When people think of long-reigning monarchs, Queen Elizabeth II often comes to mind with her seventy years on the British throne. But more than two centuries earlier, another European king ruled even longer. Louis XIV of France, the famous “Sun King,” sat on the throne for an astonishing seventy-two years, from 1643 to 1715.

His reign shaped France, shook Europe, and left monuments—especially Versailles—that still define French grandeur today.

A Child on the Throne

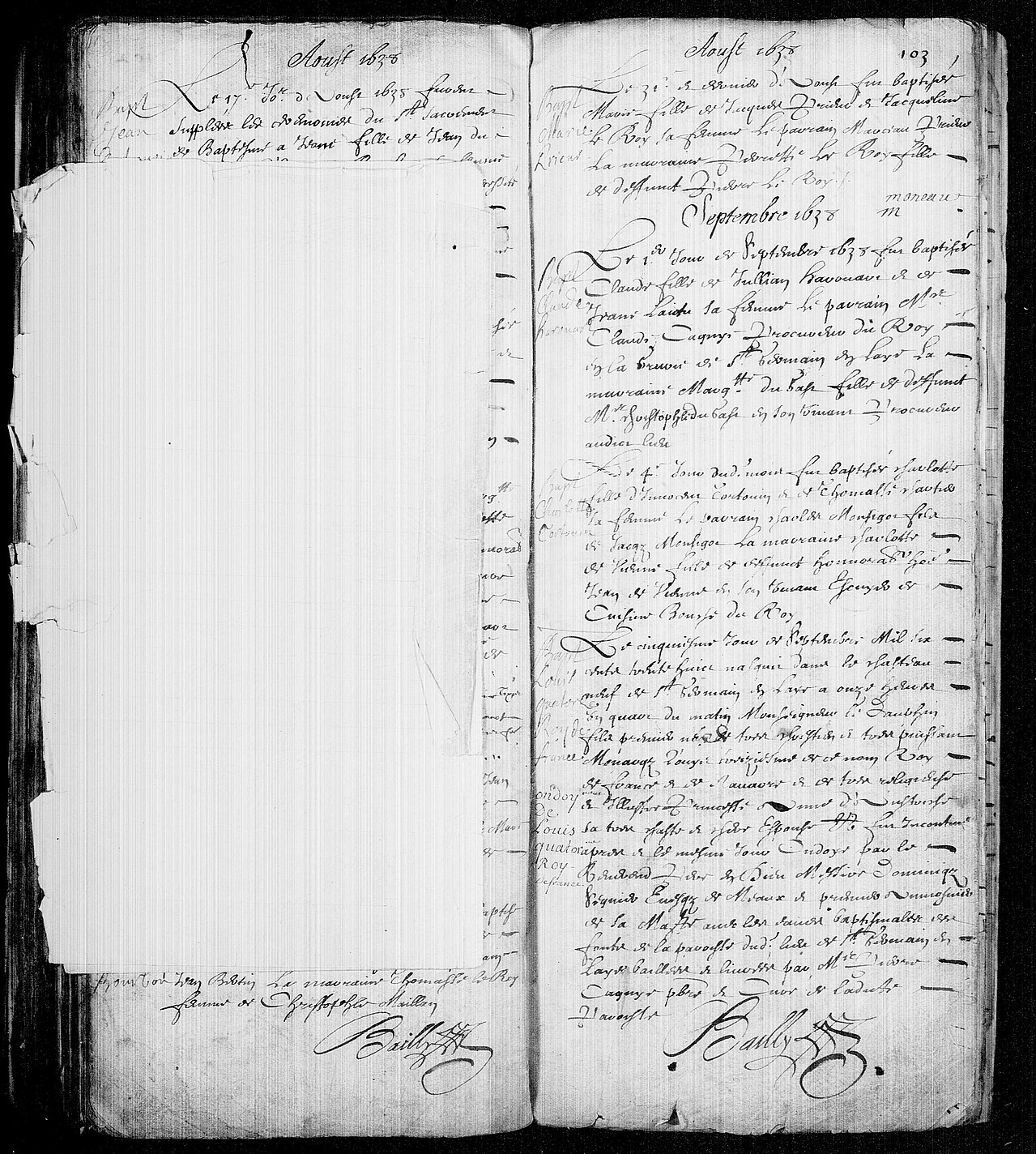

Louis XIV was not born into a peaceful or secure world. His parents, King Louis XIII and Queen Anne of Austria, had endured over twenty years of marriage and numerous stillbirths before finally having him on September 5, 1638. As the long-awaited heir, he was given the title Dauphin and became the focus of immense hope and expectation.

