Forget the movie posters. The knight in shining plate and the samurai in lacquered lamellar weren’t just duel-ready icons—they were working cogs in two very different feudal machines. Both fought for lords, swore oaths, and carried lofty ideals. Both also spent a lot of time managing land, paperwork, and politics. Here’s a readable, big-picture look at how knights and samurai actually lived, rose to power, and faded away.

Across medieval Europe and premodern Japan, elites built social orders around professional warriors who served superiors in exchange for status and pay. Knights and samurai shared a similar promise—loyalty and military service for privilege and income—but their worlds shaped them differently.

Knights were heavily armored, usually mounted soldiers who formed a military elite in Europe from the 9th to the 16th centuries. Early on, “knight” meant a capable fighter with a horse and expensive gear. Over time the role hardened into a rank within the nobility, with prestige peaking in the High Middle Ages.

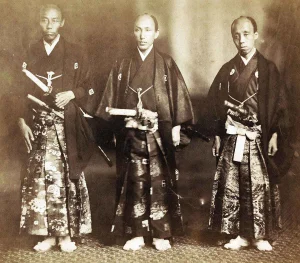

Samurai emerged in Japan from the 9th century and ruled its politics from the 12th to the 19th. Many families traced noble or even imperial lines. A well-bred samurai was expected to wield both culture and steel—captured in the phrase bunbu ichi (“pen and sword as one”).

Ideals: Chivalry vs. Bushidō

Chivalry—literally “things of horsemen”—was a bundle of expectations that tried to civilize a dangerous elite: bravery, loyalty, devotion to lord and faith, and (at least in literature) courtly refinement. The Victorian era later romanticized it into gallantry toward the weak; on the ground, it was more about discipline, reputation, and war-readiness than fairy-tale courtesy.

Bushidō (“the way of the warrior”) began as a practical ethic of skill, courage, and reward in battle—very much a soldier’s code. In the long peace of the Edo period, it absorbed Confucian virtues like filial duty and obedience, stressing service to clan and lord. The stark, death-embracing tone people often associate with bushidō owes much to later writings that looked back nostalgically on a rougher age.

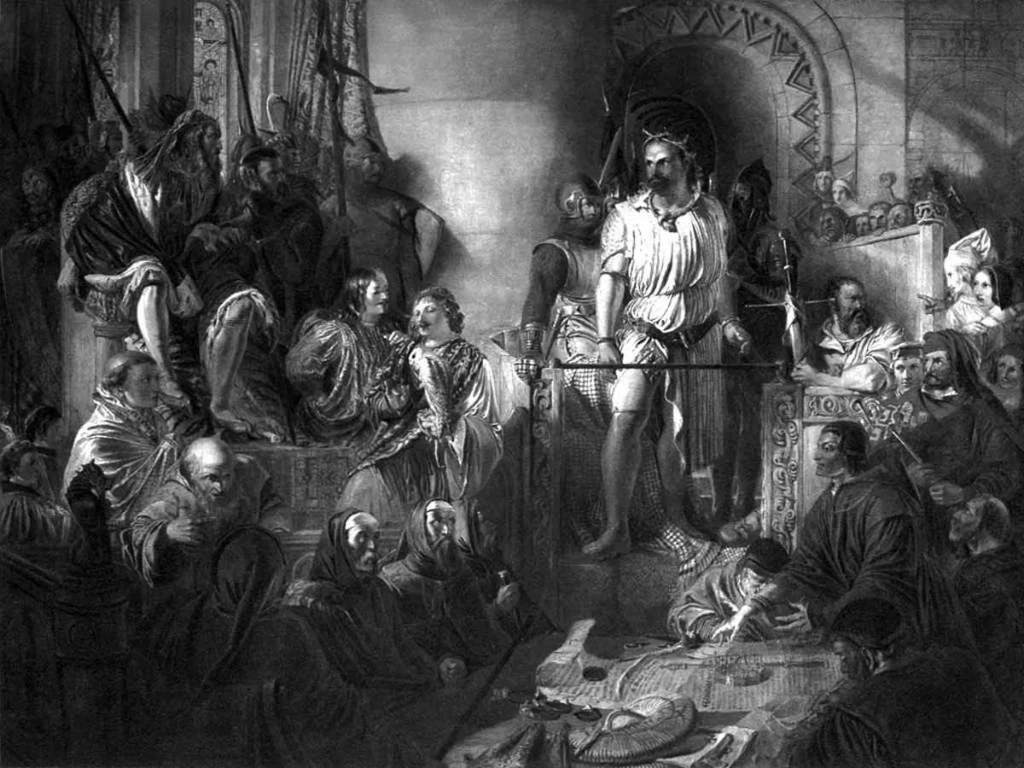

Europe: Under Charlemagne and his successors, rulers rewarded battlefield performance with land and titles. The model spread: fight for your lord, receive estates and status. Religious military orders—Templars, Hospitallers—framed knighthood as a defense of Christendom, adding prestige and purpose.

