The Day a Young Scholar Was Sold Like a Villa

Picture the clamour of a late–second-century BC Roman auction: traders haggling, senatorial aides taking notes, eyes drifting from fine furniture to finer human beings. Onto the block steps a young man, born in bondage yet polished by books. His name is Daphnis. He’s a verna—home-born slave—raised in the cultured household of the Accii, a family already famed for their literary connections. Someone reads out the price. Jaws slacken.

Seven hundred thousand sesterces.

It’s a sum that could buy a country estate or a showpiece townhouse. It’s almost double the wealth threshold for Rome’s equestrian order, the social tier just below the senate. And yet, rather than a mansion or plot of vineyards, Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, the leader of the senate, pays this stratospheric price for—what? For literacy. For the kind of education that allows a man to read, write, research, edit, recite, and add polish to the prose of Rome’s future.

Daphnis, Rome’s most expensive enslaved person of his time, wasn’t a labourer. He was, in effect, an elite knowledge worker. Scaurus later resold him to Quintus Lutatius Catulus, a powerful statesman and writer. Catulus soon manumitted him; as a freedman, Quintus Lutatius Daphnis may have composed a historical work—Shared History—that now survives only in fragments. Whatever Daphnis wrote, his sale, resale, and eventual freedom made a different sort of headline in Rome’s collective memory: books, brains, and training could be monetized on a breathtaking scale.

The saga of Daphnis is not just a vivid anecdote—it’s an entry point into a Roman habit that still surprises modern readers. Wealthy Romans didn’t only educate their sons. They educated their slaves, sometimes to dazzling heights, turning literacy into a domestic asset and a marketplace advantage.

Why Education Became a Household Investment

Rome’s obsession with letters had many sources: Greek influence, the explosion of political oratory, the status conferred by collecting libraries and patronizing poets. But behind those cultural ambitions lay a straightforward calculation. A literate slave did more.

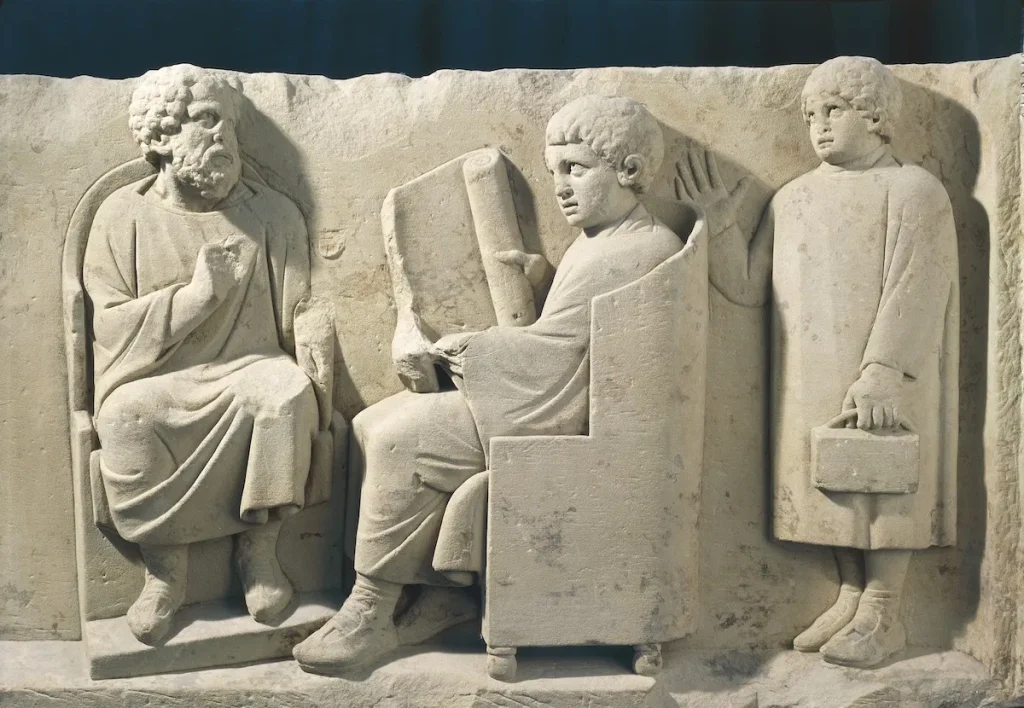

At the most basic level, a slave who could read, write, and keep accounts could track inventories, manage household budgets, draft receipts, copy letters, and support the business of life for a family with multiple estates. Yet Rome’s magnates didn’t stop at basic literacy. They trained some enslaved boys in the same advanced curriculum their sons followed—grammar, rhetoric, the handling of texts—because the return on investment could be spectacular.

