The story of King Alfred begins not in glory but in desperation.

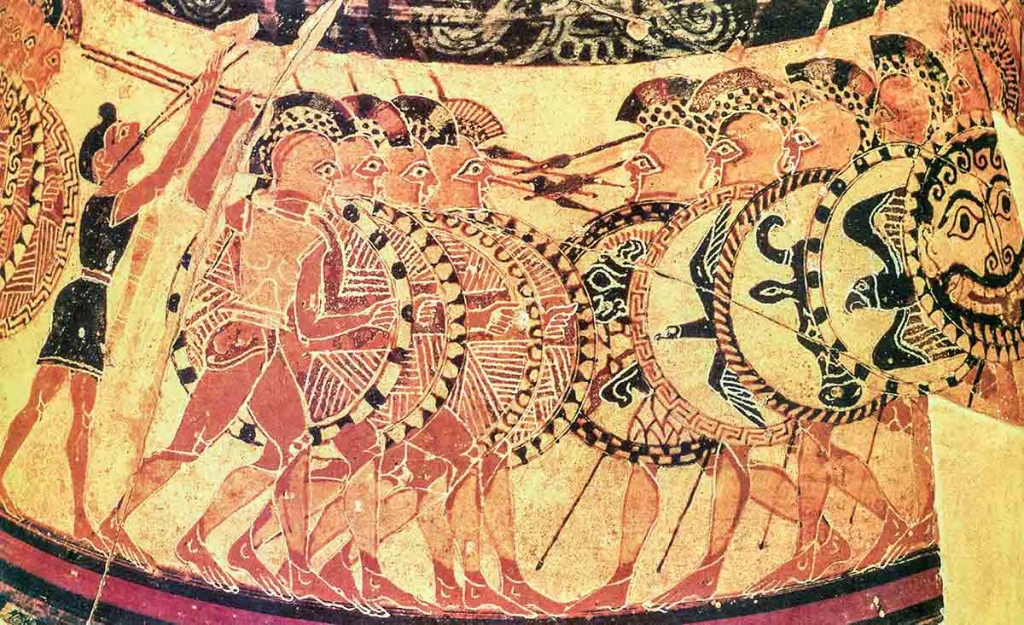

It was the year 871, and England teetered on the brink. The once-mighty Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were falling like dominos under the unrelenting blows of Viking raiders. The Great Heathen Army—led by fearsome Norse warlords—had already taken Northumbria, Mercia, and East Anglia. Only Wessex stood free, and even that was now cracking.

Alfred was the youngest of five brothers, never expected to rule. But fate has a habit of overturning expectations. One by one, his brothers died fighting the Danes, until the crown of Wessex—worn thin with worry and war—fell to Alfred. He was just 22.

From the start, his reign was a baptism by fire.

In the early days of his kingship, Alfred faced defeat after defeat. At the Battle of Wilton, he nearly lost his life and had to buy peace by paying the Danes tribute—what the English would come to call Danegeld. It was a bitter pill. The young king knew this was no true peace, just a pause in a long war.

But Alfred was not a man to surrender easily. He observed the Danes. He learned their tactics. He watched as they struck with terrifying speed, using rivers and coastlines to sail deep inland and vanish before a proper defense could be mustered. He realized that England’s survival would not come from brute force but from a total transformation of the kingdom.

Then came the darkest moment.

In 878, Alfred’s world collapsed. The Vikings launched a surprise winter assault, catching him off-guard. Wessex fell apart. His court scattered. His family fled. For a brief time, Alfred became a fugitive in his own land. He took refuge in the marshes of Somerset, cold, hungry, and uncertain.

This is where the legend begins.

