In the middle of the twentieth century, the map of Latin America looked like a mosaic glazed with generals’ uniforms and the polished shoes of oligarchs. North of that mosaic stood the United States—watchful, well‑funded, and willing to bankroll allies who promised to keep communism at bay. For ordinary people from Guatemala to Chile to Nicaragua, that bargain had a price: censored newspapers, vanished neighbors, and states that behaved like private estates.

Then 1959 happened. The Cuban Revolution broke the spell of inevitability, and the possibility of another way sped through the region like rumor on market day. In Nicaragua, it took years for that rumor to ripen into revolution. But by the 1970s, a movement with many faces and one name—the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN)—had found its footing.

A Dynasty in Uniform: The Somoza Era

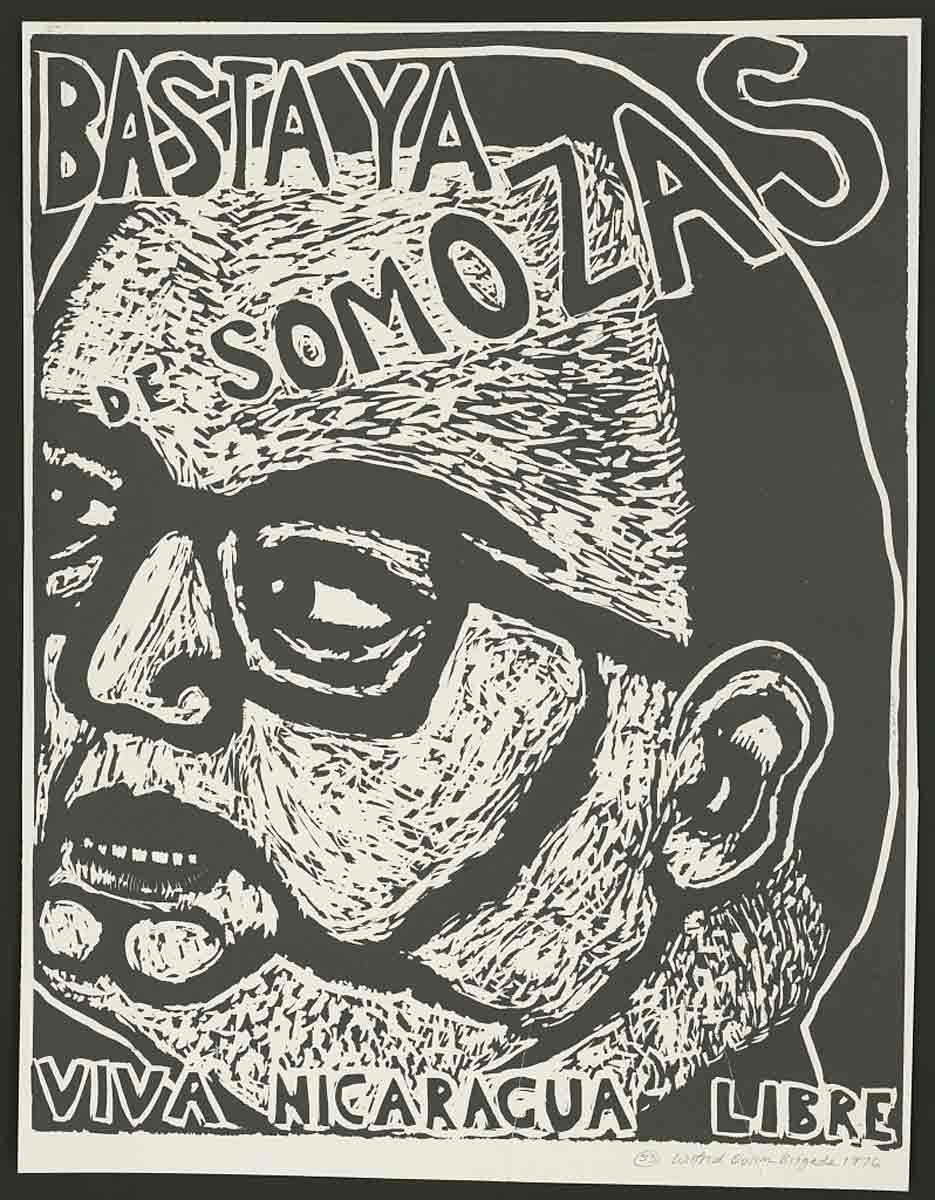

Nicaragua in the late twentieth century was, in practice, a family business. Anastasio Somoza García seized the presidency in 1937 and built a regime that outlived him. His sons—Luis Somoza Debayle and Anastasio Somoza Debayle—took turns at the top, using the National Guard to police dissent and the state to accumulate land, companies, and influence. Elections were staged; opposition parties existed but only within safe, supervised boundaries. Beyond the stage lights, ballot boxes were stuffed and critics found themselves threatened, jailed, or worse.