These highly trained workers assembled and curated private libraries, copied and edited manuscripts, researched precedents and quotations for a patron’s speech, prepared drafts of treatises, and even coached friends and allies who lacked similar talent in their own homes. In a culture where fame blossomed from the written word—and where politics and prose were inseparable—an educated household wasn’t merely comfortable. It was strategically armed.

Cato’s Scheme: Turning Pedagogy into a Production Line

To see how deliberate this could become, step into the household of Cato the Censor (234–149 BC). Plutarch tells us Cato kept an enslaved teacher named Chilon. Cato taught his son himself—he liked to boast of plain virtues—but he set Chilon to teach the enslaved boys.

Cato pushed the model further. He encouraged members of his enslaved staff to invest their peculium—their personal savings accounts—in purchasing children (legally permitted in Rome, since a slave could own a vicarius, another slave). Cato then funded a year of training for these children in his own household. After a year, they were evaluated, and most were sold at a profit. Sometimes, Cato himself bought the best of them for the household.

On paper, it was shrewd. By dangling rapid returns, Cato enticed his workforce to put their savings into a project that served his interests. He harvested talent and profit simultaneously. The “school” became a pipeline: acquisition, instruction, sale. The literate slave wasn’t just a tool of administration; he was a product.

If that feels unsettling, it should. Roman education didn’t float on the pure love of learning. It rested on the auction block.

Atticus Builds a Fully Literate Home

Fast forward a century to Titus Pomponius Atticus (110–32 BC), Cicero’s wealthy friend—banker, investor, patron of writers—a man who preferred stability and culture to the knife-edge of republican politics. Atticus maintained a house on the Quirinal in Rome and large properties abroad. And he did something extraordinary.

Every male servant in his Roman household, says the biographer Cornelius Nepos, was both a reader and a writer—without exception. He filled his home with highly educated vernae (home-born slaves), trained to read aloud and to engage with literary work. Imagine a dinner party: a new history scroll arrives; a member of the household reads it with practiced cadence; another checks quotations; yet another prepares a polished copy for circulation. In Atticus’ home, learning wasn’t an ornament. It was the operating system.

The investment paid off in prestige and efficiency. Atticus hosted readings, curated conversations, and became a central node in Rome’s literary network from the 60s BC through the rise of Augustus. He even had a freedman secretary, Alexis, so skilled at imitating his hand that letters could pass for Atticus’ own—Cicero proudly claimed he could still tell the difference, a little boast of intimacy befitting best friends.

Atticus’ approach turned the household into a workshop of talent. One of his former slaves, Quintus Caecilius Epirota, later opened a school in Rome for advanced students and pioneered lectures on contemporary poetry—another marker that the homegrown syllabus of Atticus’ house found echoes in the city’s intellectual life.

Pliny’s Evenings: Walking with the Learned

The pattern persisted into the imperial era. By the time of Pliny the Younger (AD 61–113), wealthy homes had become ecosystems where education was both cultivated and casually assumed. Pliny’s letters—polished, public, and carefully curated—capture the texture of that world.

He mentions a dormitory of boys in his household and recounts, with a mix of credulity and curiosity, the tale of nighttime visitors who “sheared” the hair of sleeping youths—a story he frames as an omen of his own legal luck under the tyrant Domitian. The vignette is striking for how ordinary the setup seems to Pliny’s audience: rows of young boys, some advancing in literary studies, sharing a dorm in a grand house. A school within the villa, a cohort in training, a pipeline of talent that served the master’s reputation and routines.

