Svalbard is a scattered crown of Arctic islands, perched about 800 km (497 mi) north of mainland Norway and roughly halfway to the North Pole. To its west lies Greenland; to its east, Russia’s Franz Josef Land. The Old Norse name Svalbard means “Cold Coast,” while the Dutch once called the main island Spitsbergen—“jagged mountains”—for the sharp peaks that spear the horizon.

The archipelago totals 62,700 km² (24,208 sq mi) across nine principal islands. Spitsbergen is the largest at 37,673 km² (14,545 sq mi). Its administrative center, Longyearbyen, is widely known as the world’s northernmost permanently inhabited settlement, named after American entrepreneur John Munro Longyear, whose Arctic Coal Company began surveying and mining here in 1906.

From Terra Nullius to Norwegian Rule

For centuries Svalbard was a frigid commons—a terra nullius—where rivals hunted, mined, and explored without a single, recognized sovereign. That changed after World War I. On 9 February 1920, the Spitsbergen Treaty was signed in Paris; when it entered into force on 14 August 1925, Svalbard came under Norwegian administration and law. Even so, the treaty preserved non-discriminatory rights for other signatories to engage in commercial activities, a quirk that still shapes Svalbard’s international flavor.

Who Found Svalbard First?

History in the high Arctic is often written in ice and inference. Sparse sources and ambiguous notes have fueled four main theories about Svalbard’s “discovery.”

1) A Stone Age Presence?

In the 1970s, flint pieces turned up at Russekeila, a former Russian whaling site on Spitsbergen. Some archaeologists proposed Stone Age hunters might have reached the islands (perhaps following reindeer across drift ice). Later analysis in 1997 concluded the stones weren’t human-made tools. The hypothesis is largely rejected today, though a fleeting prehistoric presence remains conceivable given milder past climates and the Inuit’s deep Arctic knowledge.

2) The Norse in 1194

Medieval Icelandic sources—the Islandske Annaler—record “Svalbard” discovered in 1194. A line in the Landnámabók even reads like sailing directions: from Langanes (northeast Iceland), it is “four dœgr” to Svalbard “north of Hafsbotn.” The trouble? Dœgr can mean 12 or 24 hours, and “Svalbard” might refer to Jan Mayen, Greenland’s east coast, or western Spitsbergen. The Norse were exceptional navigators, so an early visit is plausible—but unproven.

3) Russian Pomors and “Grumant”

By the late 19th century, a Russian claim gained traction. A 1576 Danish royal letter (translated in 1901) suggested that Pomor seafarers from the White Sea region regularly sailed to Grumant—the Russian name for Spitsbergen. Pomors indisputably hunted across Svalbard from the early 18th to mid-19th centuries; archaeologists have identified multiple Pomor sites, with one possibly from 1545. Western skeptics note that early European whaling literature and maps don’t mark Pomor settlements before 1596. The verdict: substantial early presence, but discovery remains contested.

