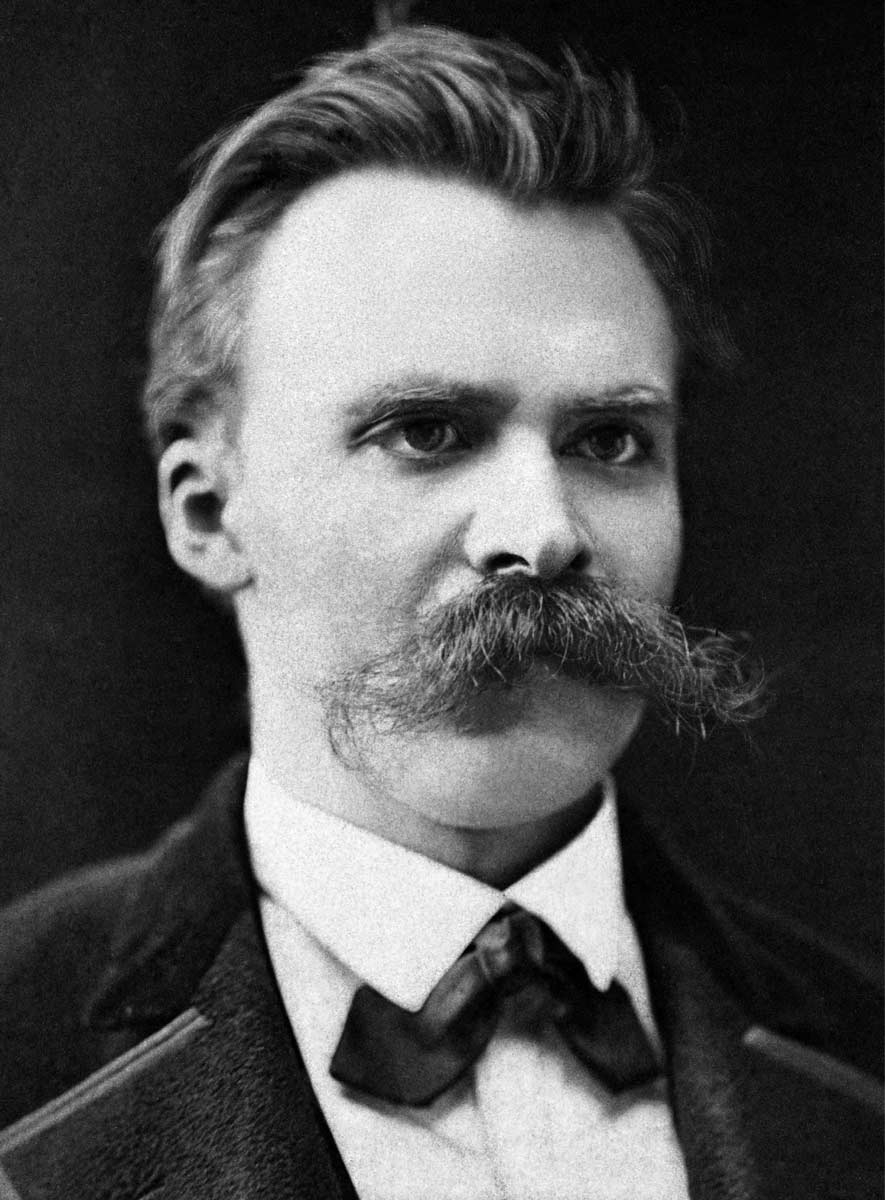

Imagine sitting in a crowded lecture hall in 1872 and hearing the speaker calmly argue that most people should not be educated. Not “university isn’t for everyone,” but something much sharper: only a tiny minority deserve true education, the masses should be kept away from it, and trying to educate them is dangerous for the state.

That was Friedrich Nietzsche, then a young professor at Basel University. The surprising part is not just what he said, but how people reacted: his five public lectures on education were a hit. The hall was full every night.

These talks later appeared in English under the title Anti-Education. The title sounds like Nietzsche is against learning altogether, but that’s not quite right. He isn’t against education as such; he is against what passes for education in his time and, by extension, in ours too.

Nietzsche’s Ideal of “True Education”

For Nietzsche, real education is not a mass project. It is something rare and severe, meant only for those with the potential for genuine genius and delivered only by geniuses. He pictures the ideal teacher as someone who leads the student by one hand, while the other reaches back into the past to clasp “the saving hand of the Greek genius.” True education, in his mind, stands in a living relationship with the highest achievements of classical Greece.

This is not a matter of curriculum design or exam systems. Nietzsche insists that there is something genuinely mysterious about education at its best. He likes the language of mysticism: his chosen image for the true teacher is a mystagogue—a guide who initiates others into a mystery that cannot be fully explained. The most promising students are not just pupils, but initiates, admitted into a select circle of culture and insight. No wonder he never produced a detailed, realistic education plan. If the core of education belongs to mystery and genius, the idea of a carefully planned, scalable system already sounds like a betrayal.

A Philosophical Performance

Part of the impact of these lectures comes from the way Nietzsche stages them. Instead of simply preaching his views from the podium, he presents them through a fictional scene: an old philosopher and a former disciple walking in the forest and talking about education while “Nietzsche” and a friend happen to overhear them. He spends the entire first lecture just setting up this frame story.

The old philosopher becomes the mouthpiece for Nietzsche’s ideal of the true educator, and the dialogue format lets him dramatize tensions instead of simply stating conclusions. It is a theatrical way of doing philosophy, closer to ancient dialogues than to typical nineteenth-century university talks. In this form, Nietzsche is not only discussing education; he is performing his idea of what teaching should feel like—dramatic, unsettling, rooted in the authority of someone who stands above ordinary culture and speaks from a deeper tradition.

