Japanese Buddhist temples aren’t just religious buildings – they’re entire worlds. They give physical shape to Buddhist ideas, stand alongside Shinto shrines as a distinct spiritual tradition, and captivate visitors with sweeping roofs, bright colors, gilded ornaments, and serene gardens.

Nothing replaces seeing them in person, but this guide will walk you through how they work, what makes them different from Shinto shrines, and how their styles evolved across the centuries.

Shrines vs. Temples: Two Spiritual Architectures

Japan’s religious landscape rests on two pillars:

- Shinto – the indigenous, nature-centered belief system

- Buddhism – introduced from India via China and Korea in the 6th century

At first glance, it’s easy to confuse Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, but they differ in origin, feel, and architecture.

Shinto Shrines: Where the Kami Live

In Shinto, sacred power belongs to kami – divine spirits that can inhabit almost anything: mountains, rivers, trees, rocks, even ideas.

In ancient times, a “shrine” didn’t necessarily mean a building at all. Anywhere a kami dwelled and could hear prayers was a shrine: a forest glade, a waterfall, a mountaintop. When humans did build structures, they were often temporary – simple wooden frames set up in nature for a specific ritual, then dismantled afterward.

Over time, Shinto shrines became more permanent but never lost their connection to nature. Key traits include:

- Natural materials – unpainted wood, minimal metal, simple lines

- A strong preference for harmony with the landscape

- The tradition (still maintained at some sites, like Ise Grand Shrine) of rebuilding the shrine every 20 years using fresh materials

- The iconic torii gate, often painted vermilion, marking the boundary between the human world and the sacred space, and believed to ward off evil

Even when they’re elaborate, Shinto shrines feel light, open, and close to the natural world.

Buddhist Temples: Worlds of Enlightenment

Buddhist temples in Japan feel very different.

They are usually larger, more enclosed complexes, often surrounded by walls or fences, and guarded by fierce statues at the main gate. Their purpose is both inward and cosmic:

- To support individual practice and the quest for enlightenment

- To remind visitors of the Buddhist order of the universe

Typical features include:

- Tiled roofs with curving eaves, influenced by Chinese and Korean design

- Rooflines that, from a distance, resemble rows of ceramic pipes floating above white eaves

- Rich ornamentation – metal fittings, gilding, painted wood, carvings

- Numerous statues: Buddhas, bodhisattvas, guardians, animals

Where shrines often feel like sacred nature with a few structures in it, temples feel like self-contained cities of faith.

The Anatomy of a Buddhist Temple Complex

Japanese Buddhist temples are not usually just one building. They are compounds made up of several specialized structures, arranged according to tradition and sect.

One classic layout is the shichidō-garan, or “seven-hall complex.” Not every temple follows it exactly, but it’s a useful map of what you might find:

- Sanmon / Sammon – the main gate, often huge, with guardian statues inside

- Butsuden / Kondō – the main hall, housing the principal Buddha image and sacred relics

- Hattō – the lecture hall, where monks study and sermons are delivered

- Sōdō – the meditation and living hall for monks

- Yokudō – the ablution hall, used for washing and purification

- Kuri – the kitchen and administrative area

- Kawaya – latrines

Larger temples can also include:

- Jikidō – dining hall

- Shōrō – bell tower, where the great bell is struck to mark time and ceremonies

- Kyōzō – repository for sutras (Buddhist scriptures)

- Pagoda – a multi-story tower derived from the Indian stupa, via China and Korea

Pagodas are among the most recognizable structures: wooden towers with 3, 5, 9, or even 13 tiers, each level symbolizing layers of the cosmos. They often contain relics or ashes of devotees. Hōryū-ji, one of Japan’s oldest temples, is famous for its five-story pagoda.

Some temples became enormous. By the 11th century, Enryaku-ji on Mt. Hiei (near Kyoto) had over 3,000 buildings spread across the mountain. Today, about 150 remain, scattered over vast forested slopes.

Architectural Styles: How Temples Evolved

Over the centuries, Japanese Buddhist temples developed several distinct architectural styles. These styles reflect changing tastes, foreign influences, and different spiritual emphases.

