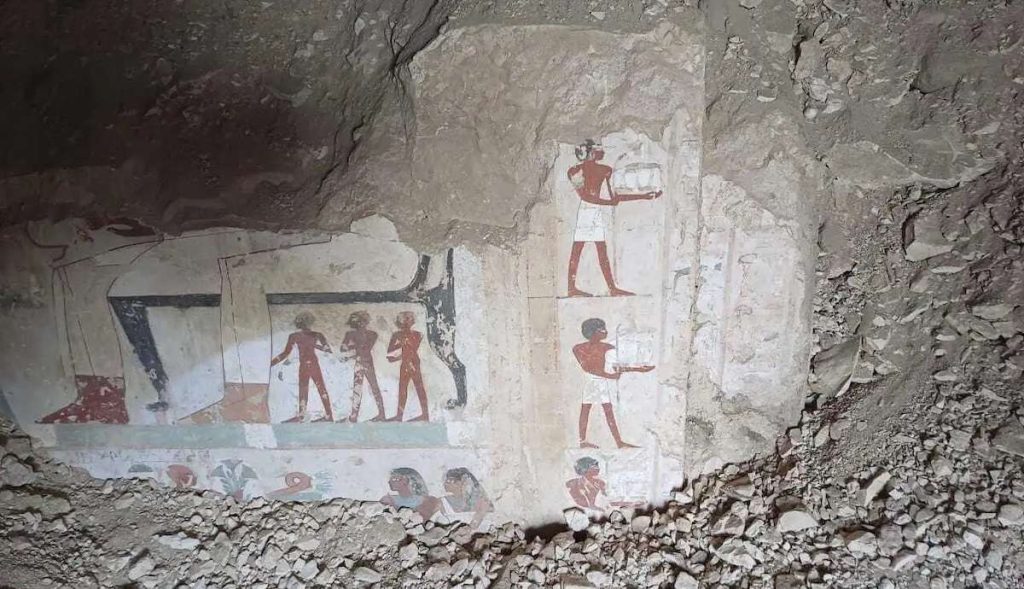

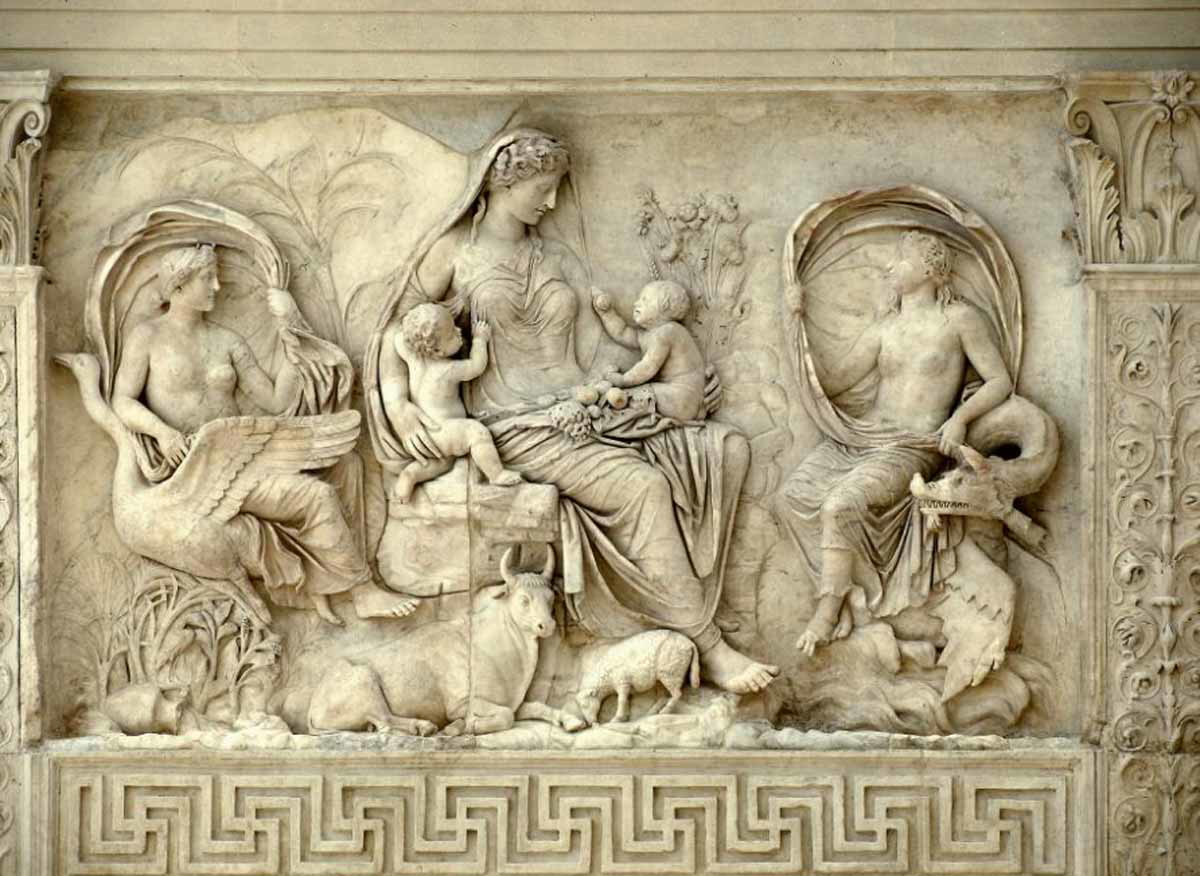

The state recognized the symbolism. On January 30, 9 BCE, the Ara Pacis—altar of Augustan peace—was dedicated on Livia’s birthday. Its processional reliefs parade the imperial family as the family of Rome. At the center, Livia serves as the visual hinge between dynasty and citizenry; on the mythic panels, a maternal goddess nurses twin infants—Pax, perhaps, but to Roman eyes, also Livia’s archetype: the mother who nourishes the state.

This was the public Livia: modest yet mighty, matron and mediator, the empire’s velvet glove.

The Birth of a “Murderous Mother”

History cannot resist whisper campaigns, and ancient Roman history least of all. While friendly pens like Velleius Paterculus extolled Livia’s virtues, later authors—above all Tacitus and Cassius Dio—recast her as a woman capable of any crime to advance her son Tiberius.

The accusations read like a poisoner’s calendar:

- 23 BCE: Augustus’s young heir, Marcellus, dies of illness. Later rumor: Livia killed him because he eclipsed her sons.

- 12 BCE: The emperor’s right hand, Agrippa, dies on campaign. Not her doing, say the sources—yet the dynastic board shifts.

- 2 CE: Lucius Caesar, grandson and adopted son of Augustus, dies after a riding accident.

- 4 CE: Gaius Caesar, his brother, dies of campaign wounds. Tacitus alleges that “untimely fate, or the treachery of their stepmother Livia,” removed both.

There’s more. Julia, Augustus’s only child, was exiled in 2 BCE for flagrant adultery and possible politicking. Some claimed Livia pushed the sentence out of resentment; equally, Augustus was publicly incensed by Julia’s mockery of his moral laws and needed no shove.

The darkest rumor comes last: that Livia poisoned Augustus himself—fresh figs smeared with venom—to smooth Tiberius’s succession. But Augustus was elderly and ailing; Tiberius was already the clear heir. The motive is feeble, the story theatrical.

If any death lies plausibly in Livia’s shadow, it is that of Agrippa Postumus, Julia’s last son, killed just after Augustus died but before the public announcement—removing a volatile claimant. Even here, the picture blurs: Agrippa Postumus had been exiled for violence and instability years earlier; some ancient reports say Augustus himself ordered his execution in the event of his death to forestall civil war.

