For more than 3,000 years, the Egyptians turned everyday life into a conversation with the divine. Their faith shaped pyramids and poetry, daily chores and dynastic wars. Yet Egyptian religion never stood still. It morphed from village animism to state-sponsored theology, then blended with Greek philosophy before Rome swept in. This post traces that restless evolution, decade by decade, showing how new gods, foreign rulers, and social upheaval kept reshaping the spiritual landscape.

📜 Predynastic Roots (c. 6000–3100 BCE): Tribal Spirits and Totems

Long before pharaohs, Nile farmers worshiped local forces they could see and fear: the flood, the desert edge, and animals who thrived in both. Each nome (province) had its own guardian beast — a falcon in Upper Egypt, a cobra in Lower Egypt. Shrines were simple reed huts, but wall paintings already showed processions that look like miniature temple rituals.

Highlights

- Fetish poles and animal standards carried in community festivals foreshadowed later divine processions.

- Early symbols — the lotus, papyrus, and Bennu bird — survived millennia, proving how sticky religious images can be.

📜 Early Dynastic & Old Kingdom (c. 3100–2181 BCE): The King as High Priest

When Narmer unified Egypt, the pantheon unified too. Local deities were bundled beneath state god Horus, whose earthly avatar was the pharaoh. Large stone temples appeared alongside mastaba tombs, funded by grain tax and staffed by hereditary priesthoods.

Key Changes

- Cosmic Bureaucracy — Gods acquired court titles (vizier of the north wind, overseer of granaries), mirroring human government.

- Pyramid Texts — First devotional writings carved in royal tombs, promising the king a place among the stars.

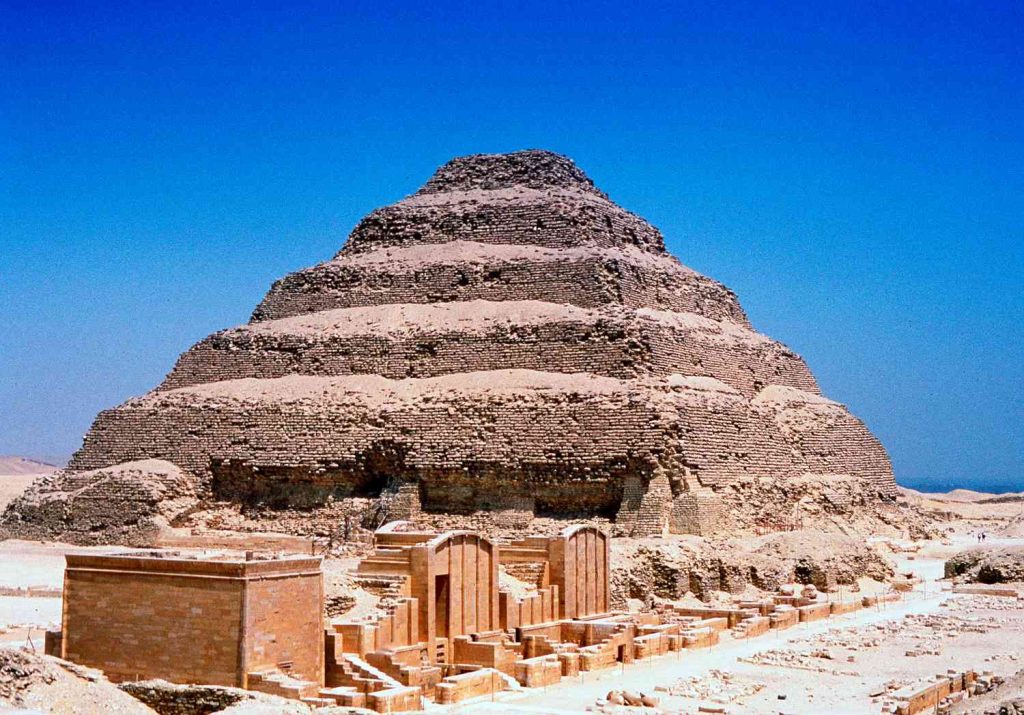

- Architectural Theology — Pyramid shape echoed the primeval mound of creation; its polished casing reflected the sun god Ra.

📜 First Intermediate Period & Middle Kingdom (c. 2181–1650 BCE)

Civil war toppled the Old Kingdom’s divine monarchy. Local rulers revived provincial cults; ordinary people could now commission coffin spells once reserved for royalty. The god Osiris—murdered, resurrected, and merciful—replaced the distant solar king as afterlife judge.

Why It Mattered

- Coffin Texts: spells individualized; a middle-class family in Thebes could buy cosmic insurance.

- Personal Piety: stelae show villagers praying directly to deities, bypassing temple priests.

Image suggestion 4 (right-aligned): painted wooden coffin with Book of the Dead vignette.

Caption: “Spell 125: Your heart testifies, not your birth rank.”

📜 New Kingdom Splendor (c. 1550–1069 BCE)

Flush with tribute from Nubia and Syria, Egypt built temple-cities such as Karnak and Luxor. Two religious currents collided:

- Amun-Ra Syncretism — The once local wind god Amun fused with the solar Ra, becoming king of gods.