The Somozas’ rule rested on two pillars: patronage at home and partnership abroad. Domestically, they distributed favors to elites and foreign firms willing to play by the family’s rules. Internationally, they offered something Washington valued more than scruples: a firm anti‑communist ally and a launchpad for covert operations in the neighborhood. The bargain brought dollars and weapons; it also deepened resentment.

By the 1960s, as strikes flickered and student groups organized, a new kind of opposition began to coalesce. Inspired by anti‑imperial ideas and the Cuban example, the FSLN was founded in 1961 by Carlos Fonseca, Silvio Mayorga, and Tomás Borge, then exiles in Honduras. Their goal was simple to say and perilous to pursue: end the Somoza regime and refound Nicaragua on more egalitarian terms.

After the Tremor, a Shift: Managua, 1972

On a December night in 1972, the earth itself seemed to take sides. An earthquake ripped through Managua, toppling buildings and killing thousands. The world sent aid. Much of it vanished into the pockets of the very people charged with relief. As the rubble settled, so did a bitter understanding across class lines: the regime would even plunder catastrophe.

New “emergency” taxes arrived. Contracts flowed to friends. Businesses chafed; church leaders spoke more plainly; the press—where it could—reported with a sharper edge. Many Nicaraguans didn’t share the FSLN’s socialist ambitions, but outrage is a unifier. A broad coalition of unions, students, professionals, campesinos, and disillusioned elites slowly formed around a basic agreement: the Somozas had to go.

In the countryside, the FSLN expanded recruitment. In the cities, strikes and demonstrations multiplied. By 1974, the movement was bold enough to seize a group of well‑connected officials and demand prisoner releases and other concessions. The government’s response was a blunt instrument: an indiscriminate counterinsurgency that punished communities suspected of sympathy. The violence scandalized segments of the Catholic Church and attracted international attention, reshaping how the world saw the regime.

Then came a galvanizing martyrdom. In 1978, the assassination of Joaquín Chamorro, a prominent newspaper editor and critic, made it clear that moderation would not be repaid with mercy. Protests swelled. The regime declared martial law, shuttered outlets, and unleashed the National Guard. Each attempt to seal the lid only built more steam beneath it.

Three Currents, One River: Inside the FSLN

Even as the opposition grew, the Sandinistas themselves were not monolithic. Over the 1970s, three main factions took shape, all committed to toppling Somoza but disagreeing on tempo and tactics—some emphasizing prolonged guerrilla struggle, others urban insurrection or broader alliances. The differences mattered on the ground, but as unrest widened and the Guard overreached, those streams converged. By decade’s end, the FSLN’s strength lay less in ideological purity and more in its ability to knit together teachers and truck drivers, peasants and priests, shopkeepers and soldiers frightened of their orders.

1979: The Capital Encircled

By 1979, the regime’s pillars were cracked. A ruined economy—strikes, capital flight, and the costs of repression—left the treasury bare. Foreign patrons kept their distance. The FSLN controlled most of the country and had announced a provisional Junta de Gobierno de Reconstrucción Nacional to steady life in liberated areas. Even the Guard, long the regime’s iron fist, was fraying under losses and defections.

In July 1979, Sandinista forces surrounded Managua. The Somozas fled. Crowds poured into the streets. The fireworks of victory were real, but so was the sobering dawn. A war had ended. A different kind of struggle was about to begin.

More Stories

Governing the Morning After

The new government tried to be what it said it was: a coalition. Sandinistas dominated, but the leadership included non‑FSLN figures to reassure citizens that Nicaragua would not swap one closed circle for another. Diplomatically, Managua signaled openness to the United States and others across the political spectrum, wary of isolation and eager for reconstruction funds. This was not the hour to burn bridges.

The scale of the task was staggering: 50,000 dead, 600,000 homeless, infrastructure shattered, productive capacity drained. In a pragmatic first step, private‑sector representatives were enlisted to help renegotiate debt and secure aid. At the same time, the government began to deliver on the social promises that had drawn the poor to the revolution. Land seized and hoarded by the Somozas was nationalized and redistributed to cooperatives. Spending on health and education surged. Clinics opened, schools multiplied, and teachers—thousands of them—were trained for a sweeping literacy crusade that would earn praise, including from UNESCO.