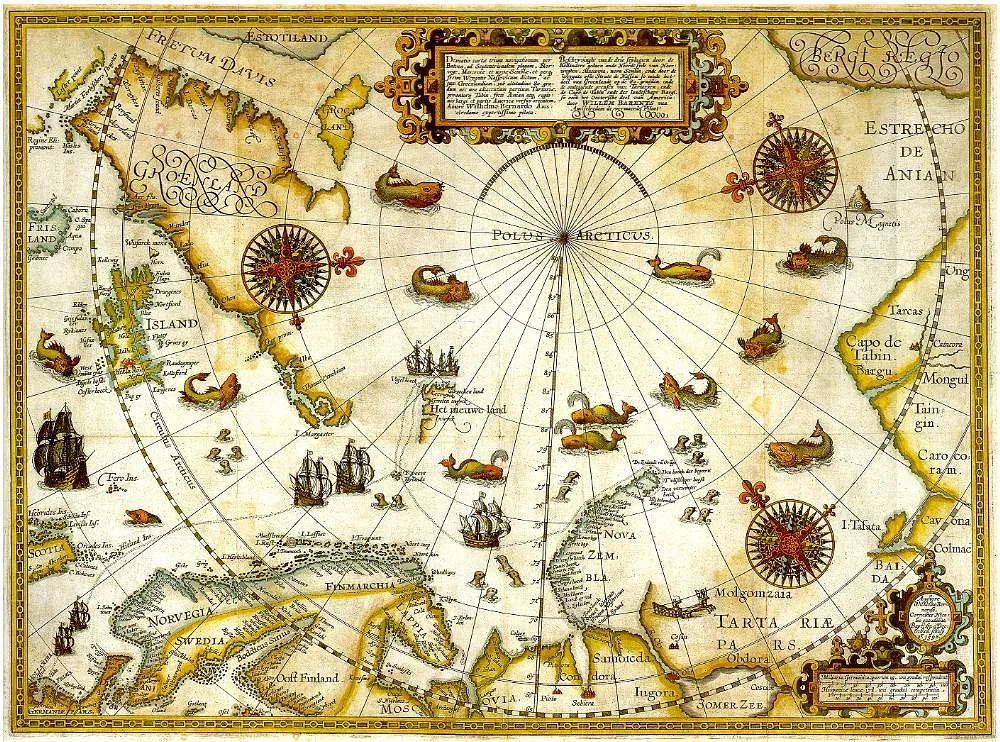

4) Barentsz and the Dutch, 1596

The standard Western narrative credits Willem Barentsz (c. 1550–1597), the Dutch navigator who, seeking a Northeast Passage to Asia, sighted Spitsbergen on 17 June 1596 after discovering Bear Island. This is the best-documented early encounter, making Barentsz the conventional “discoverer”—while leaving open the possibility of earlier, less recorded visits.

Barentsz’s Hard Winter—and the End of an Era

Barentsz made three Arctic voyages (1594–1596). On the final expedition, his ship De Witte Swaen (“The White Swan”) became locked in ice off Novaya Zemlya in August 1596. The crew dismantled timbers to build Het Behouden Huys (“the safe house”) and survived a brutal winter beset by scurvy and polar bears. Barentsz died on 20 June 1597 during the attempt to sail south in open boats.

The Dutch did not force a sovereignty claim. Guided by Hugo Grotius’s 1609 principle of Mare Liberum (the freedom of the seas), they treated Svalbard as open water for trade and hunting—an outlook that encouraged multinational activity in the decades that followed.

Oil of the 17th Century: The Whaling Boom

In the early 1600s, European demand for lamp and soap oil—and for baleen (whalebone) in corsets, umbrellas, and hoop skirts—sparked a rush to Arctic waters. The Dutch Noordsche Compagnie (founded 1614) and England’s Muscovy Company battled for advantage, hiring seasoned Basque harpooners and building shore stations to render blubber in vast copper kettles. The Dutch settlement of Smeerenburg (1619) became a bustling seasonal hub.

By the late 17th century, as many as 200–300 ships and over 10,000 whalers operated around Spitsbergen. The Dutch alone recorded 1,255 whales and 41,344 casks of blubber in certain tallies. Inevitably, stocks—especially Greenland right whales—declined. By around 1750, many coastal stations were abandoned and the hunt moved increasingly offshore.

Meanwhile, rival crowns postured. Denmark’s Christian IV argued Spitsbergen was part of Greenland; the English even referred to Spitsbergen as “Greenland” to bolster claims for James I in 1614. The Dutch largely ignored such assertions and carried on.

