“Houses are built to live in, and not to look on,” Francis Bacon warned in the early 1600s. He was pushing back against a fashionable temptation: to treat architecture as a stage set rather than a working machine for life. That warning landed just as English elites were discovering architectural “theory”—translating Italian treatises, collecting pattern books—and as a new, fierce competition in building took hold. The result? In Elizabeth’s reign, the era of the “prodigy house”: vast, glittering, and each one a bespoke brag. But to understand how we got there, you have to start earlier—under the Tudors—where houses were as much instruments of royal policy as expressions of personal taste.

Before the Prodigies: Practical Books and Patchwork Courts

Early-Tudor courtiers lived in houses that often feel incoherent to modern eyes—accreted ranges, sprawling courts, and service yards stitched together over time. A lot of that fabric is gone (or “picturesqued” by 19th-century restorers), so we forget how workmanlike these places were. Builders leaned on handbooks of practice—where to site, how to drain, how to avoid “evil” winds—more than on Vitruvian decorum or Italian proportional games.

Even so, building was already part of a gentleman’s education and a badge of participation in politics. A great house signaled capacity and willingness to host the queen and her train—an expensive civic duty masquerading as glory.

The Crown’s Invisible Hand

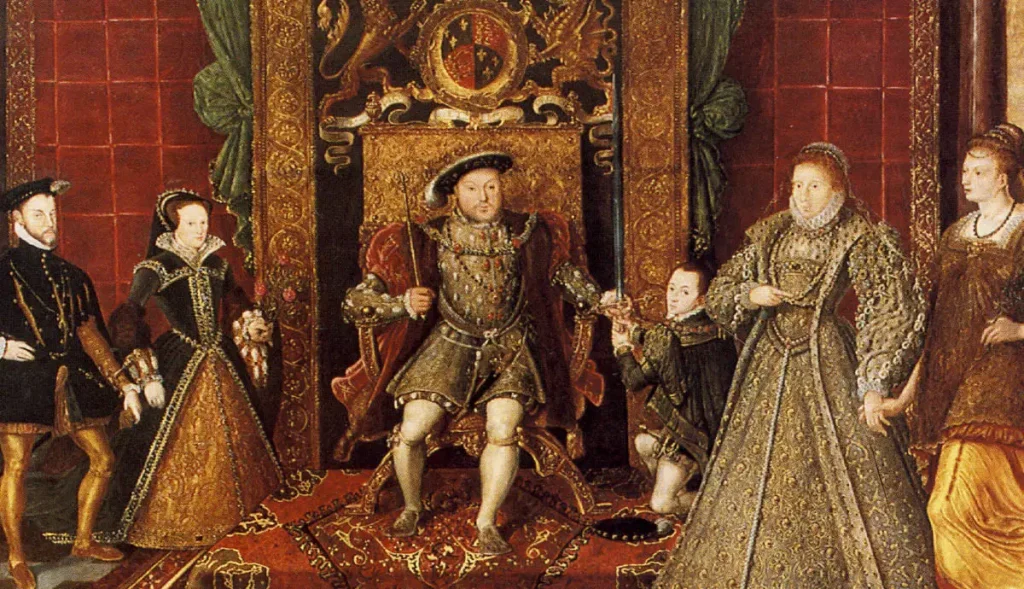

One reason early-Tudor houses look the way they do: the Crown actively moved pieces on the board. Attainders for treason, especially under Henry VIII, dumped whole estates back into royal hands. The king then recycled land—rewarding favorites, brokering swaps, or tightening control in “sensitive” counties. Add in the dissolution of the monasteries from the 1530s, and the king commanded a warehouse of properties to sell, gift, or leverage.

The arithmetic is stark: among roughly the top hundred men in Henry’s government and household, about two-thirds of their “new” houses (whether newly built or newly acquired) sat on land that had passed through the king’s hands.

Royal building also constrained private ambition. Holding offices like Constable, Steward, or Keeper of a royal castle wasn’t just ceremonial: it often meant living there—and investing there—rather than sinking money into a personal showpiece. Men such as Sir Francis Bryan (at Ampthill) and Sir Henry Guildford (at Leeds Castle) left little evidence of grand private projects; the Crown’s roofs served as their own.

Case Study: Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

If no Tudor career is “typical,” Charles Brandon—soldier, jouster, Henry VIII’s favorite—illustrates the mechanisms beautifully.

