From the very beginning, humans have asked the same big questions:

Where did the world come from? Why are we here? What holds everything together?

Long before science, people answered those questions with creation myths – powerful stories that explained how the universe began and how humans fit into it. These myths weren’t just entertainment. They helped justify social order, define humanity’s role, and give meaning to life.

What’s fascinating is that when you compare creation stories from all over the world, many of them fall into a few recurring patterns. Different cultures, different gods – but surprisingly similar story structures.

Here are five of the most common types of creation myths, and what they reveal.

1. Creation from Chaos

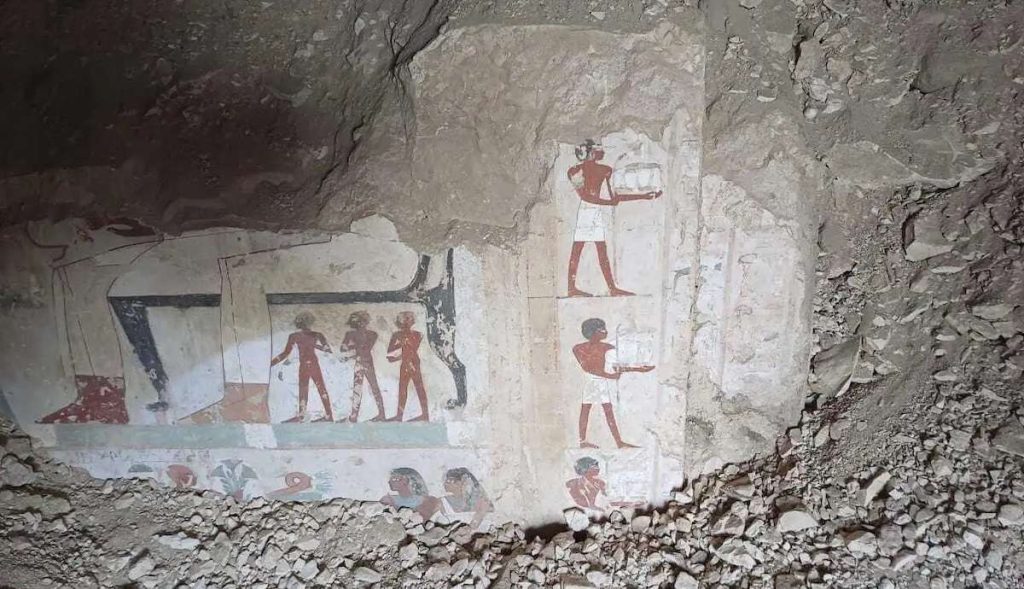

One of the oldest and most widespread patterns starts with chaos – a shapeless, formless “before-time.”

In these stories, the world doesn’t begin with order, but with disorder:

- a dark, watery abyss

- a swirling void

- raw, undifferentiated matter

Out of that chaos comes a struggle that brings structure: sky versus earth, gods versus monsters, light versus darkness.

The Babylonian Example: Marduk and Tiamat

In the Babylonian epic Enuma Elish (around 1200 BCE), the universe begins as a mixture of fresh water (Apsu) and salt water (Tiamat), both personified as gods. From them, other gods are born, and soon there is conflict.

The storm god Marduk rises as a hero. He fights Tiamat, defeats her, and splits her body in two:

- one half becomes the heavens

- the other becomes the earth

Creation here is not gentle. It’s the result of violence and victory. The Babylonians recited this story every spring at the Akitu festival, renewing the world symbolically by retelling the victory of order over chaos.

The Greek Version: From Chaos to Olympus

Greek mythology offers a similar pattern. The poet Hesiod describes an initial state called Chaos – a kind of gap or void. From Chaos come:

- Gaia (Earth)

- Eros (Love)

- Tartarus (the underworld)

Gaia gives birth to Uranus (Sky) and the Titans. Later, the younger Olympian gods, led by Zeus, overthrow the older Titans and establish a new, more just divine order on Mount Olympus.

Again, we see the same arc:

chaos → birth of primal forces → generational conflict → a new, improved order.

2. World Parents: Sky Father and Earth Mother

Another common pattern is the World Parent myth: the idea that the universe begins with a Sky Father and Earth Mother, whose bodies literally make up the world.

In these stories, the two original beings are often locked together, with their children squeezed in the darkness between them.

The Māori Story of Rangi and Papa

In Māori tradition from New Zealand:

- Rangi is the Sky Father

- Papa is the Earth Mother

They cling tightly to each other, their embrace so close that no light and no space exist between them. Their children – gods of forests, winds, and seas – live trapped in darkness.

Longing for space and light, the children try to push their parents apart but fail. Finally, the forest god Tāne-mahuta manages to separate them by bracing his shoulders against Papa and pushing Rangi upward with his powerful legs.

In that moment:

- the sky lifts

- the earth lies beneath

- the world fills with air and light

Even today, the rain is said to be Rangi’s tears for Papa, and the mist is Papa’s sighs for Rangi. The myth explains both the shape of the world and the deep emotional bond built into it.

3. Underground Origins: Emerging from Earlier Worlds

Some creation stories don’t begin with a god shaping the world from outside, but with humanity climbing up from somewhere below.

This pattern is especially common among some Native American peoples, particularly in the Southwest.

The Hopi Journey Through the Worlds

In traditional Hopi belief, humans didn’t always live in the current world. Instead, they passed through three previous underground worlds:

- In each earlier world, people became corrupt.