More broadly, note the timeline. The fiercest portraits of Livia as murderous matriarch were penned after Nero’s fall, when writers looked back through the lens of Agrippina the Younger—a very real schemer and possible poisoner. Livia became the template retrofitted to a stereotype: the dangerous empress-mother.

What do we know, then? That people died—in war, by accident, from illness—in a world without antibiotics and with hard saddles. That a few deaths were politically convenient to Tiberius. And that a woman at the center of power is easily crowned culprit by hindsight.

More Stories

The Dowager Empress

When Augustus died in 14 CE, Livia did not recede. She advanced—carefully, publicly.

- Augustus’s will adopted her into the Julian gens; the Senate heaped honors upon her, and she took the title Augusta as Tiberius became Augustus.

- She was granted a lictorial escort—a symbol of magistrate power—and sat among the Vestal Virgins at public events, a startling elevation for any Roman woman.

- As priestess to the deified Divus Augustus, she stood at the threshold between state and cult.

Tiberius, austere by temperament and mindful of his adoptive father’s warnings, tried to trim the excess—refusing, for instance, the paired titles pater patriae for himself and mater patriae for his mother. But Livia’s soft power proved resilient. She received ambassadors, signed agreements with client kings, and—when Tiberius withdrew to Capri in 26 CE—she and the praetorian prefect Sejanus helped manage the empire’s daily choreography. Sejanus’s eventual overreach and execution, after Livia’s death, hints that it was her gravity as much as Tiberius’s suspicion that kept Rome’s most dangerous courtier in orbit.

Again, the rumor mill churned. Livia supposedly engineered the suffocating of Germanicus, Tiberius’s adopted son and the people’s darling, via the proxy Piso. The trial ended with Piso’s suicide, not a murder conviction; Germanicus had been an uneven general and ailing. The simplest reading remains the best: no proof ties Livia to the deed, and Germanicus’s sons—Nero, Drusus, and Gaius (Caligula)—continued, for a time, to be groomed within the imperial household. Livia herself looked after Caligula, who lived with her until she died.

Death, Memory, and a Woman Made Divine

Illness came for Livia in 22 CE; Tiberius hurried to her bedside. When she fell ill again in 29 CE, he did not return. She died at roughly eighty-six, and her funeral oration was given by Caligula, not her son. Was Tiberius estranged? Or simply unwilling to reenter Rome’s political theatre? Ancient sources, as usual, supply more attitude than certainty.

