At the turn of the 20th century, Northeast Asia stood on a fault line. Empires were shifting, railways were ribboning across contested frontiers, and resource maps mattered as much as political ones. In this tense landscape stood Manchuria—vast, iron-rich, timber-laden, and threaded with fertile soil and strategic rail lines. For the Japanese Empire, fresh from victories in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), Manchuria promised both wealth and leverage. For a fractured China, wracked by warlord rivalries and a weak central authority, it was a vital heartland slipping through its grasp.

Japan’s South Manchuria Railway became the physical symbol of these clashing ambitions. It wasn’t just steel and sleepers; it was an artery for coal and grain, a corridor for troops, and a statement of imperial intent. Stations and depots doubled as offices of influence, and every mile of track knit Tokyo’s interests tighter to the region. As the 1920s closed, Japan’s industrial machine demanded more fuel, more ore, more certainty. Manchuria looked like the answer.

China, meanwhile, faced a cruel arithmetic. Unifying the nation meant balancing rival generals, strengthening institutions, and resisting foreign encroachment—tasks that would test any state, let alone one battered by civil strife. The Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek prioritized internal consolidation and communist suppression, leaving the northeastern frontier thinly defended and politically brittle. In the gap between Japan’s hunger and China’s turmoil, the stage was set.

Nightfall in Mukden

On the evening of September 18, 1931, near the city then known as Mukden—today’s Shenyang—a small explosion rattled a section of the South Manchuria Railway. The blast was minor. A scheduled train crossed the damaged track without catastrophe. There were no bodies, no toppled carriages, no smoking craters to demand vengeance.

But what the explosion lacked in destruction, it possessed in utility. Within hours, officers of Japan’s Kwantung Army—stationed in Manchuria to protect Japanese interests—declared the blast an act of Chinese sabotage. Troops surged from their barracks, armored cars growled across darkened streets, and Japanese units fanned out to seize junctions, depots, and government buildings. The operation moved with startling speed, as if a script had been rehearsed.

In the years since, evidence has consistently pointed to a grim conclusion: elements within the Kwantung Army orchestrated the blast themselves. Colonels Seishirō Itagaki and Kanji Ishiwara—true believers in expansion—appear to have engineered a provocation that would justify the invasion they desired. The match was small, but the tinder was everywhere. In the silent minutes after the detonation, Manchuria’s fate shifted.

The official narrative thundered forth: Japan had been attacked; Japan must respond. Yet the facts on the ground told a quieter story. The railway was only superficially damaged. No one had died. And still, by dawn, Mukden was under Japanese control, its barracks disarmed and its nerve centers occupied. Surprise carried the day; planning carried the rest.

The Lightning Conquest

Once Mukden fell, the dominoes followed. Japanese forces rolled north and east, locking down Changchun, Jilin, and the critical rail hubs that stitched Manchuria together. Columns moved like clockwork, stepping from town to town along lines the army knew intimately thanks to years of “protection” work for the railway. Within days, the map had changed.

Chinese resistance was brave but scattered. Warlord politics had carved the northeast into competing fiefs, and communication with Nanjing was strained. Chiang Kai-shek’s government faced a bitter triage: fight a better-prepared foreign army on distant ground, or consolidate power in China’s core against domestic threats. The result was hesitation and patchwork defense. Unit by unit, city by city, the advantage tilted toward Tokyo.

The speed of the occupation sparked a crucial suspicion at home and abroad: the Kwantung Army had prepared not merely for retaliation, but for conquest. Warehouses yielded carefully stored supplies; rail schedules aligned perfectly with troop movements. The “incident” looked less like an unexpected attack and more like a door blown open at the exact moment the invaders were ready to step through.

By early 1932, Japan’s control of Manchuria was a matter of fact. Garrisons guarded train yards. Administrative buildings flew new flags. Patrols sought out holdouts while engineers surveyed new routes. In the wake of the soldiers came a different army—planners, managers, and propagandists—tasked with converting a seized territory into a showcase of imperial ambition.

The World Watches—and Shrugs

China appealed to the conscience of the world. The League of Nations, built in the aftermath of World War I to keep peace by collective will, dispatched the Lytton Commission to investigate. Months passed. Delegations toured rails and barracks, interviewed officials, and drafted a careful report. When the commission finally published its findings in October 1932, they were damning: Japan’s invasion was unjustified; the Mukden blast did not warrant the seizure of an entire region.