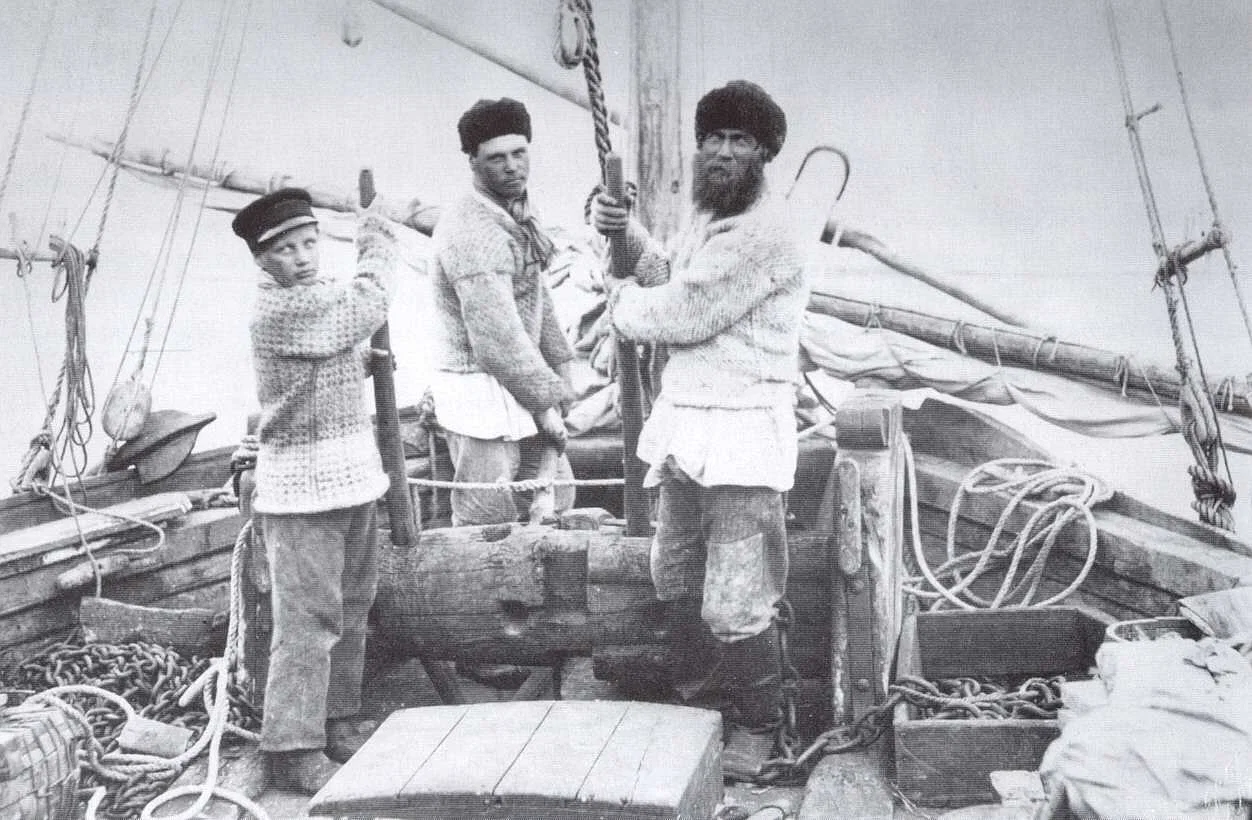

Trappers, Sealers, and the Pomor Winterers

As whalers pivoted to open-sea hunting, trappers and sealers reshaped Svalbard’s economy. Pomor crews—sailing lodyas from Mezen, Archangel, Kola, Kem, Onega, and Rala—built timber isbuschka (field huts) marked with Orthodox crosses and overwintered to hunt walruses, seals, foxes, reindeer, and polar bears. The winters were grueling; accounts describe men fighting lethargy through repetitive tasks just to keep mind and body from slipping in the long polar night.

The most famous Pomor resident, Ivan Starostin, spent 39 winters on Svalbard, dying in 1826 (Cape Starashchin bears his name). In the 1790s, some 2,200 Russian hunters in 270 vessels plied these waters. By the 1820s, diminishing walrus herds and poor returns thinned their ranks; the last recorded Pomor wintering season is 1851–1852.