Louis’s relationship with his father was distant, but he was very close to his mother. When Louis XIII died of tuberculosis on May 14, 1643, the boy was just four years old. Overnight, he became King of France.

According to tradition, the new king had to show himself to his subjects. So little Louis was propped up on cushions in a carriage and paraded through Paris. Officials at the Palais de Justice greeted him with all the ritual and formality due to a monarch—but in reality, France would be ruled in his name by adults for many years.

Anne of Austria ignored her late husband’s wishes and took full control as regent. She sidelined some of Louis XIII’s old ministers and kept one crucial figure at her side: Cardinal Mazarin.

Mazarin and a Kingdom in Crisis

Cardinal Jules Mazarin became the chief minister and the real power in France during Louis’s minority. He inherited a difficult situation. France was still deeply involved in the Thirty Years’ War, a brutal conflict that had ravaged much of Europe and claimed millions of lives.

Mazarin helped steer the country through the final negotiations that produced the Peace of Westphalia, which rewarded France with new territories such as Alsace and the bishoprics of Metz, Toul, and Verdun. Diplomatically, France came out stronger.

At the same time, Mazarin guided the young king’s education—not so much in Latin and poetry, but in history, monarchy, and war. Louis was being shaped to rule a powerful modern state.

But the kingdom itself was in trouble. Years of war meant crushing taxes. Bad harvests caused hunger and unrest. Resentment boiled over into a series of uprisings known as the Fronde.

Unlike the English Civil War, which toppled a king, the Fronde failed to overthrow the monarchy. But it left deep scars. The royal family fled Paris at one point; Mazarin even went into temporary exile, directing affairs through letters. Young Louis never forgot how Paris had turned on the crown. This memory would later feed his determination to centralize power and keep the nobility under close watch.

When Mazarin finally died in 1661, Louis was in his early twenties—and ready to rule in his own right.

Louis Takes Control

Louis XIV’s official coronation had been held in 1654 at Reims Cathedral. Crowned with the ancient regalia of French kings, he already embodied centuries of royal tradition. But only after Mazarin’s death did he fully take the reins.

Instead of appointing a new first minister, Louis announced that he would govern personally. Behind this decision was a clear aim: to concentrate power in his own hands. He did, however, rely on talented administrators, chief among them Jean-Baptiste Colbert.

Colbert was a hard-working, detail-obsessed official who helped transform the French state. He:

- Expanded France’s merchant and war fleets

- Improved roads, bridges, and canals

- Reformed policing and aspects of urban administration

- Strengthened royal finances and industry

- Supported arts and sciences, founding academies of Fine Arts, Music, and Science, and promoting the Paris Observatory

With men like Colbert handling the machinery of government, Louis could pursue his twin passions: glory in war and magnificence at home.

War, Glory, and the Cost of Ambition

Louis XIV saw France as destined for greatness and himself as the instrument of that destiny. Much of his reign was marked by warfare intended to expand French influence.

After the death of his Spanish father-in-law in 1665, Louis claimed parts of the Spanish Netherlands, citing his marriage to Maria Theresa of Spain. This claim sparked the War of Devolution (1667–1668). French armies advanced quickly, seizing fortresses and territory, but a Triple Alliance of England, Sweden, and the Dutch Republic forced Louis to accept the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle and pull back.

He soon tried again. The Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678) brought more intense fighting. In the end, the Treaties of Nijmegen granted France Franche-Comté and several fortified towns in the Spanish Netherlands. Smaller campaigns followed, such as the War of Reunions and operations against North African ports like Algiers and Tripoli, as well as the bombardment of Genoa.

Then came the Nine Years’ War (1688–1697), a broad European conflict. Louis launched an invasion of the Rhineland while the Holy Roman Empire was busy fighting the Ottomans, hoping to catch his rivals off guard. Instead, he provoked the formation of the Grand Alliance—a coalition of England, the Dutch Republic, Spain, and the Empire, all determined to stop French expansion.

French forces won notable victories at battles like Fleurus and Landen and fought the English overseas in North America (King William’s War). Ultimately, the Treaty of Ryswick forced Louis to surrender some of his gains, though he kept Alsace.