Moral clarity met political paralysis. The League could urge, but not enforce. It could condemn, but not compel. Sanctions, if any, were weak. The great powers were mired in the Great Depression, skeptical of distant commitments, and wary of provoking new wars. In early 1933, Japan simply left the League—an exit and an announcement rolled into one: the old rules could be ignored.

Across the Pacific, the United States struck a principled, if toothless, note. Secretary of State Henry Stimson declared that the U.S. would not recognize territorial changes achieved by force—a policy soon known as the Stimson Doctrine. It drew a line on paper that soldiers had already crossed on the ground.

The lesson was not lost on Tokyo—or on other ambitious regimes. Italy and Germany watched the world’s hesitations and drew their conclusions. If a determined power seized what it wanted quickly enough, international censure might be survivable. Manchuria became not just a conquest, but a case study in the limits of 1930s diplomacy.

Propaganda and Puppet States

Conquest is never only about guns and gates. It is also about stories—who tells them, who believes them, and who is forced to live under them. In the months after the Mukden Incident, Japan’s information machine shifted into high gear. Newspapers lauded a “police action” to restore order. Newsreels framed the occupation as a civilizing mission: railways humming, factories rising, bandits banished, commerce blooming. The invaders posed as guardians and builders, protectors of stability and partners in prosperity.