- Their bad behavior eventually led to that world’s destruction.

- A small group of good people survived and moved upward.

After the third world was ruined, a handful of righteous people were guided up through a hollow reed into the fourth world – the world we live in now.

For the Hopi, this story is not just about origin, but responsibility. Because they emerged into this world and were given another chance, they see themselves as having a sacred duty to care for the land and maintain balance.

4. The Earth-Diver: Land from the Depths

Another widespread pattern, especially among peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands and elsewhere in North America, is the Earth-Diver myth.

These stories also begin with a world covered in water, with no solid ground at all.

Sky Woman and the Muskrat

In many Iroquois versions, the story begins in a sky world. A woman—often called Sky Woman—falls from that realm and descends toward the endless ocean below.

Instead of drowning, she lands gently on the back of a great turtle, who supports her. But there is still no land. So the animals volunteer to dive to the bottom of the deep waters to bring up mud.

The powerful animals – beaver, otter, others – try and fail. Finally, the small and seemingly weak muskrat dives, stays under for a long time, and comes back nearly dead, with a tiny bit of mud in its paws.

Sky Woman gently spreads this mud onto the turtle’s back. It begins to grow and grow, eventually becoming the continent itself.

This story does three things at once:

- It explains how land appeared.

- It gives a spiritual origin to North America (sometimes called “Turtle Island”).

- It teaches that even the smallest, humblest creature can achieve what the strong cannot, and that sacrifice can create an entire world.

5. Creation from Nothing (Ex Nihilo)

The final major pattern is creation out of nothing – known in Latin as creatio ex nihilo.

In these stories, there is no pre-existing chaos, no water, no giant parents, no previous worlds. There is only:

- a single, transcendent God, and

- a decision to create

This idea is central to the Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

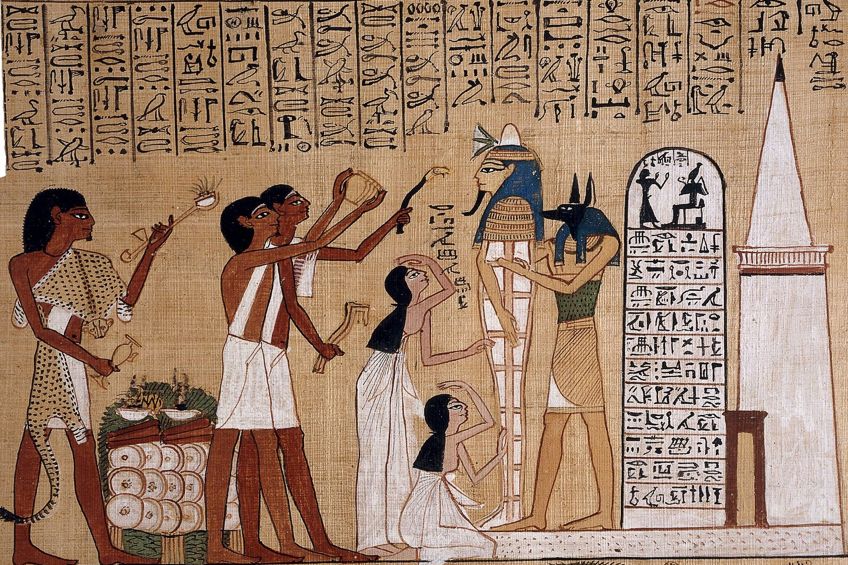

Genesis and the Power of the Word

In the Book of Genesis, the opening lines describe the earth as “formless and void,” with darkness over the deep. God does not shape pre-existing matter in the usual mythic way. Instead, he speaks:

“Let there be light”

And there is light.

Over six days, God:

- separates light from darkness

- shapes sky, sea, and land

- fills the world with plants, animals, and finally humans

By the 3rd century CE, theologians had developed this into a clear doctrine:

God created absolutely everything from nothing—not just reshaping matter, but bringing all reality into being.

This creates a sharp divide:

- God = eternal, uncreated

- The world = created, dependent

It’s not just a story of origin, but a statement about who God is and how different the divine is from the world.

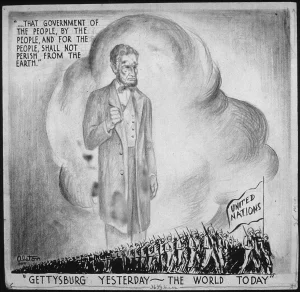

Why These Patterns Matter

When you compare these myths side by side, they come from different times and places, but they echo each other:

- Chaos myths show a deep human fear of disorder and a hope that someone—or something—can impose order.

- World Parent stories highlight separation, growth, and the pain of change.

- Underground and Earth-Diver myths stress journey, struggle, humility, and cooperation.

- Ex nihilo emphasizes the power, uniqueness, and freedom of a single creator.

Creation myths aren’t primitive science. They’re meaning-making tools. They don’t just tell us how the world began, but what kind of place it is, and what kind of people we are supposed to be.

Whether it’s a god slaying a dragon, a forest deity prying apart sky and earth, a muskrat bringing mud from the deep, or a single voice saying “Let there be light,” each story reflects what a culture values—and what it fears.

In listening to these ancient tales, we’re not just learning about the past. We’re also catching a glimpse of the questions that humans, everywhere and always, just can’t stop asking.