The Senate proposed divine honors. Tiberius blocked them, claiming to follow her wishes—perhaps truly, perhaps out of his reflexive caution. Caligula, on becoming emperor, announced he was fulfilling Livia’s will where Tiberius had not; notably, this did not include deification. The signal seems consistent: Livia expected mortal honors.

And yet divinity found her. When Claudius unexpectedly rose to the purple in 41 CE, he needed to stitch himself convincingly into the Julio-Claudian fabric. Livia was his grandmother. Claudius deified her as Diva Augusta and placed her as co-recipient of worship in the temple of Divus Augustus. From then on, priestesses and Vestal Virgins tended her cult; sacrifices were offered for the safety of the imperial house in her name.

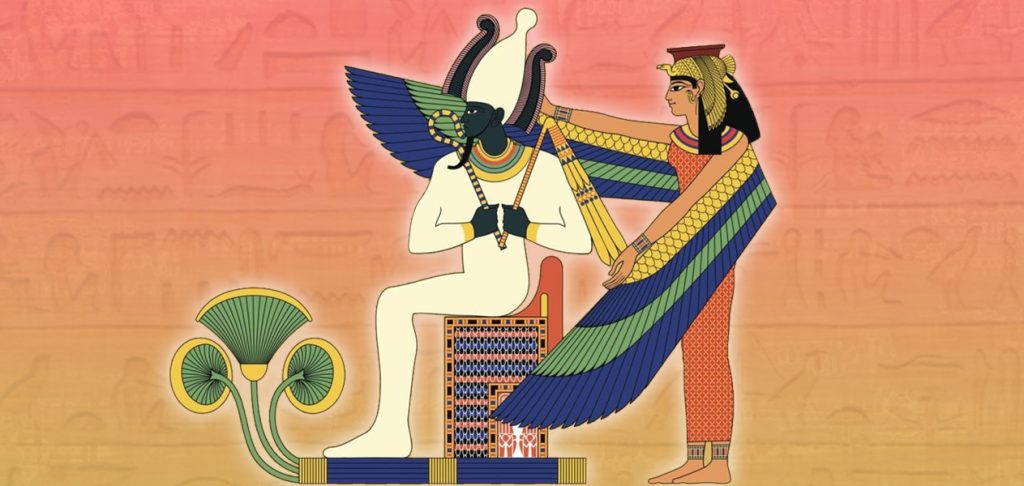

This formal apotheosis only confirmed what had long been true in practice. In domestic shrines across Italy and the provinces, heads bowed daily to the genius of the emperor and the juno of his empress. Ovid, exiled to the Black Sea, wrote of the silver figurines of Divus Julius, Augustus, and Livia in his household altar, recipients of his yearning prayers. Provincial cities paired temples to Roma and Augustus with statues and feast days for Livia; in the province of Asia, her birthday was celebrated alongside Augustus’s. Even before the Senate said “divine,” everyday Romans had already felt it.

Legacy

Livia built an invisible office. There was no constitutional role for an empress; there was only what the emperor allowed and what the public would accept. She defined the balance: persuasive but not overtly political; charitable yet powerful; central to dynastic reproduction without seeming to rule through the household. When successors obeyed that balance—Antonia Minor, Livia Orestilla, Plotina, centuries later Sabina—they were praised as models. When they didn’t—Messalina, Agrippina the Younger—they were vilified with Livia’s borrowed sins.

Genealogically, her influence is astonishing. She alone connected the first dynasty’s peaks and troughs:

- Wife of Augustus

- Mother of Tiberius

- Grandmother of Claudius

- Great-grandmother of Caligula

- Great-great-grandmother of Nero

If the Julio-Claudians are a vine, Livia is the trellis—the quiet structure that let power climb.

Ideal or Monster?

Was Livia the ideal matron who wove garments and peace in equal measure? Or the ruthless mother who salted figs with poison? The archive earns no such clarity. We know she navigated exile, brokered alliances, managed wealth, patronized the needy, advised emperors, and sustained a dynasty through fifty-one years beside the princeps and fifteen more as Augusta.

We also know that a woman who moves levers is easy to slander in eras that hate to see her hands on the machine. In the end, the most generous reading and the most realistic one converge: Livia was capable. She loved her sons, guarded her household, and believed in the state her husband built. She understood Rome’s theater and played her role with controlled grace—never quite center stage, yet with a presence that made the drama possible.

As long as Rome tells stories about its first household, Livia will be there: sometimes a halo, sometimes a shadow—but always the mother of the empire.

Quick Facts

- Born: January 30, 59–57 BCE

- Marriages: Tiberius Claudius Nero (43–38 BCE); Octavian/Augustus (38 BCE–14 CE)

- Children: Tiberius (emperor), Drusus (general) by her first husband

- Public Role: Ideal matron, property owner, philanthropist, imperial intermediary, priestess of Divus Augustus

- Titles: Augusta; later Diva Augusta (deified by Claudius)

- Died: 29 CE, age ~86

- Legacy: Template for the empress; ancestress to Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero