Early medieval Britain is a landscape of half-lit corridors—names that flicker, dates that shift, and chronicles that argue with each other across centuries. Among these ghosts stands King Octa of Kent, an Anglo-Saxon ruler whose outline appears just long enough to raise more questions than answers. He is not the most famous of Kent’s early kings—far from it—but he matters, because the timing of his reign touches a much larger mystery: when, if ever, did King Arthur live and fight?

The puzzle looks straightforward at first glance. Octa is said to have ruled the Kingdom of Kent in the southeast, one of the earliest Anglo-Saxon polities to take root after the migrations to Britain. Some writers make him the immediate heir to Hengist, the much-lionized leader who brought Saxon mercenaries (and then settlers) across the sea. Others make Octa the next generation—Hengist’s grandson, not his son—placing him later on the royal bench. That gap is not an academic quibble. Move Octa forward or backward by a generation and you tug the thread that many historians use to pin down the supposed days of Arthur, because one of the earliest Arthurian source passages turns the page from Octa’s ascent to Arthur’s wars.

So we face two intertwined riddles: Who exactly was Octa—son or grandson? And if we settle that question with any confidence, what does that do to the dates often proposed for Arthur’s rise and the battles that follow?

Two Competing Lineages

The king lists of early Anglo-Saxon England are patchworks—part genealogy, part memory, part politics. When Octa steps onto the stage, two versions of his parentage take turns under the spotlight.

One tradition makes Octa the son of Hengist and his successor in Kent. In this telling, the torch passes directly from the founding war leader to his boy, as neat and linear as a genealogical roll in a monastery scriptorium. The other tradition claims Octa was the son of Oisc (also rendered Oeric), who was himself the son of Hengist. That would place Octa a generation later and rearrange the order of early Kentish rulers: Hengist → Oisc → Octa. The difference is roughly the span of a lifetime—twenty to thirty years in early medieval terms, sometimes more.

Why does the disagreement exist? Because the sources that mention Octa do so with different aims and at different distances from his day. Some are writing English church history from Northumbria; others are compiling British origin stories during a time of pressure from Germanic kingdoms; still others are capturing annal entries that evolved over time. Each text drags its own context along like a cloak—and with it, its own biases, gaps, and simplifications.

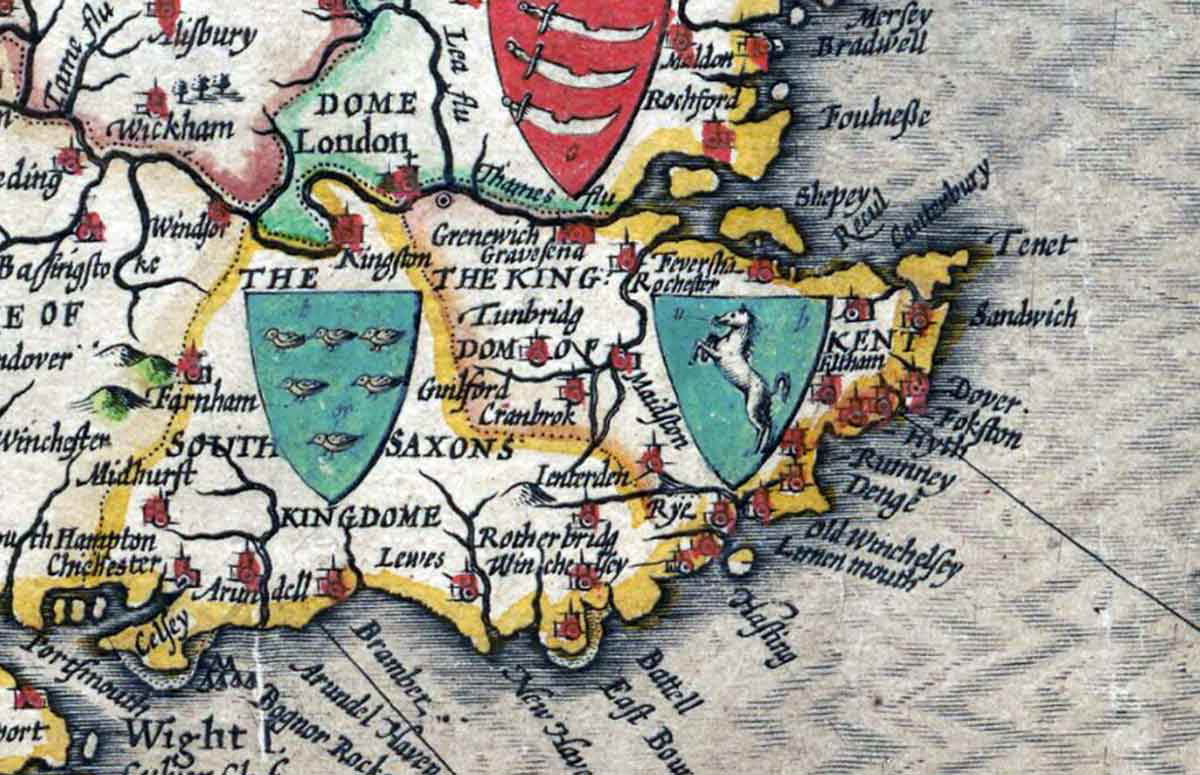

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a late ninth-century compilation that stitches together earlier material, does not even mention Octa by name when it talks about Kent’s earliest rulers. Instead, it highlights Oisc as Hengist’s son and gives Oisc a reign beginning in 488 and lasting twenty-four years. That solitary detail becomes a lodestar when we try to place Octa, because it nails down a rough window for Oisc’s authority—ending around 512—against which Octa must be plotted.

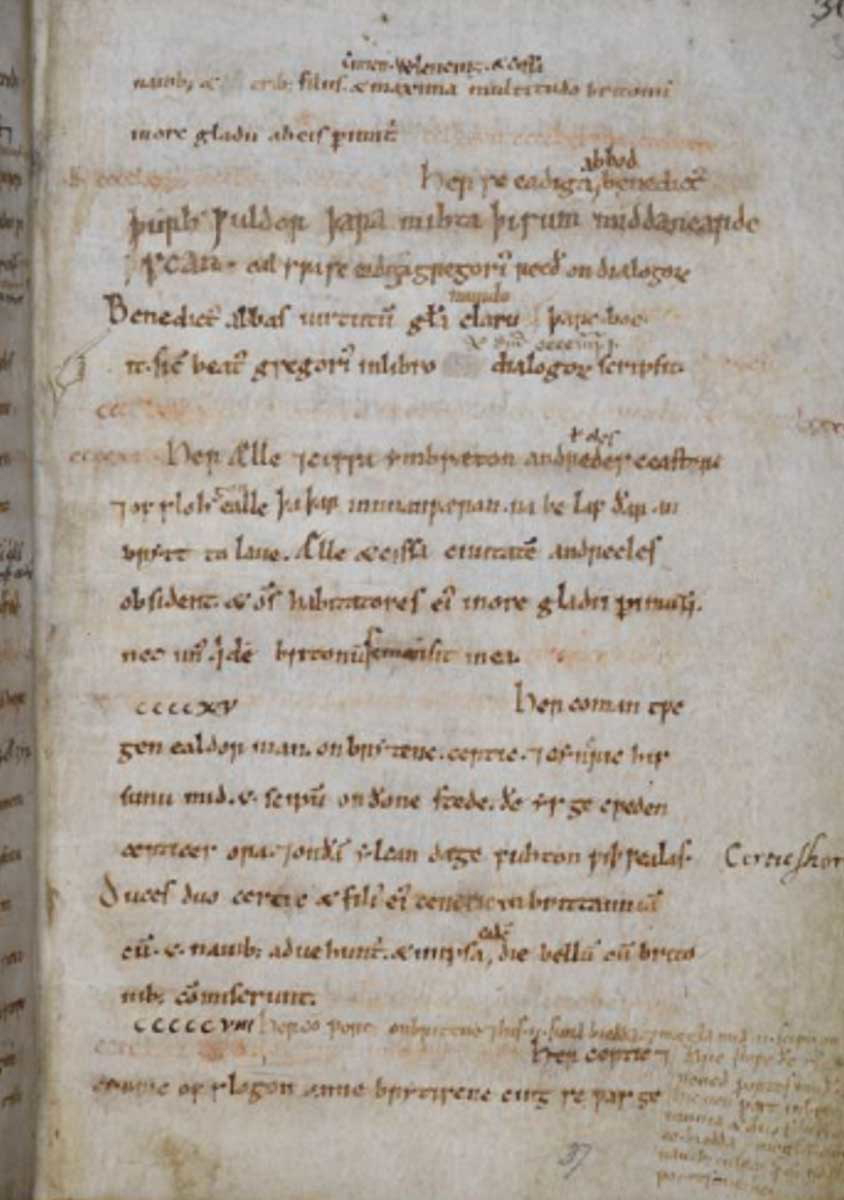

Meanwhile, the Historia Brittonum, traditionally dated to around 830, calls Octa the son of Hengist and presents him as the next Kentish king. On paper, that seems to swing the argument back to the “son and successor” camp. But the Historia also slips in a crucial remark: Octa’s reign belongs to the time after the death of Saint Patrick, which most reckonings place in the 490s. If Oisc’s reign begins in 488 and Octa’s belongs to the years after Patrick’s passing, then we’re more naturally looking at Octa as Oisc’s successor—not Hengist’s—even in the very source that names him as Hengist’s son. The text’s own chronological hints undercut its genealogy.

