On an autumn day in 1765, Williamsburg’s main street boiled with anger.

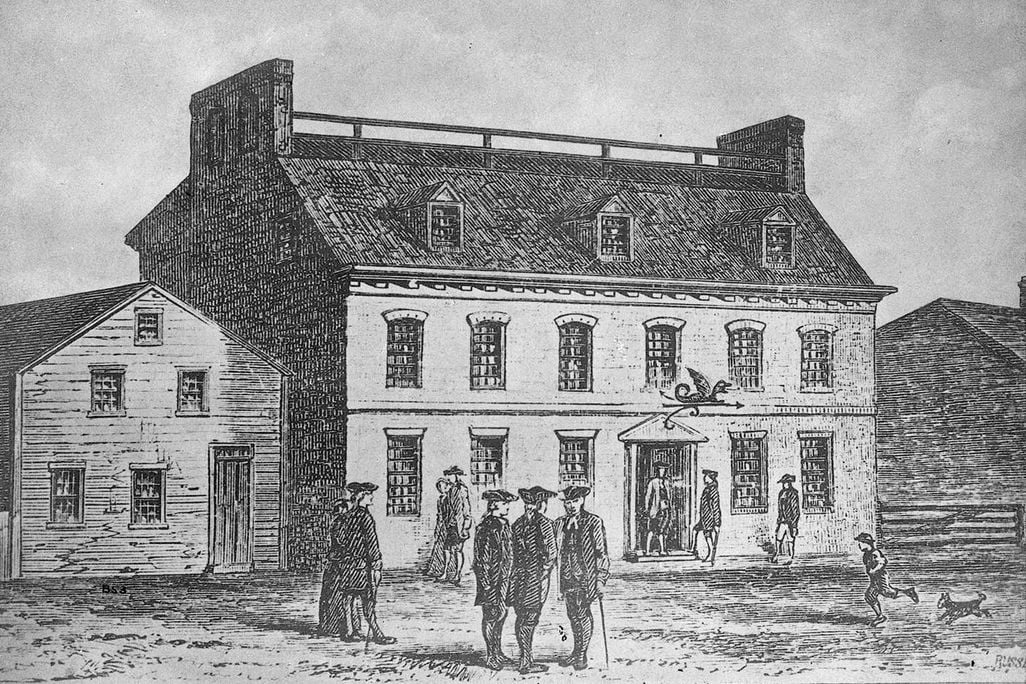

Virginia’s lieutenant governor, Francis Fauquier, was sitting on the porch of R. Charlton’s Coffeehouse, a fashionable spot on Duke of Gloucester Street where gentlemen, merchants, and officials came to sip hot drinks and trade news from across the Atlantic. As he looked up, he saw a furious crowd pushing its way toward him, voices rising, tempers flaring.

They weren’t after him—they were after George Mercer, Virginia’s newly appointed distributor of stamps under Britain’s brand-new Stamp Act. To colonists, this law was an outrage: a direct tax imposed by Parliament on everything from legal documents to newspapers, levied on people who had no voice in that Parliament at all. “Taxation without representation” wasn’t just a slogan; it felt like a direct insult to their rights as English subjects.

Mercer had arrived in town at exactly the wrong moment. Now, with an angry mob bearing down, he fled toward the nearest place that might offer some protection: R. Charlton’s Coffeehouse. Fauquier stepped in, calming the crowd and shielding Mercer from violence. Mercer got the message anyway. The next day, he resigned his post and returned to England.

The crisis passed, but the moment mattered. The Stamp Act controversy marked one of the first big flashpoints between Britain and her American colonies. And right there at the center of it stood a coffeehouse.

Coffee as Rebellion

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/bb/56bbf6fd-1004-48f0-8e50-4db593736816/coffeehouse2.jpg)

In colonial America, coffee wasn’t just a way to wake up in the morning. It was a statement.

Tea was tied to British identity, manners, and empire. By the 1770s, especially after the Boston Tea Party, many colonists began to see tea as a symbol of the very system they were resisting. Turning from tea to coffee became a quiet but powerful way to show where you stood.

This didn’t happen in a vacuum. The famous destruction of East India Company tea in Boston Harbor wasn’t actually about higher taxes making tea more expensive. The 1773 Tea Act lowered the price of tea in the colonies. The danger, as patriot leaders saw it, was more subtle: cheap taxed tea might tempt colonists into buying it, and by doing so, they would be accepting the principle that Parliament could tax them without their consent. That was the line they refused to cross.

Coffee, by contrast, wasn’t tied up with the same imperial symbolism. Drinking coffee instead of tea became both a patriotic gesture and a small act of defiance. But in truth, it wasn’t the drink itself that changed history—it was the places where people drank it.

What Made a Coffeehouse Different

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fb/fd/fbfd728f-c39c-4a9f-ba95-fa5f7db765e6/32d54b36-fef8-8b88-5de5401e0ba06a68.jpg)

Coffeehouses in the 18th century were not just cozy spots with good lighting and warm mugs. They were spaces where men from different backgrounds could sit together, talk openly, and soak up information.

The idea came from elsewhere. Coffeehouses first took root in the 16th-century Ottoman Empire and spread to Europe. In England, they flourished in the 1600s, earning the nickname “penny universities”: for the cost of a cup of coffee, you could listen in on discussions of politics, trade, science, and philosophy.

