In the dusty aftermath of the War of 1812, the United States stood at a crossroad. Relations with Britain were warming, reducing the threat of foreign intervention on American soil. With the eastern seaboard secure and the promise of Manifest Destiny tugging hearts westward, the stage was set for one of the most transformative—and contentious—conflicts in North American history: the Mexican-American War.

Though it spanned less than two years, this war would redraw borders, ignite national debates, and leave a lasting imprint on both Mexican and American identity. Its sparks were struck long before the first shot rang out, and its consequences echoed decades into the future.

The Birth of a Powder Keg: Texas Joins the Union

The fuse was lit on March 1, 1845, when the United States annexed the Republic of Texas. Once a part of Mexico following its independence from Spain in 1821, Texas had been transformed by waves of American settlers who brought new culture—and new conflict. In 1835, tensions erupted in the Texas Revolution, a brief but brutal war for independence that saw iconic events like the Siege of Bexar, the Goliad Massacre, and the legendary stand at the Alamo.

Texas declared its independence on March 2, 1836, and by the Battle of San Jacinto, the war had turned decisively in favor of the Texan revolutionaries. Victory, however, was not a simple path to peace. As the Republic of Texas formed its fledgling government, many of its citizens pushed for U.S. statehood. The proposal ignited fierce debates—not only about expansion but also about the spread of slavery and the threat of Mexican retaliation.

Nevertheless, just days before leaving office, President John Tyler signed the annexation bill, and Texas was absorbed into the Union. The move stoked fury in Mexico, where leaders viewed the annexation as an act of aggression. With tensions simmering, it was only a matter of time before violence erupted.

Clash at the Border: The Thornton Affair

That flashpoint arrived on April 25, 1846. In the contested borderlands between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, a detachment of American troops under Captain Seth Thornton was ambushed by Mexican forces. Sixteen American soldiers were killed in the skirmish, an event that would be remembered as the Thornton Affair.

President James K. Polk, an ardent believer in expansion, seized the moment. Though he had previously attempted to buy California and New Mexico from Mexico for $30 million—a proposal flatly rejected—he now framed the conflict as a defensive war. With blood spilled on “American soil,” Congress had the political cover it needed. The United States officially declared war on Mexico in May 1846.

The First Battles: Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma

War came swiftly. On May 8, 1846, General Zachary Taylor led U.S. troops into the Battle of Palo Alto near present-day Brownsville, Texas. Using nimble artillery units, Taylor outmaneuvered his Mexican counterparts, driving them back with devastating precision.

The next day, Taylor struck again at Resaca de la Palma. This time, he captured key Mexican artillery positions and routed the opposition, securing the Rio Grande region for the United States. These twin victories gave the American war effort early momentum—and catapulted Taylor into the national spotlight. He would ride this popularity all the way to the presidency just a few years later.

Monterrey

With the northern front secured, Taylor pressed deeper into Mexico. His next objective: Monterrey, a fortified city critical to Mexico’s northern defenses. The siege began in September 1846 and quickly became a grinding, bloody affair. Mexican troops, under General Pedro de Ampudia, defended fiercely, using the city’s stone buildings and elevated terrain to their advantage.

After days of brutal street fighting, the Americans captured the strategic Bishop’s Palace overlooking the city. Recognizing the inevitability of defeat, Ampudia negotiated a truce. The United States would occupy Monterrey, but Mexican troops were allowed to withdraw with their arms intact—a decision that angered some American officers but preserved order in the occupied city.

The fall of Monterrey marked a turning point. The U.S. had not only proven its military strength but also gained a valuable staging ground for deeper incursions into Mexican territory.

March to the Capital

As winter turned to spring in 1847, General Winfield Scott launched what would become the most audacious operation of the war. On March 9, he orchestrated the first major amphibious landing in American military history, deploying 12,000 troops on the shores of Veracruz.