Norwegian hunters increasingly took the lead. They were quicker to reach the grounds and pushed farther east. In 1861, the sealer-explorer Elling Carlsen circumnavigated the archipelago and identified Kong Karls Land. In 1898, Norwegians encountered Victoria Island, a new speck between Svalbard and Franz Josef Land.

Coal Towns and Company Flags

Coal was noticed early—English sealer Jonas Poole saw it at Kings Bay in 1610—but industrial mining only took off in the 20th century. In 1906, the Arctic Coal Company (Boston) under John Munro Longyear established Longyearbyen (originally “Long Year City”). By 1912, output reached 40,000 tons.

With no formal land rules between 1898 and 1920, more than 100 claims were staked. Swedes settled Svea; Russians developed Barentsburg and Pyramiden (today preserved as a Soviet-era ghost town); British players included the Scottish Spitsbergen Syndicate and the Northern Exploration Company. The population grew with mines, radio (1911), schools (1920), and even an early prefab hotel (1896).

Industrial risks were ever-present. In January 1920, an explosion in the American Mine 1 killed 26 miners. Over the decades, a string of closures followed on safety and environmental grounds. Norway’s state-owned Store Norske wound down operations and planned to close its last Svalbard mine in 2023—a symbolic bookend to the coal era that built modern Longyearbyen.

Svalbard Today

Modern Svalbard is a tightly regulated, strikingly international community where Arctic realities shape daily life. Among the quirks often cited:

- Firearms: Residents commonly carry rifles outside settlements for polar bear safety.

- Burials: The permafrost means no new burials in Longyearbyen.

- Cats: Prohibited to protect vulnerable birdlife.