But governing coalitions are ecosystems; remove certain species and balance wobbles. As the Sandinistas consolidated control—holding a majority in representative bodies and commanding the key ministries—moderate allies peeled away. Without those counterweights, the state moved further and faster than some Nicaraguans could accept: deeper confiscations, warmer ties with Cuba and the USSR, and less emphasis on competitive elections than on mass organizations and “popular power.” Support remained strong among the revolution’s base, but disquiet grew in the middle and upper strata—and in foreign capitals.

A New Enemy with Old Friends: The Contras

If the Carter administration had tried to hedge its bets—cutting Somoza loose and seeking constructive ties with the Sandinistas—the Reagan administration chose confrontation. Accusing Managua of aiding revolutionaries in El Salvador and marching toward one‑party rule, Washington cut aid and began organizing a “low‑intensity” war designed to bleed the new regime: economic strangulation, political isolation, and, most consequentially, financing, arming, and training a counterrevolutionary force known as the Contras—a mix of former National Guardsmen and other opponents.

An invasion was off the table; a proxy war was not. The Contras hit roads, cooperatives, clinics, and outposts. The Sandinista state diverted more budget and attention to defense, starving the very social programs that had lifted hope. The U.S. embargo tightened screws on trade. To survive, Nicaragua leaned harder on Soviet and Cuban assistance—proof, in Washington’s eyes, that Managua was exactly what it feared.

Inside the country, an embattled government made familiar mistakes. Under siege, it restricted press freedoms and harried opposition groups it saw as Trojan horses. To supporters, these moves were wartime necessities; to critics, they looked like the habits of the old regime in revolutionary colors.

