In the summer of 1845, a clammy fog settled over Ireland. Rains came more often than they should. When farmers dug into their potato ridges, the tubers slid apart in their hands—brown, soft, ruined. The air reeked of rot. What began as a strange blight on a single harvest spiraled into the Great Hunger, a disaster that reshaped Ireland’s people, economy, and history.

Why Potatoes Mattered So Much

Centuries of English conquest and land policies had pushed many Irish families onto poorer, western soils. Large estates—often owned by absentee landlords—were leased to tenants who grew “money crops” like wheat, oats, and barley to pay rent. That left the potato to feed the family. It thrived in thin soils, needed little land, and a single acre could sustain a household for a year. By the 1840s, roughly two-thirds of small farmers relied almost entirely on potatoes for daily subsistence.

The culprit, Phytophthora infestans—an oomycete often called late blight—spreads fastest in warm, wet weather. It blackens leaves, fuzzes the undersides with white growth, and turns the tubers themselves brown and mushy. Some potatoes looked sound at harvest only to rot in storage. The disease, recorded in the United States by 1843, moved through Europe and was noted in Dublin’s Botanic Gardens in August 1845. One failed harvest would have hurt; repeated failures turned hardship into calamity. Because potatoes were planted from saved tubers, each ruined year also meant fewer seed potatoes for the next.

It Wasn’t Just a Plant Disease

Blight lit the match, but policy and structure fed the fire. A monoculture of a single variety—the “Lumper”—left fields uniformly vulnerable. Rents and export-driven agriculture locked tenants into paying landlords first and feeding families second. Relief from Britain and other authorities proved halting and inadequate, while relentless rains kept spreading the pathogen. The result was not merely a bad harvest but a systemic failure.

Even at the height of hunger, up to three-quarters of Ireland’s arable land still produced export crops—wheat, oats, barley—largely shipped to England, sometimes under military guard. These grains could have fed thousands at home. Their steady departure deepened both the famine itself and the bitterness that followed.

“Famine Fever” Made Everything Worse

Starvation weakens the immune system. Disease did the rest. Cholera, typhoid, dysentery, scurvy, and typhus tore through crowded cabins, workhouses, and roadside encampments. Lice spread easily where hygiene collapsed. As families abandoned their plots to seek work or food, infections raced ahead. Roughly half of famine deaths are attributed to disease rather than starvation alone.

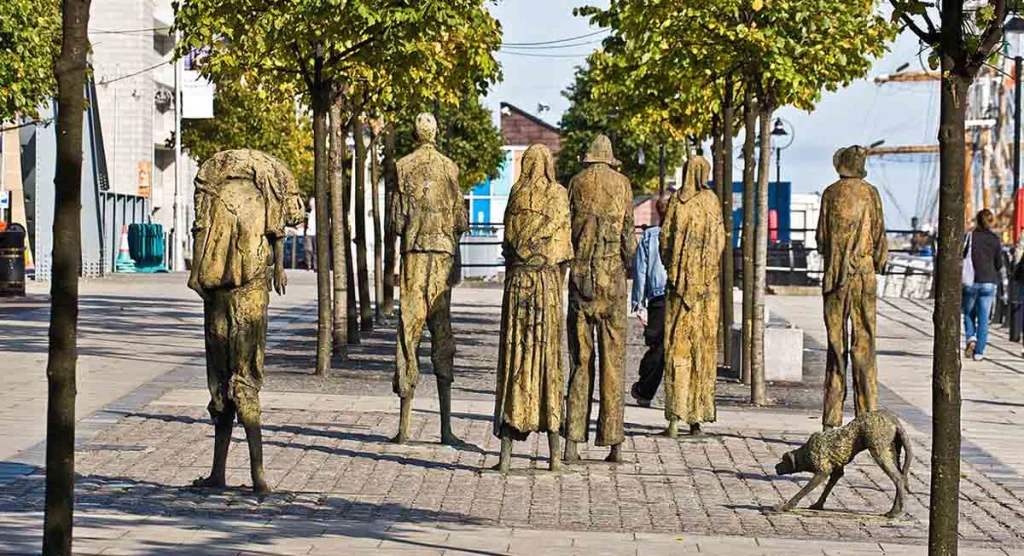

No one can count the dead exactly, but about one million people—roughly 12% of Ireland’s population—likely perished. Millions more left their homes. Between 1845 and 1855, vast numbers emigrated: around two million to the United States and Australia, and hundreds of thousands to Britain. Many sailed on overcrowded “coffin ships,” where mortality could run from 5% to 30% thanks to disease and squalid conditions. The exodus became the largest single population movement of the 19th century and would shape the politics, labor movements, railroads, and cityscapes of the United States. Today, an estimated 15% of Americans claim Irish ancestry.

Early Global Relief Efforts

While official British responses often fell short, compassion arrived from unexpected places, marking one of the earliest international relief efforts to a natural disaster. Funds and supplies came from cities in India, from Quaker networks in the United States, and famously from the Choctaw Nation—who had themselves endured the Trail of Tears—whose donation forged a lasting bond with the Irish town of Midleton, later honored with a commemorative sculpture.

Before the blight, Ireland’s population had topped eight million and was still rising. By 1851 it had fallen to about six million—and continued to decline for a century due to ongoing emigration and instability. Only in 2022 did the population again surpass five million. Even now, it has not returned to pre-famine levels.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Egyptian Art: From Balance to Brilliance

Plato’s Gorgias: Rhetoric, Morality, and the Pursuit of the Good Life

Jan Smuts: South African Leader, Global Statesman

Crassus and the Catastrophe at Carrhae

Medieval Ethiopia: Birth of the Solomonic Dynasty

The Largest Urban Centers in Medieval Times

5 Arctic Explorers Who Revealed the Unknown World

The Clash of Titans: Rome vs. Antiochus the Great

Roman Senate: Backbone —and Burden—of a World-Conquering Republic

Sintra: A Fairy-Tale Town Steeped in History

A Historical Jesus: True or Untrue

The Tang Dynasty: Emperor Taizong’s Rise, Conquests, and Legacy