When sources talk out of both sides of their vellum, we need an earlier voice.

Octa’s Shadow on Arthur’s Shield

Why does this genealogical housekeeping matter beyond Kent? Because one of the earliest surviving sketches of Arthur’s career hinges on the moment Octa takes Kent. The Historia Brittonum lists twelve battles fought under Arthur’s leadership—the famous tally that ends with Mount Badon—and places the opening of those conflicts “in those days” when Octa came “down from the north of Britain to the kingdom of the Cantii” (Kent). The phrasing isn’t a legal timestamp, but the sequence is clear enough: Octa takes Kent; then Arthur fights “together with the kings of the Britons,” serving as their dux bellorum, their war leader.

If Octa’s accession falls later rather than earlier—if he is Oisc’s son and takes the throne after roughly 512—then the period in which Arthur is imagined to have led those campaigns shifts forward too. That complicates efforts to reconcile the legendary list of Arthurian battles with archaeology, late Roman military decay, and the dating of fortifications and burials in lowland Britain. Slide Octa back a generation by making him Hengist’s son and successor, and Arthur’s wars can be plotted earlier, closer to the mid- to late- fifth century; push Octa forward, and Arthur inches toward the sixth.

There is an irony here that would make a monk smile: the era’s most famous perhaps-king, Arthur, depends for his chronology on a definitely lesser-known king, Octa. Two shadows, one clock.

Listening to the Earliest Witnesses

When texts disagree, historians often reach for the earliest and most sober voice. In this case, that is Bede, the eighth-century Northumbrian monk whose Ecclesiastical History of the English People (completed around 731) is a cornerstone for early English history. Bede is careful with his material, occasionally infuriatingly cautious, but reliable where he can be. He presents Octa explicitly as the son of Oisc, who is himself the son of Hengist. That lineage—Hengist → Oisc → Octa—places Octa in the next generation, not the first.

Bede has another advantage besides age. He writes with a clear eye to chronology, cross-checking regnal lists against church events and missionary careers. That habit helps to tether the Kentish names to broader timelines. If we trust Bede’s order, then the Chronicle’s notice that Oisc ruled from 488 for twenty-four years fits nicely: Oisc’s death around 512 would naturally open Kent for Octa’s accession.

Now fold back in the Historia Brittonum’s clue about Saint Patrick’s death—often placed in the 490s—and the picture sharpens. Octa is active after Patrick dies; Oisc’s reign starts in 488; Bede makes Octa Oisc’s son. All the pieces point in the same direction: Octa belongs to the early sixth century as Oisc’s successor, not to the late fifth as Hengist’s immediate heir.

There is one more chronological thread sometimes overlooked in popular retellings: the date of the Saxon arrival itself. Bede’s calculations famously put the invitation from the British ruler Vortigern around 447. But earlier, near-contemporary hints—the Gallic Chronicle (452), the Life of St Germanus, and archaeological horizons—suggest an arrival closer to the late 420s. If Hengist is active by 428–430, then he was already an adult by that time, likely born around 405—or earlier. Push the calendar forward to the 490s (post-Patrick), and Hengist would be nearing, or over, ninety. It is not impossible for him to have had a son still coming of age then, but it strains the everyday math of the period. A grandson ruling in the 510s makes human sense where a late-borne son ruling so late does not.

Put simply: Bede’s genealogy, the Chronicle’s dates, the Historia’s own chronological aside, and the demographic reality of lifespans in the fifth century all lean in the same direction. Octa is best understood as Oisc’s son and Hengist’s grandson, coming to Kent around or after 512.

What That Does to Arthur’s Dates

Accepting Octa as Oisc’s son nudges the Arthurian timeline forward. If the Historia Brittonum means what it appears to say—that Arthur’s campaigning unfolds “in those days” when Octa assumes command in Kent—then Arthur’s military leadership belongs most naturally to the early sixth century. That dovetails with one cluster of scholarly views that place the climactic Battle of Badon somewhere between the late 490s and the 510s.