Elections in a Time of War

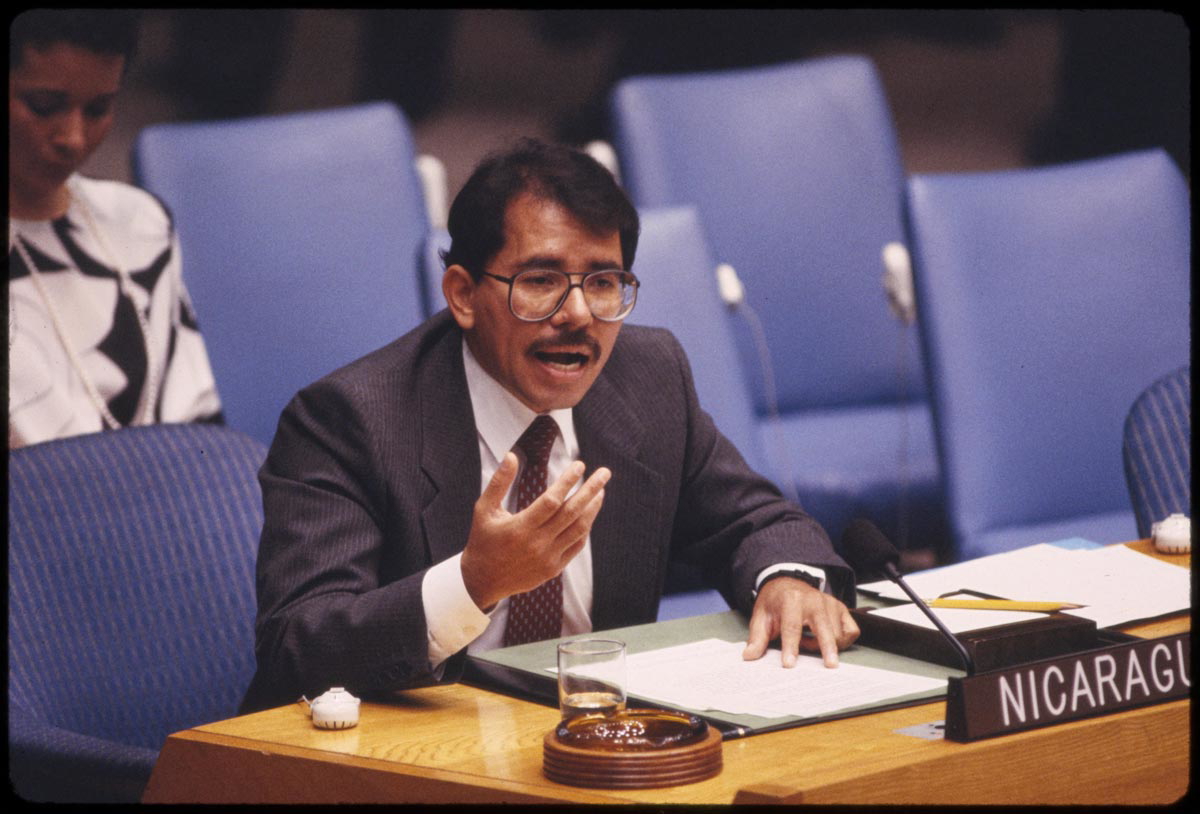

Trying to pry open diplomatic doors and legitimize its course, the government held elections in 1984. Right‑wing parties boycotted. U.S. officials declared the process tainted before ballots were cast. Still, turnout was high, and Daniel Ortega, a leading figure of the FSLN, won the presidency. The FSLN secured a majority in the National Assembly, giving it the leverage to continue its social agenda even as war gnawed at the edges.

Internationally, the vote changed few minds. The conflict intensified. Villages braced for night attacks; mothers kept their children closer. Economically, the country staggered under shortages and hyperinflation fueled by embargo and war. Strategically, the Sandinistas faced a narrowing corridor: bend and lose revolution; stand firm and risk losing the country.

Then Hurricane Juana struck in 1988, leaving 180,000 people homeless. The state, already strained past its limits, could not absorb another blow. Public patience thinned.

1990: A Different Kind of Victory

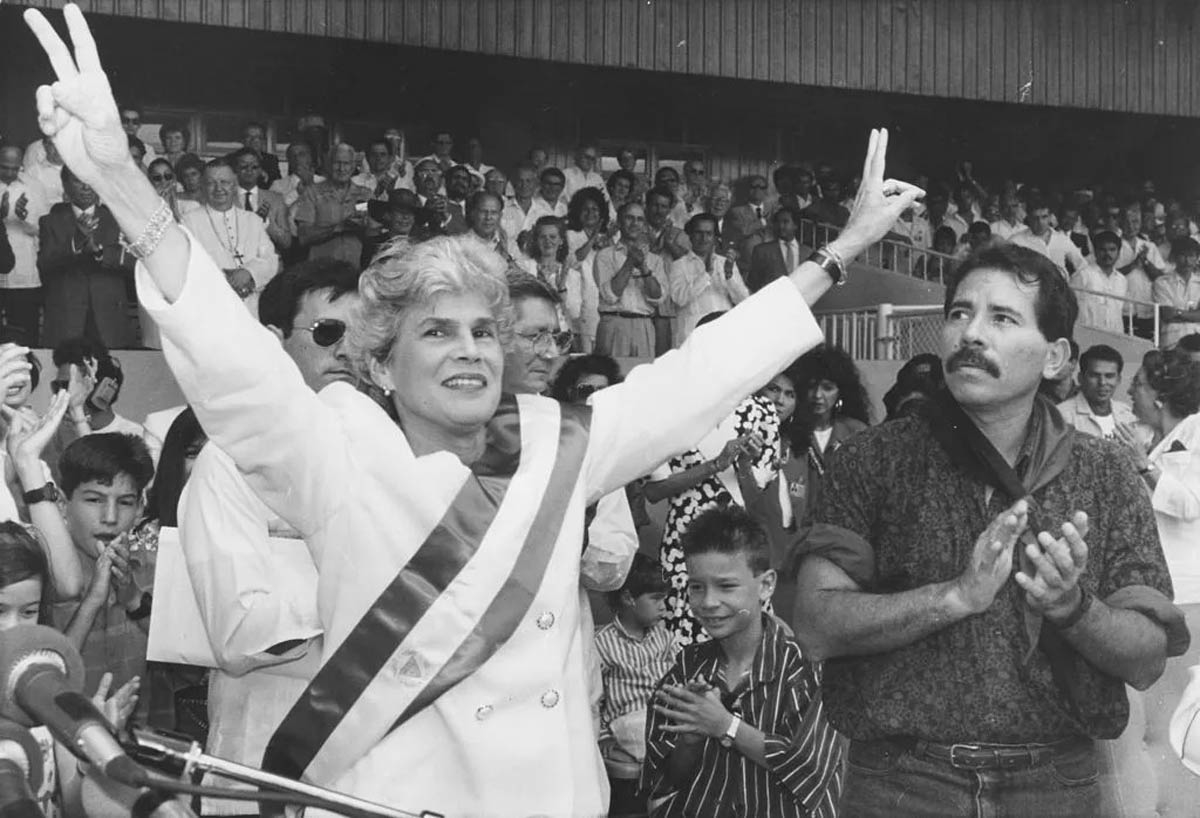

The elections of 1990 were not a plebiscite on ideology so much as a referendum on war. Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, the widow of the slain editor and a former member of the early post‑Somoza junta, led a broad anti‑Sandinista coalition stitched together with U.S. support. She offered a simple trade: vote for us, and the war will end.