Wayō: The “Japanese Style”

- Period: Heian (794–1185)

- Character: Simple, modest, nature-harmonious

Wayō (“Japanese style”) developed as Buddhism settled into the Japanese landscape and sought to blend in with native aesthetics. Its key traits:

- Thin columns and low ceilings

- Minimal decor and unpainted or lightly finished wood

- Flexible interiors with sliding screens, easily opened to merge indoors with outdoors

- A strong emphasis on gardens and natural surroundings

Thanks to Wayō, many temples became famous not only for their halls, but also for their carefully shaped, lush gardens.

Daibutsuyō: Monumental and Chinese-Inspired

- Period: Kamakura (1185–1333)

- Character: Grand, bold, imposing

Daibutsuyō (“Great Buddha style”) came from Song Dynasty Chinese influences and pushed in the opposite direction of Wayō’s restraint:

- Massive beams and bold structural elements

- Huge halls designed to host gigantic statues

- A strong sense of scale and power

The Great Buddha Hall (Daibutsuden) at Tōdai-ji in Nara, housing a towering bronze Buddha, is one of the best-known examples of Daibutsuyō.

Zenshuyō: Austerity for Zen Practice

- Period: Kamakura (alongside Daibutsuyō)

- Character: Minimal, quiet, meditative

Zenshuyō is closely associated with Zen Buddhism. It favors:

- Simple, subdued interiors and exteriors

- Earthen floors and dim spaces that encourage contemplation

- A focus on function over decoration

These temples feel calm and sparse, designed as tools for meditation rather than spectacles.

Setchūyō: A Harmonious Hybrid

- Period: Muromachi (1336–1573)

- Character: Blended, balanced, experimental

Setchūyō (“mixed style”) combines elements from Wayō, Daibutsuyō, and Zenshuyō into layered, often striking buildings. You might see:

- Simple, minimal upper structures set above bold, colorful lower floors

- Or the reverse: dramatic gilding and color on a structure surrounded by calm, natural scenery

A famous Setchūyō example is Kinkaku-ji (the Golden Pavilion) in Kyoto – a shining gold-covered upper structure, mirrored in a tranquil pond and framed by trees. It’s both extravagant and perfectly at home in its natural setting.

Tōdai-ji: The Temple of the Great Buddha

If there is one temple that captures the ambition of Japanese Buddhism, it is Tōdai-ji in Nara.

Founded in the 8th century by Emperor Shōmu, Tōdai-ji was built to promote Buddhist unity and protection for the entire nation. At its heart stands the Daibutsuden, the Great Buddha Hall, which houses a colossal bronze statue of Vairocana Buddha.

The hall has burned down multiple times (notably in 1180 and 1567), and the current structure dates to the Edo period (1603–1868). Even so, it remains:

- Over 57 meters wide

- About 48 meters high

- One of the largest wooden buildings in the world

Walking into the hall, you feel two things at once:

- The earthly presence of massive timber columns and natural materials

- The otherworldly stillness of the Buddha statue staring out from the gloom

Together, they express the core of Buddhist temple architecture: grounding in this world, oriented toward another.

Nearby stands the Shōsō-in, Tōdai-ji’s treasure house. Built with:

- Raised floors

- Stacked timber walls

- Solid stone foundations

it’s a masterpiece of functional design. Its construction protects precious artifacts from humidity and pests, preserving relics of Japan’s early Buddhist history.

Warrior Temples and Fortified Faith

Japan has a long tradition of warrior monks (sōhei), going back to around the 10th century. Monasteries like Enryaku-ji wielded both spiritual and military power.