Moving Arthur toward the sixth century changes the conversation about material culture and settlement patterns. The archaeology of sub-Roman Britain shows continued occupation in some Roman towns, hillfort reuse in certain regions, and a patchwork of villas falling silent while others flicker on. Continental contacts do not vanish; they warp. A later Arthur fits better with some of the flourishing post-Roman sites and defensive structures that linger into the sixth century. It also squares with the sense—found in later writers like Gildas—that a temporary check was dealt to Saxon advances before a renewed wave in mid-century.

All of that remains circumstantial, of course. Arthur himself is a text-built figure: a title, a set of battle names, an echo in sermons and saints’ lives, a later romance hero who would have startled his earliest chroniclers. But if our only chronological compass for his wars—outside Gildas’s gnomic complaints—is the Historia Brittonum’s sequencing next to Octa, then Octa’s proper placement matters. On balance, the compass points a few degrees later than some popular timelines admit.

The Best We Can Say—And Why It Matters

If we scrape away the varnish and leave only the wood grain of the sources, a conservative picture emerges:

- Octa is most credibly Hengist’s grandson. Bede’s eighth-century testimony is explicit and early: Hengist → Oisc → Octa. That order aligns with the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s regnal dates for Oisc and with the Historia Brittonum’s timing relative to Patrick’s death.

- Octa likely takes Kent after 512. If Oisc’s reign runs 488–512, and Octa follows him, then Octa’s rule belongs to the early sixth century. This also avoids the biologically awkward implication that Hengist fathered a king who then rises to prominence decades after Patrick’s death.

- Arthur’s campaigning belongs most naturally to Octa’s days. Because the Historia introduces Arthur immediately after introducing Octa’s move to Kent, a plausible reading puts Arthur’s wars in or shortly after Octa’s accession. That slides Arthur’s military activity toward the early sixth century—where some independent scholarly arguments already place Badon.

This is not a grand revelation so much as a careful alignment. The earliest evidence does not give us a complete mural; it gives us tiles. Lay them thoughtfully and a coherent mosaic appears.

Why does that matter beyond the chronicle room? Because timelines discipline our imaginations. If we place Octa where the earliest sources most securely put him, we change the frame we hang around Britain’s post-Roman decades. We change which artifacts we relate to which rulers, which church missions map onto which reigns, and how we interpret the rhythm of Saxon expansion and British resistance. In early medieval history, where fixed dates are rare jewels, even a modestly firmer footing can steady the larger story.

More Stories

A Measured Conclusion

King Octa of Kent may never step fully out of the mist. He remains a ruler we glimpse by the light of other men’s pens—Bede, an anonymous British compiler, later monastic chroniclers setting ink to parchment centuries after the fact. But his outline is firm enough for one sound conclusion: the simplest, earliest, and most internally consistent reading makes Octa the son of Oisc and the grandson of Hengist, rising to Kentish rule after about 512.

If we accept that, the often-controversial dating of Arthur’s wars moves with him, nudged toward the early sixth century by the Historia Brittonum’s sequencing. Arthur does not suddenly become more “real,” nor do his twelve battles spring off the page as journal entries. What changes is the backdrop: the kind of Britain in which an extraordinary war leader might plausibly have rallied kings, won a crushing victory, and bought a generation of peace before the tide rolled again.

In the end, Octa’s importance is not in how loudly he strides across the chronicles, but in how quietly he fixes a point on our map. He is the stud in the wall on which we can hang a timeline. And in an age where dates wander and names trade places, that modest certainty—earned by preferring earlier witnesses, aligning internal clues, and respecting human lifespans—may be the most valuable thing a small king can give us.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

The Fifth Labor of Heracles: Cleaning the Augean Stables

Battle Sites of King Arthur Against the Anglo-Saxons

Miranda Kaufman’s Heiresses: A review

The Eye of Horus: What it’s meaning

The Tang Dynasty: Emperor Taizong’s Rise, Conquests, and Legacy

The First English National Lottery: Queen’s Financial Solution

How the Tudors Built Status

Bahay Kubo: A Beloved Filipino Song Reveals Our Globalized Gardens

The Fourth-Century Church: Doctrine, Organization, and the Patristic Legacy

Pope Alexander VI and the Scandalous Borgia Legacy

Royal Family Blood-Marriages in Ancient Egypt

Unveiling the Mysteries of the Lady of the Lake: Arthurian Legend’s Enigmatic Figure