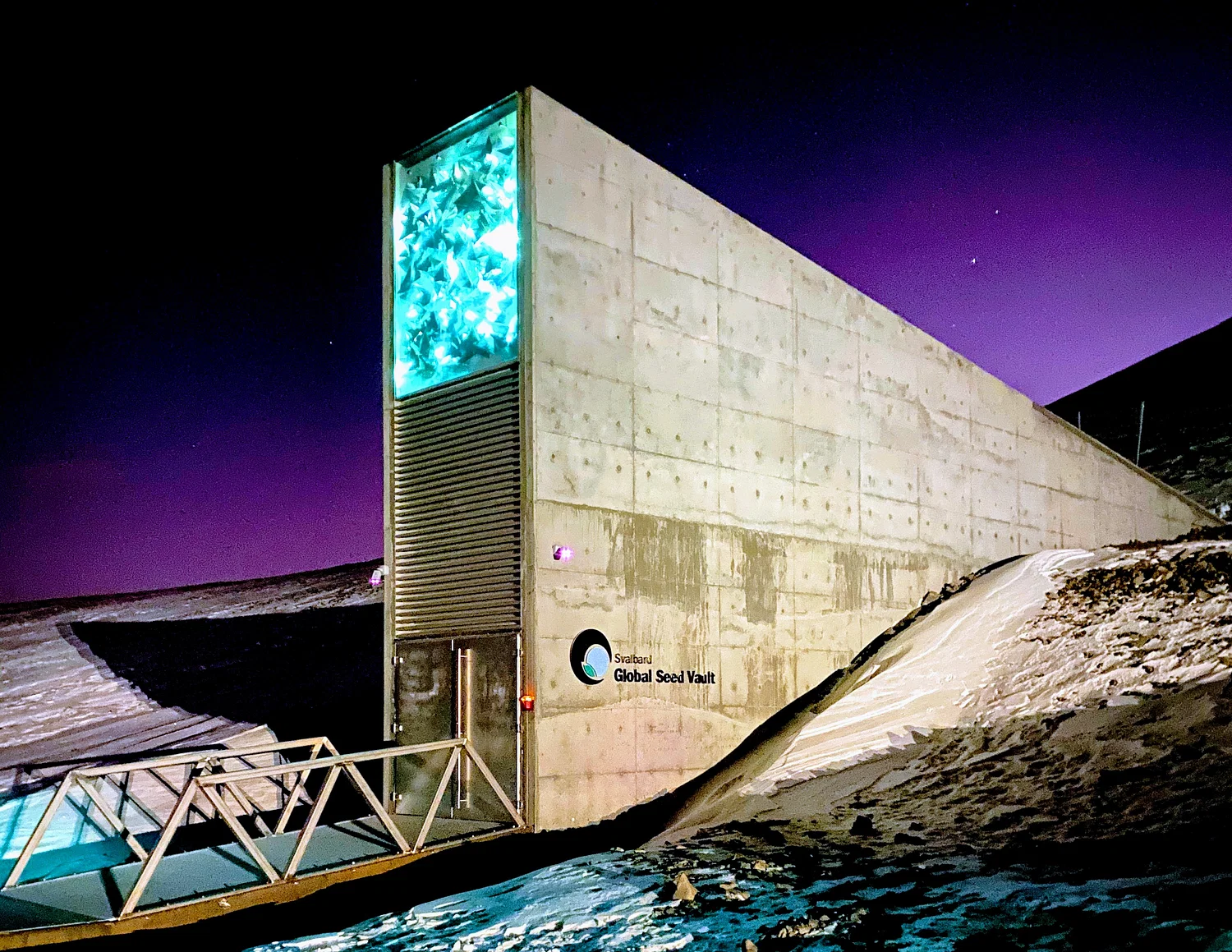

The most famous landmark of the 21st century is a bunker in the permafrost above the airport: the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Opened in 2008 inside a former mine, it safeguards millions of crop seed samples from around the world—insurance against war, disease, climate shocks, and simple human error. In a place once prized for whale oil and coal, the most valuable commodity now stored is genetic diversity.

A Short Timeline

- 1194 – Icelandic annals note a “Svalbard” (location debated).

- 1550s–1590s – Northern European attempts at Northeast Passage.

- 1596 – Willem Barentsz sights Spitsbergen; Bear Island discovered.

- 1610–1750 – Shore-based whaling booms then declines.

- 18th–19th c. – Pomor wintering, Norwegian hunting, new islands charted.

- 1906–1920 – Coal rush; Longyearbyen founded; over 100 land claims.

- 1920–1925 – Spitsbergen Treaty signed; Norwegian sovereignty begins.

- 1973 – Polar bears protected in Svalbard.

- 2008 – Global Seed Vault opens.

- 2023 – Store Norske plans closure of its last mine in the archipelago.

Why Svalbard’s Past Still Matters

Svalbard’s story is a microcosm of Arctic history: discovery myths and national pride, resource booms and busts, fragile ecosystems, and geopolitics navigated by treaty. It began as an unclaimed edge of the map and became a shared Arctic managed by law and science. Today, the archipelago’s most important export may be resilience—embodied in a vault built to outlast storms, wars, and generations.

If you’re planning a deeper dive into Svalbard—its wildlife, climate research stations, or hiking rules—consider pairing this history with a practical guide to staying safe and leaving no trace in the high Arctic.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

La Isabela: Colombus’s Fisrt Settlement

Swimming Through Time: The Secrets of Sahara’s Rock Art

Sylvia the Grizzly the Celebrity Bear in Yellowstone

Thrace – Birthplace of Ares and Spartacus

Sir. Lancelot: Arthurian Legend’s Greatest Knight

Ulysses S. Grant: Shy Farm Boy, Reluctant Soldier, Relentless Leader

Revolutionizing Medicine: The Discovery of the X-Ray

Locke and the Morality in Early Modern England

Players in the Guildhall

Julius Caesar and the Danger of Punishment Without Due Process

A Surprising, Long History of Veterinary Medicine

Aboriginal Tasmanians: Survival, Legacy, and Resilience