Nicaraguans did. International observers judged the vote free and fair. And then something quietly extraordinary happened: the Sandinistas accepted defeat, handed over power, and took their seats as an opposition in a multiparty democracy. In a region where so many rulers delayed, denied, or defied electoral verdicts, Nicaragua’s peaceful transfer was a notable break with precedent.

The revolution, in one sense, was over. In another, it had simply entered a new chapter.

The Afterlives of a Revolution

Even early on, the FSLN made life better for many—especially in classrooms and clinics. But the counterrevolution and embargo narrowed the space for progress and hardened habits of control. By the late 1980s, the state that promised liberation too often acted besieged. That tension—between emancipatory aim and coercive means—would shadow the country long after 1990.

Politics, like rivers, circle back. The Sandinistas returned to the presidency in 2006 under Daniel Ortega, whose government remains in power today. The hopes and contradictions of the 1980s echo across the present: questions about participation and pluralism, about social justice and economic stability, and about the shadow cast by a powerful neighbor whose policies shaped the field on which Nicaraguans fought and voted.

What Nicaragua’s Revolution Teaches

From a distance, the arc seems clean: dynasty → insurrection → victory → counterrevolution → election → alternation. Up close, it is messier and more human. Three themes emerge.

1) Coalitions win wars. The FSLN did not triumph because it was doctrinally pure. It won because it made room—sometimes uneasy room—for workers and priests, urban youth and rural cooperatives, radicals and reformers united by the conviction that the Somoza regime had to end. Broad alliances build momentum. They also sow the seeds of later strain when the guns quiet and interests diverge.

2) Governing is a second revolution. Overthrowing a dictatorship is a feat; rebuilding a state is a lifetime. The Sandinistas showed that the right to read and the right to a clinic could be delivered in short order. They also learned that war is a greedy creditor, collecting payment in budgets and liberties alike. A state besieged risks becoming a mirror of what it once opposed.

3) Great powers write in the margins. The United States withdrew support from a dictator it had long backed, then armed those who took up arms against his successors. Its embargo and covert strategies shaped life on Nicaraguan streets as surely as any domestic decree. None of that erases Nicaraguan agency; it simply acknowledges the weather they fought in.

Climax and Coda

If the climax of Nicaragua’s revolutionary story came in July 1979, when Somoza fled and crowds reclaimed Managua, the coda came in February 1990, when a different crowd lined up calmly at polling stations and chose an end to war over continuity in power. In their own ways, both moments were declarations of sovereignty: the first against a family that treated a nation as inheritance, the second against the logic that bullets must always be answered with bullets.

The years between were full of courage and compromise, triumph and tragedy. Literacy brigades hiked into mountains with chalk and notebooks. Mothers kept vigil for sons lost to ambushes on dark roads. Farmers received titles to plots they could finally call their own. Newspapers went quiet, then noisy, then quiet again. Governments in Washington and Moscow ran their fingers along maps. Weather did its old cruel work.

And yet, through all of it, Nicaraguans kept making choices—about what to demand, whom to trust, where to draw lines. That is the stubborn miracle of the story: not that a dynasty fell, or that a rebel flag flew over the capital, but that a people, bruised and divided, could still pass power with ballots when the moment came.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Top 6 Latin American Writers in History

Ancient Greek Wisdom Back to Europe through Crusades

Nestor Makhno: The Ukrainian Anarchist

Machiavelli, Luther, and the Rise of Modern Moral Thought

Sir Thomas More: Why He Became Tudor England’s Most Controversial Man

The Second Reform Act of 1867: What Really Changed in Britain

Saint Patrick: The Life and Legends of Ireland’s Patron Saint

The Tragic Wisdom of Croesus in Herodotus’ Histories

Three Ancient Egyptian Tombs Unearthed in Luxor

Absinthe: From Green Fairy to Moral Panic

Ulysses S. Grant: Shy Farm Boy, Reluctant Soldier, Relentless Leader

How American Lend-Lease Trucks Fueled the Soviet War Machine in WWII