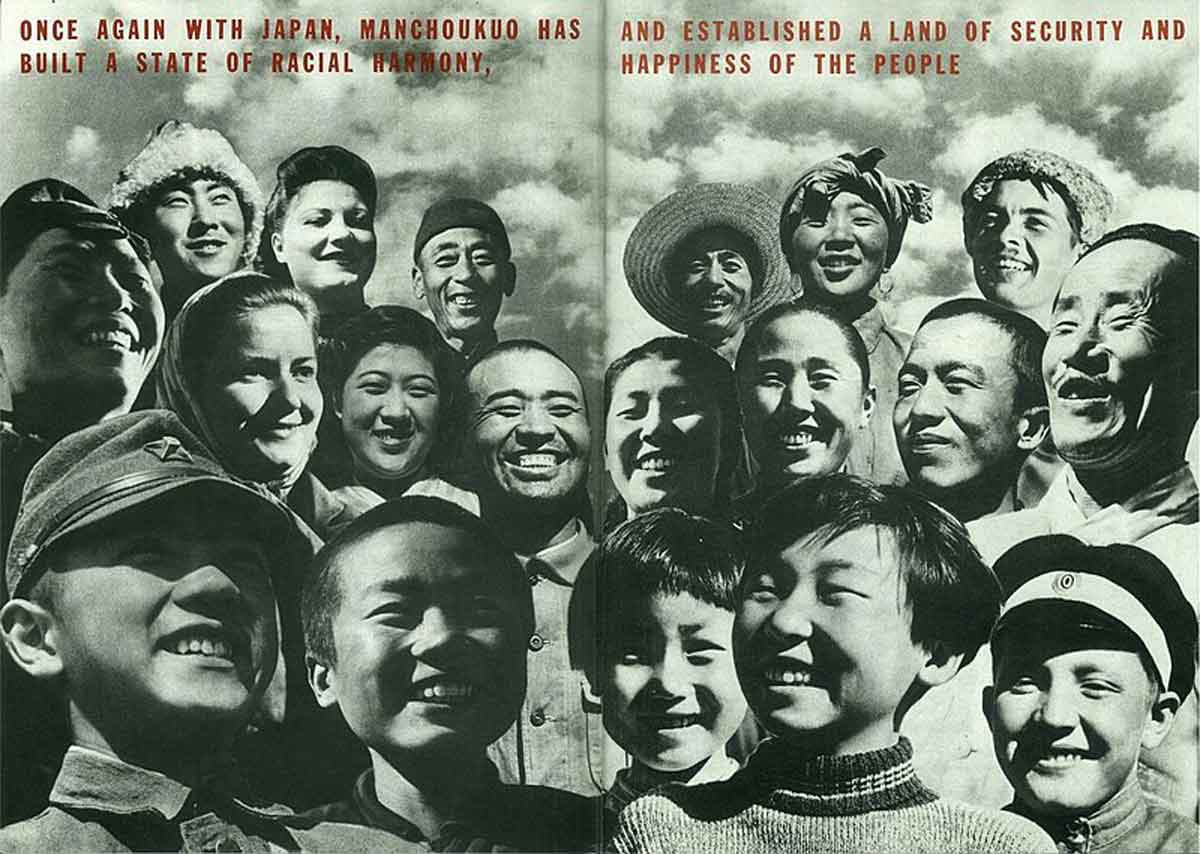

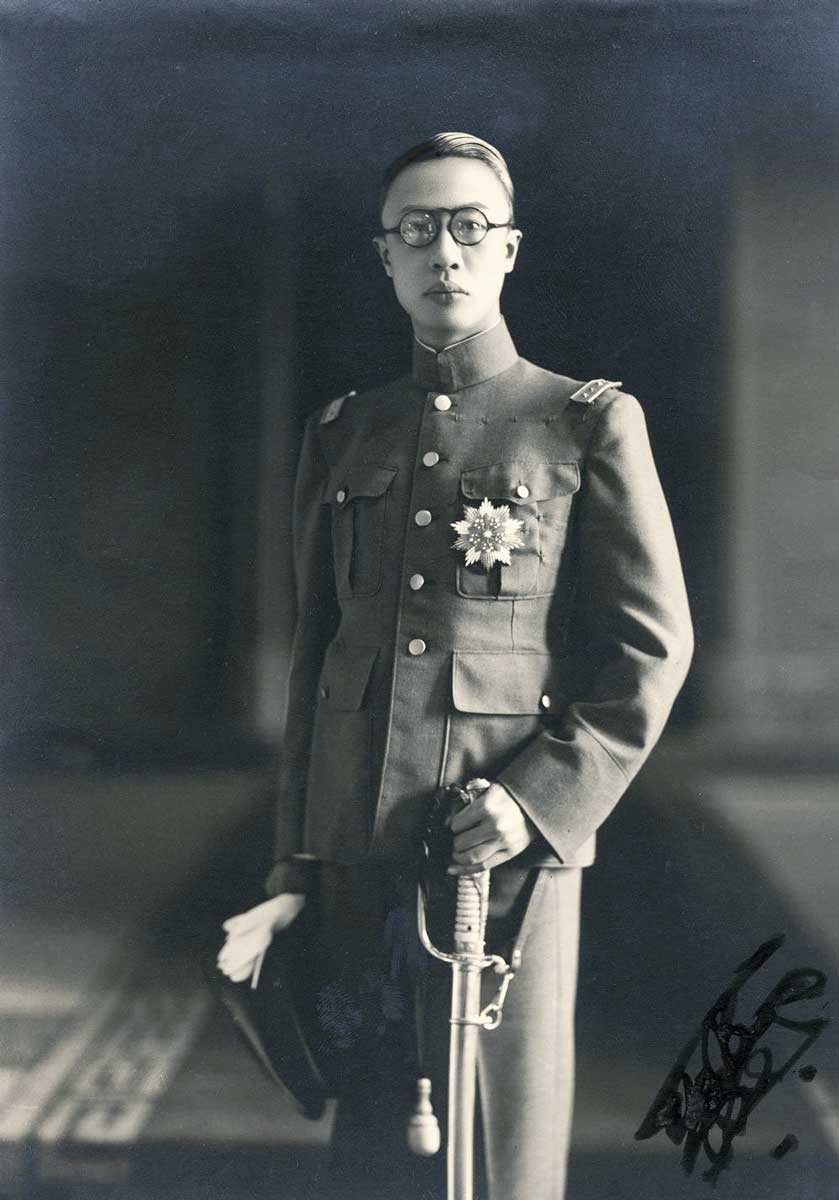

At the center of this narrative was a new entity: Manchukuo. In 1932, Japan declared the birth of this “independent” state, elevating the last Qing emperor, Pu Yi, as its figurehead. The arrangement, cloaked in ceremonial pageantry, offered an illusion of legitimacy. In reality, decisions flowed from Japanese officers and advisers. Manchukuo’s ministries were facades; its sovereignty, a stage prop.

Propaganda painted Manchukuo as a multiethnic utopia—Manchus, Mongols, Han Chinese, Koreans, and Japanese living under a benevolent order of “harmony.” Posters beamed with sunbursts and modernist slogans. Schoolbooks spoke of progress, duty, and destiny. The rails and roads that Japan laid across the landscape were billed as gifts; the mines and mills as engines for shared wealth.