Yet, despite the presence of martial monks, the basic temple architecture stayed surprisingly consistent. Big temples could improve their defenses by:

- Digging moats and ditches

- Building embankments and palisades

- Taking advantage of steep mountainsides

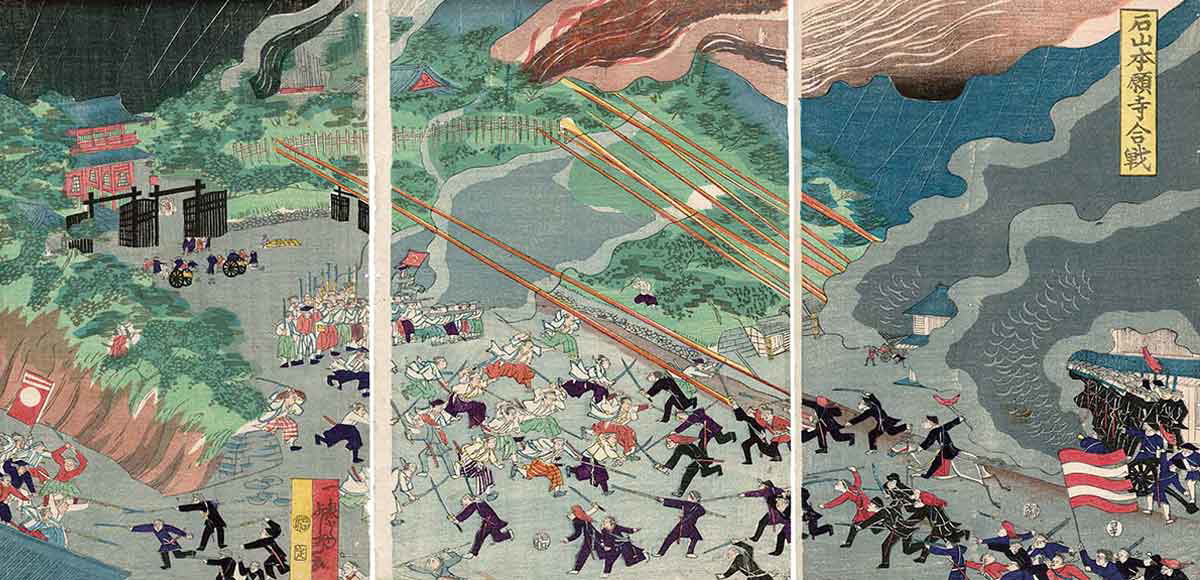

But true fortified temple complexes came with the Ikko-Ikki – leagues of militant Buddhist peasants and monks, especially powerful in the 15th–16th centuries.

Temples like Ishiyama Hongan-ji looked much like castles:

- Sacred areas with heavily fortified gates, terraces, fences, moats, and ditches, protecting the main hall, lecture hall, and sutra storehouses

- Secular areas, also walled but less heavily defended, housing living quarters, kitchens, and refectories

These sites were essentially two cities in one: a fortress and a monastery. By the height of the Sengoku (“Warring States”) period, it could be hard to tell a warlord’s castle town from a major fortified Ikko temple complex.

Why Japanese Buddhist Temples Fascinate

From simple Wayō halls hidden among cedar trees to golden pavilions shining over quiet ponds, from austere Zen compounds to colossal halls built for giant Buddhas, Japanese Buddhist temples are endlessly varied. Yet they all circle around the same themes:

- A bridge between nature and the sacred

- Spaces carefully shaped to guide the mind toward stillness or awe

- Architecture as a living expression of belief, politics, history, and art

If you ever visit Japan, temples are not just tourist stops. They are lessons in how a culture tried, again and again, to build places worthy of both the world we live in and the enlightenment it hopes to reach.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

King Octa of Kent and the Clockwork of Arthur’s Age

How Did Czechoslovakia Become a Country?

Heracles and the Cretan Bull: The Seventh Labor

Manichaeism: The Forgotten Religion That Rivaled Early Christianity

Diocletian and Constantine: On the Threshold of the Fourth Century

Livia Augusta—First Roman Empress

Svalbard: From “Cold Coast” to Doomsday Vault

The Seljuks: From Nomads to Sultans

Saint Patrick: The Life and Legends of Ireland’s Patron Saint

Scandal, Sorcery, and Secrets in Louis XIV’s Court

The Assassination of Caesar: Why the Ides of March Mattered

The Fourth-Century Church: Doctrine, Organization, and the Patristic Legacy