The last major struggle of his reign was the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), triggered by the death of the childless Spanish king, Charles II. Once again, Europe plunged into a long, bloody conflict over territory and dynastic rights. It ended with the Peace of Utrecht, which confirmed a Bourbon on the Spanish throne but effectively ended Louis’s dream of unchallenged French dominance.

These wars brought moments of glory—but also staggering loss of life and heavy financial strain at home.

An Absolute Monarch

Louis XIV is the textbook example of an absolute monarch. While he relied on ministers like Mazarin and Colbert, he made it clear that ultimate authority rested with him alone.

One of his tools was the system of intendants—royal officials who acted as the king’s eyes and hands in the provinces. Originally an emergency measure in the 1630s, these agents became permanent under Louis. They oversaw tax collection, justice, and local administration, and reported directly to the crown. This weakened the independent power of local nobles and tied the kingdom more tightly to the royal government.

Louis also pushed through reforms in law and order in 1667 and 1670. These reforms:

- Standardized legal procedures

- Improved supervision of courts and prisons

- Required that prisoners be questioned within twenty-four hours

Steps like these helped make justice more uniform across France, even if the system still favored the wealthy and powerful.

At the same time, Louis’s style of rule had a harsh side. He tolerated little dissent and expected obedience from both nobles and commoners. The image of the king as the unchallengeable center of power was no accident—it was carefully cultivated.

Faith and Intolerance: The Huguenots’ Fate

Religion was another arena where Louis asserted firm control.

In 1598, the Edict of Nantes had granted limited rights and protections to French Protestants (Huguenots), ending the Wars of Religion that had torn France apart in the 16th century. For decades, this edict allowed a fragile coexistence between Catholics and Protestants.

Louis XIV ultimately decided this was incompatible with his vision of a united, Catholic kingdom. In 1685, he revoked the Edict of Nantes. Protestant churches were closed or destroyed; schools were shut; and Huguenots were pressured to convert, often under threat of imprisonment.

Faced with persecution, around a quarter of French Protestants chose exile instead. Many fled to England, the Dutch Republic, Prussia, and the American colonies, taking with them skills, capital, and networks that had previously benefitted France. This is one of the most heavily criticized decisions of Louis’s reign and a stark example of how religious intolerance can damage a country in the long run.

Versailles: A Palace and a System

If Louis XIV left one undeniable masterpiece behind, it is the Palace of Versailles. Construction on a grand scale began in 1661 and continued for more than fifty years, employing tens of thousands of workers.

Versailles was more than just a luxurious residence. It was a political machine. By drawing the nobility to live at court, keeping them busy with ceremonies, etiquette, and court life, Louis effectively turned potential rivals into courtiers dependent on his favor.

The palace dazzled visitors:

- The King’s Grand Apartments

- The glittering Hall of Mirrors

- Rich tapestries, oriental carpets, gilded furniture, and crystal chandeliers

- Vast gardens with lakes, fountains, flowerbeds, and carefully trimmed hedges

Life at Versailles could not have been further from the hardship faced by peasants who struggled under taxes and bad harvests. Court society was filled with balls, operas, plays, feasts, and endless gossip and intrigue. Writers, musicians, and performers were drawn into the orbit of the court, making Versailles a cultural as well as political center.

To many contemporaries, Versailles seemed almost like another world—some even called it the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” It was the ultimate expression of the Sun King’s vision of royal magnificence.

Death and Legacy

Louis XIV died at Versailles on September 1, 1715, just four days before his seventy-seventh birthday. He had been king for seventy-two years—longer than almost any other monarch in European history. Having outlived his son and grandson, he was succeeded by his great-grandson, the future Louis XV.

His legacy is deeply mixed.

On the negative side:

- His wars drained France’s treasury and cost countless lives

- His persecution of Protestants weakened the country’s economic and intellectual base

- His insistence on control and display contributed to a growing sense of resentment among ordinary people

On the positive side:

- He strengthened the central state and made administration more efficient

- He left behind legal and institutional reforms that outlasted his reign

- He presided over a brilliant cultural era in art, architecture, literature, music, and science

- He created Versailles, a symbol of French art and power that still captivates millions

Louis XIV was far from a saint. He was ambitious, often ruthless, and sometimes blind to the suffering his policies caused. Yet his reign remains one of the most important and fascinating chapters in French history—a period when a single man tried to make himself the sun around which an entire kingdom revolved.