- Status through castles. Contrary to the tidy tale that castles simply yielded to comfortable “houses,” great lords still used castellated shells as status engines. Across England, medieval keeps were domesticated: defensive walks glazed into viewing galleries, curtain walls backed with brick halls and lodging ranges, chimneys corkscrewing above crenellations to advertise comfort inside. Donnington (Brandon’s Berkshire castle) likely sported heraldic glass in its hall—a flashing signal of pedigree and royal favor.

- A London stage: Suffolk Place. Brandon’s Southwark mansion—brick with terracotta dress, multiple courts—foreshadowed the grand Strand palaces to come. Around 1520, many courtiers still nested in City “lodgings,” expanding sideways as plots opened. Purpose-built town palaces, however, accelerated when Henry VIII forcibly “liberated” episcopal houses and handed them to favorites. Hence Fitzwilliam at Bath Inn, Russell at Carlisle Inn, Paget at Exeter Inn—and Seymour razing Chester Inn to raise Somerset House.

- East Anglia in brick, then a pivot to stone. In Brandon’s East Anglian orbit, he and Mary Tudor built at Westhorpe (terracotta figures were later recorded) and Henham (a brick courtyard house). They also occupied monastic lodgings—a common prelude to post-Dissolution ownership. After the Pilgrimage of Grace (1536), Henry redeployed Brandon as a power broker in Lincolnshire, engineering land swaps that shifted Brandon’s base north. There he rebuilt Grimsthorpe in stone, cannibalizing material from Vaudey Abbey—a literal conversion of monastic fabric into aristocratic presence.

- Budgets and debts. Courtiers could be stretched, but most didn’t spend more than about a year’s income on a single project. Brandon put his annual take around £2,500 in 1535 (likely conservative, and it swelled later). Some, like Surrey at Mount Surrey, overreached; others scored bargains in well-preserved former monasteries (Lacock, Newstead) for under £1,000.

How Royal Policy Shaped the Map

Tudor kings didn’t just reward loyalty; they deployed it. Want control in the West? Plant John Russell on former Tavistock lands. Want a steady hand in Lincolnshire? Move Brandon and his building power base there. The effect on architecture was immediate: materials, styling, and house types followed regional supply and new political tasks.

Meanwhile, as the Crown poured money into refurbishing and raising royal palaces, it set club standards but also absorbed talent, labor, and focus. Under Elizabeth, the equation flipped: as she sold off royal properties, magnates were driven to house themselves—and to compete—more intensely, helping to generate the spectacular prodigy houses (Hardwick, et al.) that are so hard to “tidy up” or disguise today.

Display, but With Prudence

If Wolsey’s fall taught anything, it was that display could backfire. Courtiers learned to talk small while building big. William Paget’s “poor cottage” at West Drayton had over fifty rooms and imported Flemish fireplaces by mid-century inventories. The line between gratitude and presumption was policed in stone, timber, and glass.

Which is why heraldry mattered so much. Shields in stained glass, carved oriels, painted ceilings, embroidered testers: a repeating armorial chorus that said we belong, we serve, we rise by the Crown. Often the royal arms sat above the family’s, a vertical diagram of power: favor at the top, family beneath. The surviving gate at Bromham (Wiltshire) distills the message—Baynton below, the king above—reminding us who could create (or unmake) such magnificence.

From Patchwork to Prodigy

Tudor houses were working instruments of rule: places to quarter retainers, feed hundreds, lodge the monarch, stage justice—and signal loyalty. They evolved from pragmatic compounds with opportunistic additions into deliberate machines of spectacle, especially once the court’s center of gravity shifted to great town palaces and then to the country-stage of the Elizabethan prodigy house.

Through it all, Bacon’s maxim shadows the story. The Tudors never forgot that a house must work—keep out wind, drain well, move servants unseen, feed armies of guests. But they also knew what Bacon half-fears: a house is always also a theatre. Under Henry VIII, the monarch wrote the casting and even picked the stage. Under Elizabeth, the players themselves began to design the scenery.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Five Timeless Types of Creation Myths Explained

Augustus: First Emperor of Rome

Ulrich Zwingli: The Swiss Reformer Who Shaped Protestantism

The Largest Urban Centers in Medieval Times

Axis Powers in World War II: The Rise and Fall of Tyranny

York: A Walk Through 1,000 Years of Medieval History

Women’s Voices in the French Revolution

How American Lend-Lease Trucks Fueled the Soviet War Machine in WWII

Royal Family Blood-Marriages in Ancient Egypt

A Postscript to Greek Ethics

Who are the Worst Traitors in History?

The Harpies: Winged Agents of Vengeance