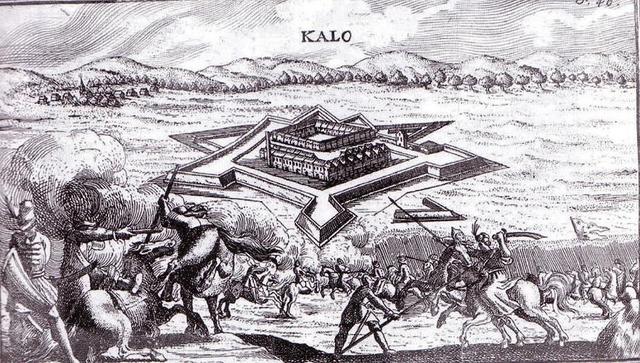

From a swampy stronghold in Athelney, Alfred plotted a comeback. He gathered loyal men. He forged new alliances. And he bided his time. It was during these months that a famous (though possibly apocryphal) tale was born: that Alfred, disguised and seeking shelter in a peasant woman’s home, was scolded for letting her cakes burn while he sat lost in thought. The story stuck, perhaps because it captured something vital—his humanity, his humility, and his focus.

In the spring, Alfred struck back.

At the Battle of Edington, he rallied his forces and faced Guthrum, one of the fiercest Viking warlords, in a decisive clash. Against the odds, Alfred won. He didn’t just drive the Danes from Wessex; he broke their confidence. He forced Guthrum to accept baptism and peace—real peace this time, sealed by a treaty dividing England between the Danelaw in the east and Alfred’s Wessex in the west.

It was a fragile victory, but Alfred did not squander it.

With the breathing room he had won, Alfred went to work—not just to defend Wessex, but to rebuild England.

He restructured the military. Instead of relying solely on the old fyrd (a kind of peasant militia), he created a system of rotating service. One half of the men worked the fields, while the other half stood ready to fight. He built a network of burhs—fortified towns—that allowed defenders to move quickly and resist raids. It was an early form of civil defense and local garrisoning.

He established a navy. The Vikings had ruled the seas, so Alfred constructed ships designed to outmatch them, longer and faster than those of the Norsemen. This was one of the first true English fleets.

But Alfred was not just a warrior king. He was a scholar, too.

He believed that ignorance had weakened England. The Danes may have been fearsome with axes, but Alfred feared something worse: the slow decay of learning. Latin, once common in monasteries, was vanishing. English clerks could barely read their own laws. To Alfred, this was unacceptable.

So he began translating key works into Old English—Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, Gregory’s Pastoral Care, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History—so that his people, even if they knew no Latin, could still access the wisdom of the past. He invited scholars from across Britain and Europe to his court. He saw kingship not just as a sword, but as a pen and pulpit.

More Stories

He even began a legal reform, gathering the various codes of old English kings—especially those of Ine and Offa—and unifying them into a more coherent system, infused with Christian ethics and a sense of justice. These laws were not just to punish but to guide, to educate.

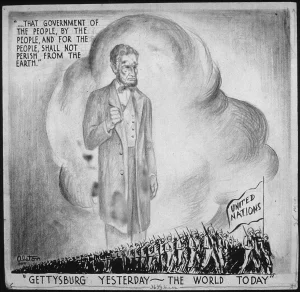

By the time of his death in 899, Alfred had done what no other English king had managed in over a century: he had held the line. More than that, he had given the idea of “England” a future.

His children and grandchildren carried the torch. His son Edward the Elder and daughter Æthelflæd (the Lady of the Mercians) would continue the war against the Danelaw. His grandson Athelstan would eventually become the first king to rule a unified England.

But it was Alfred who laid the groundwork.

He had turned defeat into defiance, exile into strength, and despair into hope. His reign was never easy—always at the edge of collapse—but it was during those perilous years that the English crown found its spine.

Centuries later, when the kings of England looked back for inspiration, they didn’t always look to Arthur or mythical heroes. They looked to Alfred. Not for legend, but for legacy.

The only English monarch ever to be called “the Great,” Alfred earned that title not by sheer power, but by perseverance, reform, and vision. In a world of burning monasteries and Viking blades, he built something stronger than a castle or a sword.

He built a kingdom of the mind.

And in doing so, he saved England.