In another letter, Pliny describes a summer day at his country estate that ends with dinner, a reading, music or comic performance, and then—his favourite part—an evening walk with members of his household whom he calls eruditi, “learned men.” The intimacy of the scene lingers: a master choosing to relax not with peers, not even with his wife after dinner, but with the minds he owns. The villa becomes both stage and seminar, where conversation polishes the day like a seal on warm wax.

The Literary Household as a Roman Institution

What emerges from Daphnis’ record price, from Cato’s pipeline, Atticus’ all-literate staff, and Pliny’s learned strolls, is a distinctively Roman institution: the literate household. It did not exist on this scale in most other slaveholding societies. Rome’s appetite for oratory, history, and poetry made literacy fashionable and useful; empire furnished a steady supply of enslaved people, some already educated, others chosen for their promise. Wealthy families poured time and money into training boys, especially vernae and sometimes children bought young, in hopes of creating the next indispensable librarian, editor, amanuensis, reader, researcher, or music instructor.

The benefits were immediate and visible. A private library cohered. A patron’s speech gleamed with apt citations. Friends could borrow a “house expert” to polish their prose. Books were copied, corrected, and launched into the world with the household’s invisible fingerprints all over them.

And this is where the modern myth of the solitary ancient author falters. Roman literature, even when signed by a famous name, often emerged from a team effort inside a single household: a circle of readers, emenders, note-takers, and stylists who made the scroll legible, persuasive, and elegant. The great voices of Rome had a chorus behind them—often enslaved or newly freed.

Prestige, Profit, and the Politics of Freedom

So how did education reshape the lives of the enslaved themselves? The answer is complicated.

For a few, like Daphnis, outstanding ability combined with good fortune to produce freedom—and a name. Manumission in Rome often came with strings: a debt of loyalty to the former master, now patronus. A freedman gained citizenship and legal rights, yet he remained bound in gratitude and obligation, his talents continuing to reflect glory on the house that had owned him. Catulus’ manumission of Daphnis was generous, yes—but also strategic. A famous freedman raises a patron’s prestige.

For the many, education meant expanded duty rather than liberation. Literacy multiplied the tasks one could be ordered to perform. A boy who proved clever might be kept indoors, spared the fields or the brute labour of construction. He’d spend late nights in lamplight, copying, collating, rehearsing, attending his master’s readings, and walking the villa paths to supply sparkle to an evening’s conversation.

It’s tempting to argue that literacy offered a path upward. Sometimes it did: better food, warmer rooms, a chance at manumission, perhaps a position as a trusted secretary. But it also bound a person more tightly to the owner’s ambitions, exposing intellect to the same logic as a plough or a press. Education raised the price on a body and deepened the household’s claim on a mind.

The Economics of a Curriculum

Training an enslaved boy to an advanced level took years—money for teachers, time for study, and a bet on the future. Not every child survived illness; not every mind flourished in rhetoric or meter. Households hedged their bets. They taught many; they kept the best; they sold others to recoup costs. Surviving records show that even seven-year-olds could be bought for education, with deeds noting their names and prices. Cato’s scheme reveals that a single year of training could increase a child’s market value enough to keep the machine turning.

Why did buyers line up? Because the household literatus was useful in every corner of elite life. He might liaise with book dealers, arrange scrolls by genre and author, maintain catalogues, and keep the papyrus rolls mended and legible. He could prepare a clean copy of a speech for a public reading, annotate the margins with historical exempla, or coach a young heir in declamation. He was the hinge between culture and daily administration, making a house run and a reputation glow.

Rome’s Reading Rooms: How Culture Became a Contact Sport

If we widen the lens, the literate household transforms how we imagine Roman culture. Think of the home library not as a static collection but as a buzzing workshop: wax tablets and papyrus slips, dictation and debate, scraps pinned into place, new texts tried aloud and revised after murmured critiques.

Atticus’ house became a salon where new works were aired before a discerning audience. Pliny’s villa functioned like a retreat: read, reflect, refine, and return to Rome with a polished text. Catulus’ patronage created the conditions for a freedman-author to write a history. Even Cato’s blunt pipeline of training and sale shaped the supply chain of talent that fed the city’s literary appetite.