The city fell after a swift siege, and Scott began his march inland. His goal was nothing less than the heart of Mexico: its capital. The campaign was a logistical and strategic triumph. In battle after battle—from Cerro Gordo to Contreras—Scott’s troops advanced, often against superior numbers and harsh terrain.

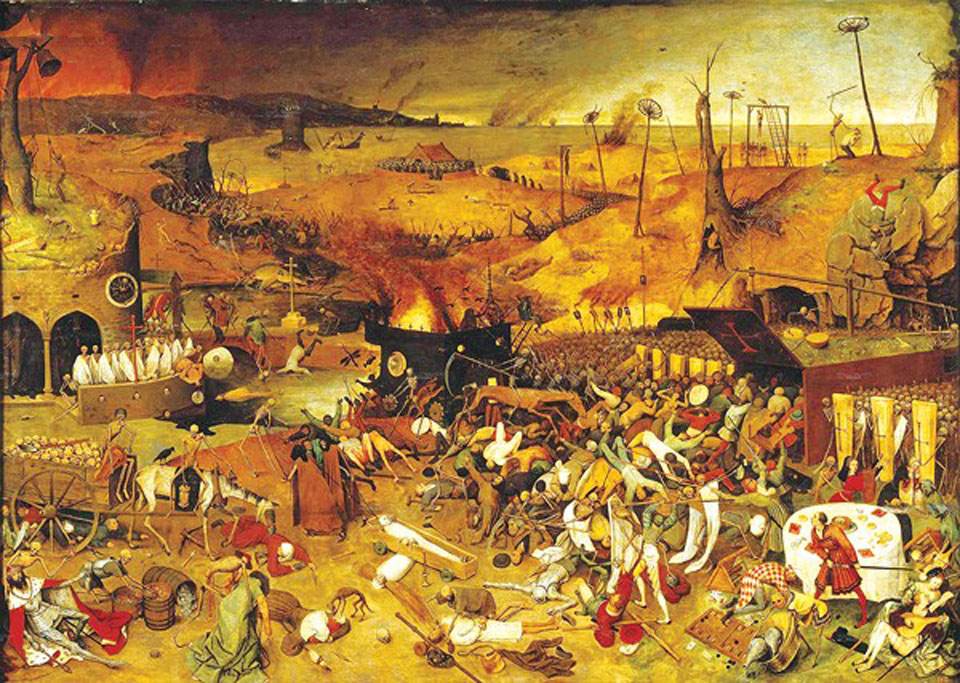

The climax came in mid-September at Chapultepec Castle, a hilltop fortress guarding Mexico City. On September 12, American artillery began a relentless bombardment. The next day, U.S. forces stormed the castle, overcoming valiant resistance from Mexican soldiers and military cadets—some of whom were mere teenagers.

By September 14, the Stars and Stripes flew over Mexico’s National Palace. The Mexican government had fled, and the war, for all practical purposes, was over.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Though fighting had ceased, negotiations dragged on. Finally, on February 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. The terms were staggering.

Mexico recognized the Rio Grande as the border of Texas and ceded a vast expanse of land—over 525,000 square miles. This Mexican Cession included what would become California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. In return, the U.S. paid Mexico $15 million and assumed $3.25 million in claims against the Mexican government by American citizens.

The deal was hailed as a triumph by expansionists. The dream of Manifest Destiny had been realized. The United States now stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Shadows of Victory

Yet not all were celebrating. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo left deep scars, particularly among those who lived in the newly acquired territories. Mexican residents were offered the choice to relocate south or become American citizens—a promise that was often honored in name only. Discrimination, land disputes, and cultural suppression followed.

Native American tribes also bore the brunt of expansion. The new territories accelerated westward migration, leading to the forced removal of indigenous communities. It was a continuation of a tragic pattern that had begun with the Trail of Tears.

Moreover, the war stoked the fires of sectional conflict in the United States. With so much new land, the question loomed: Would these territories permit slavery? The answer would divide the nation and pave the road to the American Civil War.