The first American coffeehouse opened in Boston in 1676, modeled on its English cousins. As historian Michelle Craig McDonald notes, colonial coffeehouses didn’t appear out of nowhere; they copied an existing model from across the ocean.

At first glance, they looked similar to taverns. Both were public meeting places. Both served drinks. Both offered a chance to relax and catch up on local gossip. But calling your establishment a coffeehouse instead of a tavern sent a signal.

Taverns were lively. People drank beer and spirits, ate, played cards, rolled dice, and sometimes stayed the night. Coffeehouses tended to be more sober—literally and figuratively. They attracted merchants, ship captains, lawyers, and other men of business who sat with newspapers and letters in hand, hashing out deals and arguing about politics. Coffeehouses often doubled as informal post offices and news hubs. Notices were pinned to walls or read aloud. Shipping lists, letters from London, and reports from other colonies circulated from table to table.

In a world where newspapers might appear only once or twice a week, and long-distance news traveled slowly, these spaces were crucial. Walk into Charlton’s in Williamsburg or a similar house in Annapolis and you might find the latest newspapers from Philadelphia, New York, Boston, or Charleston laid out on a central table. Knowledge really was power—and coffeehouses were how many people accessed it.

It made perfect sense that when colonists began to organize resistance—especially against laws like the Stamp Act—they chose to meet where they already worked, read, and talked: the coffeehouse.

Green Dragon, City Tavern, and the “Headquarters of the Revolution”

As tensions with Britain escalated, certain coffeehouses became legendary.

In Boston, the Green Dragon Tavern functioned as both tavern and coffeehouse, a hybrid that served beer and coffee alongside revolutionary gossip. The Sons of Liberty, the underground network of patriots formed in 1765 to oppose measures like the Stamp Act, were said to meet in its basement. Statesman Daniel Webster later called it the “Headquarters of the Revolution,” a nod to its role as a nerve center of plotting and planning.

In Philadelphia, City Tavern—also known as Merchants’ Coffeehouse—played a similar role. It served as an unofficial clubhouse for delegates of the First Continental Congress in 1774, including figures like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. It was at this coffeehouse that Paul Revere arrived from Boston with news of the Boston Port Act, the law that effectively tried to strangle Boston’s economy as punishment for the Tea Party. In an era before telegraphs or social media, coffeehouses were where such news landed and spread.

What made these places so powerful wasn’t just the presence of famous names. It was their accessibility. A coffeehouse allowed people from different social ranks to sit within earshot of one another, to trade rumors, argue, and ask questions. Even if formal congressional debates were conducted behind closed doors, the “chatter of the coffeehouse,” as John Adams once suggested, could be more open and revealing than anything said in an official chamber. In private, around small tables, people often spoke more freely, and ideas could be tested and sharpened.

From 1760s Rebels to 1960s Dropouts

The link between coffee and counterculture didn’t end with the American Revolution.

Two centuries later, in the 1960s, coffeehouses once again became the chosen habitat of people who wanted to challenge the status quo. Artists, writers, and musicians gathered in smoky rooms with guitars and notebooks in hand, reading poetry, playing folk songs, exhibiting paintings, and talking politics late into the night. They pushed against mainstream culture, questioning authority, war, and consumerism.

In a way, the pattern was familiar. Just as 18th-century coffeehouses provided an alternative to formal political spaces—places where you could test new ideas outside the gaze of the state—1960s coffeehouses made room for voices and forms of expression that didn’t fit neatly into traditional institutions. McDonald’s observation is spot on: what happened in the 1960s wasn’t all that different from what happened in the 1760s. Once again, coffeehouses served as informal laboratories of cultural and political change.

Coffeehouses as “Third Places” Today

Today, you can still sit down for a cup of coffee at R. Charlton’s Coffeehouse in Williamsburg. The building has been reconstructed on its 18th-century foundation, with much of its original wood framing incorporated, and reopened in 2009 as part of the Colonial Williamsburg experience. Visitors step through its doors not just for a drink, but for a taste of the environment where so many early arguments over British policy once unfolded.

Boston’s original Green Dragon is long gone, demolished in 1854, but a modern establishment bearing the same name opened nearby in 1993. Philadelphia’s City Tavern was rebuilt for America’s bicentennial in 1976; while it’s currently closed, the building still stands in Independence National Historical Park, a reminder of the days when coffee, news, and revolution mixed under its roof.

Of course, when people today think of American coffee culture, they’re more likely to picture Starbucks, Dunkin’, and other large chains. Yet alongside the big names, craft coffee has exploded, and independent coffeehouses are thriving in many cities and towns. Sociologists sometimes call these places “third spaces”—not home, not work, but a public, shared environment where people can relax, talk, and form connections.

That function hasn’t changed much since the 18th century. A coffeehouse that encourages reading, conversation, and lingering can still become a small engine of community life. It can host neighborhood meetings, political discussions, book clubs, open mics, and quiet one-on-one conversations that never show up in any official record but still shape how people see the world.

In recent years, the United States has even seen movements that revive the language of the Revolution, like a modern “Tea Party” protesting big government and taxes. If tea can be revived as a political symbol, why not coffee?

Perhaps it’s time to reclaim the older, radical side of coffee culture—to remember that some of the boldest experiments in American freedom were stirred into cups served at small tables, in busy rooms, where people traded letters, newspapers, and ideas. Coffeehouses helped nurture a revolution once. There’s no reason they can’t, at the very least, help us talk to each other more honestly now.