On the ground, harshness told the truer story. Land and labor were redirected to serve imperial needs. Resources flowed outward. Resistance met reprisals. Security organs tightened their grip, and ordinary people navigated a new reality where a wrong step could mean disappearance. Industrial growth came, to be sure—Manchuria’s production surged—but its benefits were structured to feed Japan’s expanding war economy.

China’s counternarrative was equally clear and, in its essentials, truthful: Manchukuo was a puppet, the invasion an act of aggression, the “harmony” propaganda a veil for domination. Yet internal divisions and battlefield setbacks hampered the spread of that message at home. The Nationalist government struggled to translate outrage into organized resistance, even as grassroots anger and local uprisings simmered.

Echoes and Aftershocks

History rarely ends with a single explosion. The Mukden Incident did not simply change Manchuria; it accelerated the slide toward a wider conflagration. The Kwantung Army, emboldened by its swift success and the world’s inability to reverse it, pressed farther. Frontier clashes multiplied. In 1937, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident near Beijing ignited the Second Sino-Japanese War in earnest—a brutal struggle that would merge, by 1941, into a global war once Japan struck Pearl Harbor.

For China, the loss of Manchuria was a wound that bled for years. Economically, it stripped away resources and industry that might have financed national reconstruction. Politically, it exposed the state’s weakness just as it needed strength most. Yet the occupation also catalyzed something the aggressors did not intend: a hardened Chinese nationalism. Intellectuals wrote, students marched, soldiers fought, and citizens endured. The narrative of victimhood became a rallying cry for resistance and, later, for remembrance.

Internationally, the League’s failure in Manchuria sounded a quiet knell for the old order. Treaties proved fragile when not backed by collective power. Investigative commissions, however honest, could not substitute for credible deterrence. In the 1930s, authoritarian regimes learned how to move faster than the world could convene. By the time the papers were written and the speeches delivered, new lines had been drawn on the map.

The military men behind the Mukden Incident paid differing prices in the postwar reckoning. But accountability for individuals, important as it is, cannot reverse what their decisions unleashed—cities burned, families shattered, millions uprooted. The reverberations of that September night still echo in regional memories and diplomatic caution today. Northeast Asia’s security architecture, its alliances and anxieties, carries the imprint of rails laid for commerce and used for conquest.

The Small Blast That Changed a Continent

It is tempting to look for dramatic causes behind great events—thunderclaps of history that announce themselves as turning points. The Mukden blast was not that. It was a small charge placed by men who wanted a pretext. Its power lay not in its force, but in the readiness around it: armies positioned to move, bureaucracies set to govern, factories waiting to roar, and a world too distracted or divided to stop them.

Yet within that bleak calculus, there is a lesson about the fragility of order and the weight of choices. The South Manchuria Railway was an iron line across contested soil, but it was also a metaphor: technology and modernity can serve prosperity or predation, depending on who controls the switches. Propaganda can cloak plunder as progress. Puppet states can mimic sovereignty while hollowing it out.

And still, people resist. In occupied towns, families hid fugitives. Workers slowed their pace. Guerrillas mapped the forest paths. Writers kept forbidden journals. Students whispered banned songs. These small acts did not immediately overturn a conquest, but they preserved a moral ledger that history would later consult.

When we name the Second Sino-Japanese War, when we tally World War II’s Pacific horrors, the Mukden Incident sits near the beginning of the ledger. It showed how quickly borders can change when ambition meets opportunity; how feeble international admonitions sound without enforcement; and how narratives—carefully crafted, relentlessly broadcast—can smooth the path for tanks and trains alike.

A century on, the memory of Manchuria’s seizure is not only about what was taken, but about what it foreshadowed. It warns against complacency in the face of creeping faits accomplis. It argues for institutions that can act as well as speak. And it asks us to scrutinize the stories we are told when power seeks expansion behind the mask of security and development.

In Mukden, the night of September 18 began with a muted thump on a railway embankment. By morning, an empire had accelerated. By year’s end, a puppet state stood where a province had been. The world had watched—uneasily, ineffectively—as a small explosion opened a much larger war. That is the pretext’s cruel genius: the lie is small, the consequences enormous. Remembering that dissonance is part of remembering Manchuria.