- Atenism — Pharaoh Akhenaten shut other temples and preached exclusive worship of the sun’s disk (Aten). His revolution lasted just 17 years but left stunning art and theological shockwaves.

Everyday Devotion

- Pilgrims journeyed to Opet festival, cheering barque floats on the Nile.

- Household shrines held clay figurines of fertility goddess Taweret and dwarf god Bes for childbirth protection.

📜 Third Intermediate & Late Period (c. 1069–332 BCE): Foreign Rule, Local Resilience

Libyan warlords, Nubian pharaohs, Assyrian invaders — Egypt’s throne spun like a revolving door. Yet temples mushroomed, and priests of Amun sometimes rivaled kings in power.

Notable Trends

- Animal Cult Boom: Mummified cats, ibises, and crocodiles offered affordable devotion.

- Rise of Isis: Her promise to help anyone, anywhere made her a superstar beyond Egypt.

- Oracle of the Dead: Popular pilgrimages to speak with deceased relatives show a shift toward emotional spirituality.

Image suggestion 6 (left-aligned): rows of cat mummies at Saqqara.

Caption: “Five million feline votives — faith could be furry.”

📜 Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)

Alexander’s generals adopted Egyptian divinity: Ptolemy I declared himself son of Ra and created the hybrid god Serapis (Zeus + Osiris). Greek became temple lingua franca; priesthoods mastered Hellenistic philosophy to justify ancient rituals.

Cultural Fusion

- Isis & Serapis Abroad: Temples sprang up in Delos, Rome, even London.

- Egyptian Horoscopes: Babylonian astronomy merged with Egyptian star lore, birthing personal horoscopes on papyrus.

📜 Roman & Early Christian Egypt (30 BCE–400 CE): Twilight of the Old Gods

Rome taxed temples heavily yet kept priests on the payroll, seeing them as local administrators. But new competition arrived:

- Mystery Cults — Mithras, Cybele, and Isis each vied for converts in cosmopolitan Alexandria.

- Christianity — Introduced by Mark the Evangelist (traditionally), it appealed to the poor with a relatable martyr-god and universal salvation.

Key Moments

- Edict of Milan (313 CE) legalized Christianity; desert monks repurposed abandoned temples as monasteries.

- Isis’s Last Stand — Her temple at Philae stayed open until 537 CE, the empire’s final pagan sanctuary.

📜 Core Themes Behind the Changes

| Century | Catalyst | Religious Response | Lasting Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Dynastic | Political unification | State god Horus elevated | Pharaoh = divine king |

| First Intermediate | Civil collapse | Osiris democratizes afterlife | Personal coffin spells |

| New Kingdom | Imperial riches | Amun-Ra supersedes others | Monumental temples |

| Amarna | Royal ideology | Atenist monotheism | Artistic naturalism |

| Late Period | Foreign rule | Local cult revival, animal mummies | Mass-market devotion |

| Ptolemaic | Cultural fusion | Serapis, Isis abroad | Mediterranean popularity |

| Roman | Imperial policy | Gradual Christianization | Pagan temples repurposed |

📜 How Ordinary Egyptians Practiced Their Faith

Even while doctrines shifted, three constants bound Egyptian spirituality:

- Offerings — beer, bread, incense, or a clay cat were tickets to divine favor.

- Maʿat — the cosmic balance; whether praying to Ra or Christ, Egyptians still prized harmony.

- Storytelling — myths retold at harvest festivals linked daily toil to cosmic drama.

📜 Legacy: Echoes in Modern Spirituality

Today, Wiccans invoke Isis, architects borrow pyramid symbolism, and pop culture reimagines Anubis as a comic-book hero. Egypt’s religious journey shows how belief systems grow by absorbing rather than erasing what came before. Even Christianity in Egypt adopted the ancient ankh as a Coptic cross variant.

Ancient Egyptian religion was never a monolith entombed in stone; it was a river, like the Nile itself — changing course, flooding with new silt, yet always life-giving. From local animal spirits to cosmic sun disks, from secret hymns of Isis to Coptic chants, Egyptians kept updating their toolkit for making sense of life, death, and the hereafter. Their story reminds us that the sacred is a moving target, shaped as much by politics and trade as by visions of the afterlife.

When you stroll past a pyramid-shaped skyscraper or wear the Eye of Horus on a necklace, you’re part of that living current.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Five Descartes Quotes That Still Sharpen Your Mind

How American Lend-Lease Trucks Fueled the Soviet War Machine in WWII

5 Legendary Kings Who Built Thailand: From Sukhothai to the Chakri Dynasty

Why the Battle of Hastings (1066) Mattered

New Year, Old Books: A Tradition of Book Giving

Sir Thomas More: Why He Became Tudor England’s Most Controversial Man

North African Campaign: Fire on the Desert

Was King Charles I England’s Worst Monarch?

Zarathustra: The Prophetic Visionary Behind Zoroastrianism

Plato’s Gorgias: Rhetoric, Morality, and the Pursuit of the Good Life

How French Became the Language of Power and Prestige

Peter (Simon) of the Twelve Disciples: The Rock of Faith and Redemption