When we read a speech of Cicero, a history of Sallust, or a poem recited in Augustan Rome, we hear the named author—but we are also overhearing a domestic chorus: the boy who found the right line in Ennius, the reader whose cadence convinced the master to cut a paragraph, the copyist who saved a delicate turn of phrase by catching a smudge before the ink dried. The “authorship” we inherit was, in practice, a team sport.

The Human Paradox at the Heart of Roman Learning

There is beauty in this world: the care lavished on books, the cultivation of voices, the earnest hunt for the right word. There is also cruelty: talent treated as an instrument, people as assets, intellect harnessed to reputations that profited from its brilliance while controlling its future.

Pliny’s evening walks with the learned are tender snapshots—warm twilight, conversation about poetry or history, a master content among minds he trusts. But there’s a shadow: those minds were bound to him by law and custom. Atticus’ elegant house, humming with recitations, hints at a republic of letters inside a single doorway—yet the citizens of that republic were owned. Cato’s “school” shows entrepreneurial genius—and the cold arithmetic of training children to sell them on.

To face this paradox honestly is to understand Roman culture more deeply. The empire fostered an ecosystem in which learning flourished inside captivity. The very texts that teach us about freedom, virtue, and the uses of history were sometimes produced, copied, or polished by people who had little control over their own lives.

Daphnis Again: What Is a Life Worth?

Return to the auction. Seven hundred thousand sesterces. The crowd murmurs as the bidding leaps like a heartbeat. Daphnis stands in the centre of a ring of men who have, in all likelihood, never copied a page themselves. They have orators to speak for them, librarians to fetch scrolls, readers to declaim, amanuenses to draft. They are in the market for a mind.

Scaurus wins. Years later Catulus frees Daphnis, and somewhere in between the young scholar edits, researches, perhaps writes his own book. His fragments whisper to us that he found a voice. Yet what lingers even more than fragments is the price—a number that tells us how Rome measured learning and how it turned pages into coin.

A clean conclusion would report that education set people free. The truth is uneven. Education raised some out of bondage. It also refined the tools of bondage itself. Rome’s literate households made the great conversation of the ancient city possible. They also reveal the cost at which conversation was often purchased.

What Rome Leaves Us

The Roman habit of educating enslaved boys to a high level is a distinct chapter in the global history of slavery and letters. It exposes how cultures convert ideals into systems: how the love of literature can coexist with the commodification of intelligence; how a household can become a seminary, a scriptorium, a stage—and a marketplace.

It also reframes our reading of antiquity. When we open a Roman text today, we hold in our hands the collaborative labour of many: patrons and authors, yes, but also teachers, readers, editors, accountants, musicians, and boys who grew up in dormitories where pranks—or prophecies—were acted out at night. We overhear the murmurs of evening walks, feel the press of wax tablets, smell the faint tang of lamp smoke over papyrus. We glimpse the lives behind the literature.

That double vision—admiring the craft, confronting the cost—is the gift and the burden of Daphnis’ story. It compels us to remember that knowledge has always been valuable, that education has always been a tool, and that the measure of a culture is not simply how highly it prices learning, but how humanely it treats the minds that make learning possible.

Key Takeaway

In ancient Rome, literacy was luxury—and leverage. Educated slaves formed the quiet engine of elite households, powering libraries, speeches, and books. Their work built reputations and shaped the literature we still read. Their stories remind us that the history of ideas is inseparable from the history of the people who produced them—often brilliantly, sometimes freely, and too often under the weight of ownership.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

History of Zulu People

Five US-Backed Counterrevolutions in Latin America

Ancient Medicine and the Four Humors

Story of the First Legend Hero: Cadmus

Axis Powers in World War II: The Rise and Fall of Tyranny

Catherine de Medici: The Italian Noblewoman Who Became France’s ‘Serpent Queen’

Four Great Cities of the Americas Before Columbus

Did King Arthur Really Invade Europe?

Peter (Simon) of the Twelve Disciples: The Rock of Faith and Redemption

The Clash of Titans: Rome vs. Antiochus the Great

Amenhotep III: The Sun King of Egypt’s Golden Age

The Tang Dynasty: Emperor Taizong’s Rise, Conquests, and Legacy