Japan: As the Heian court struggled to police the provinces, armed specialists—samurai—won appointments, stipends, and marriages into powerful families. The Genpei War (late 12th century) crowned the Minamoto and birthed the shogunate: a military government that ruled while the emperor remained a sacred figurehead.

Knights managed estates, collected revenues, advised lords, and provided armed retinues. The title carried honor, but it also came with chores: court duties, local administration, and mustering troops when called.

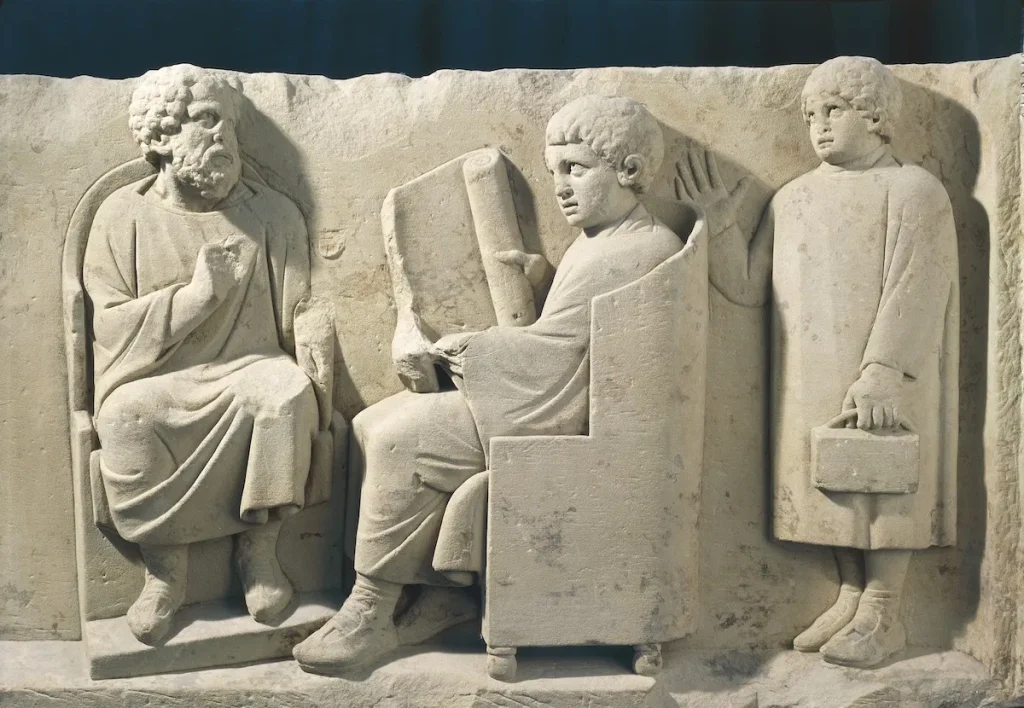

Samurai served in war and in government. As regional lords (daimyō) expanded bureaucracy, samurai staffed offices, kept records, adjudicated disputes, and enforced order. Under the Tokugawa shogunate’s long peace, many became full-time officials wearing two swords—and carrying ledgers.

What They Owed—and to Whom

Feudal bonds ran upward.

- Knights swore fealty, answered military summons, and performed court service. Their code focused on obligations to their lord and peers; peasants generally sat outside the moral frame.

- Samurai literally “served” (saburau). Loyalty to clan and daimyō defined ethics and career. Status could be inherited, granted, or revoked by a lord—another reminder that rank flowed from service.

Knights lived off a “knight’s fee”—land sufficient to support them and their household in exchange for set periods of service. Extra income might come from extended campaigns, ransoms, and local revenues.

Samurai were paid stipends, commonly measured in koku (the annual rice needed to feed one adult). No private estates in the European sense; instead, salary and appointment tied each warrior to a lord’s fiscal base. Loyalty and performance could mean wealthier posts and larger stipends.

How the Role Changed

As warfare evolved, so did identity.

- Knights started as elite fighters and slid toward hereditary nobility—with expectations of courtesy and governance meant to curb excesses.

- Samurai rose as the top legal class in a rigid hierarchy. With national peace after 1600, their swords symbolized authority while their daily work looked increasingly bureaucratic.

Why It Ended

Europe: The Black Death (mid-14th century) shattered the labor market, empowering peasants and fueling urban growth. Cash economies and gunpowder tactics favored paid professionals and mercenary companies. Centralized states built standing armies; the old feudal summons faded, and so did the knight’s military necessity.

Japan: The Meiji Restoration (1868) dismantled the samurai order to modernize the state—abolishing hereditary stipends, centralizing the army, and redefining status under a national conscription system. The samurai ideal persisted in culture; the class itself did not.

The Takeaway

Knights and samurai were more than duelists and poets. They were administrators, revenue managers, and political actors whose prestige rested on organized service. Their codes tried to humanize hard power; their decline followed the rise of stronger states, money economies, and modern armies. The armor dazzles—but the real story is about institutions, paychecks, and public order.