The Purpose of Education: Nurturing Genius

Behind all the drama, Nietzsche’s basic question is simple: what is education for?

His answer is uncompromising. Education exists to nurture natural talent and help rare geniuses reach their full potential. These individuals, he believes, are not created by schools or systems. Their origin is “metaphysical,” as if they come from somewhere beyond the ordinary flow of culture. But they need a rich cultural environment in which to ripen. Without this shelter, a genius either appears too early, fails to be understood, or simply withers.

In the lectures, the old philosopher explains that a true genius reflects the strengths and spirit of a people in a single person. He embodies that people’s highest purpose in his work, raises them above the trivial concerns of the moment, and links them to something lasting and eternal. For that to happen, the genius has to be nourished “in the lap of his people’s culture.” If that environment is missing or rotten, Nietzsche warns, the genius slips away “like a stranger driven forth from an uninhabitable country into wintery desolation.”

From this point of view, a state that wants to be great must be deeply concerned with cultivating its great individuals. Education, properly understood, is a greenhouse for those very few.

And Everyone Else?

Once you accept that picture, an uncomfortable question follows: what about all the others?

Nietzsche’s answer is where his elitism shows its most brutal side. If the purpose of education is to nurture genius, then those who lack the potential for genius should not be offered this kind of education at all. They can and must be trained to become doctors, engineers, lawyers, scientists and so on, but they should not consider themselves “educated” in the higher sense.

That category of “lesser ability” is huge. It includes not only the lazy and dull, but also the conscientious, the competent, the technically skilled. Nearly everyone, in Nietzsche’s scheme, falls short of the level at which true education makes sense.

He is not saying these people should remain ignorant. He accepts that a modern state needs professionals, and he does not object to their technical training. What he objects to is their self-image. For him, the catastrophe begins when they begin to see themselves as cultured, as members of an intellectual elite, as people whose opinions about great art, literature, philosophy and politics carry real weight.

More Stories

The “Smug Elite” of Mass Education

In Nietzsche’s Germany, plans were underway to expand education: more institutions, more access, more qualifications. For most reformers this was cause for celebration. For Nietzsche it was the sign of a cultural crisis.

His argument unfolds like this: once you decide to educate the masses, you need a huge number of teachers. But genuine educators—those rare figures with real depth and genius—are very few. The system cannot possibly fill all its positions with people of that caliber. It will inevitably turn to second-rate and third-rate minds.

These teachers, formed by a weak system, believe themselves to be well educated and capable. They then pass on that illusion to generation after generation of students. Each year, thousands leave school and university absolutely certain that they are cultured and enlightened. With their qualifications, they move into positions of influence and authority. From politics and administration to culture and media, they occupy the commanding heights of the state.

From Nietzsche’s perspective, the result is a disaster: the state is not led by great individuals but by what he calls a “shameless and smug elite.” These people have the badges of education but not the substance. They are full of self-confidence and opinions, but shallow in judgment. And because they believe deeply in their own education, they are almost impossible to correct.

Seen this way, mass education does not democratize culture; it floods it with competent mediocrity—and then persuades that mediocrity that it is the highest form of life.

Education Against Independent Judgement?

One of the most disturbing lines in these lectures comes when Nietzsche, again through his old philosopher, attacks the way teachers encourage students to express opinions on everything. He complains that teachers treat every student as if they were capable of literature and entitled to judgments on the most serious matters. True education, he insists, should “strive with all its might” to suppress this “ridiculous claim to independence of judgement,” and instead impose strict obedience to the sceptre of genius.

Read in isolation, that sentence sounds like a demand for submission and intellectual hierarchy taken to an extreme. Education, here, is not about forming free minds but about breaking down youthful confidence and training students to recognize and obey those rare figures who truly know.

Did Nietzsche actually mean this literally? Or is he pushing the point as far as it will go to shock his audience out of their complacency? Scholars are far from agreed, which is part of the reason Nietzsche keeps attracting readers from every political direction. His writing leaves room for interpretation; he forces you to decide what to take seriously and how far to follow him.

But whether we soften or stiffen this passage, its target is clear. Nietzsche thinks modern systems encourage students to overestimate their own understanding. Too many are sent out into the world with hot takes on everything and no real depth. His instinct is to turn the volume down on all that chatter and push them to confront the demands of something genuinely great.

How Should We Read Nietzsche Today?

Nietzsche was not naïve. He knew that his lectures would not prompt an overnight reversal of educational policy in Germany. His talk of mystagogues, initiates and metaphysical genius was never going to become the basis of a ministry of education blueprint. In that sense, his text is not a reform proposal. It is a provocation.

So what do we do with it now?

Most of us are not willing to follow him all the way. We don’t want a world where only a tiny elite can study literature or philosophy, and everyone else is told to accept their station and stop thinking for themselves. We value wider access, social mobility, and the idea that ordinary people can be educated in meaningful ways.

Yet Nietzsche’s critique still stings. When he warns about a culture where the word “educated” is inflated, where credentials substitute for depth, where confidence is confused with understanding, it is hard not to recognize something of our own world. His defence of true excellence—of the need for real greatness, not just competence and certificates—can make us uneasy precisely because it questions comfortable assumptions.

Perhaps the most productive way to read Anti-Education is not as a manual for how things should be, but as a mirror held up to how they are. He asks whether our schools and universities genuinely form deep minds or merely produce people who know how to pass through systems. He asks whether we can tell the difference between training and education, between being informed and being transformed.

We may reject his elitism. We may insist that independent judgement should be cultivated, not suppressed. But the questions he raises about shallow culture, inflated self-belief and the hollowness of a merely formal “education” are harder to dismiss. Nietzsche expected his readers to think for themselves, to argue back, and to find what is valuable in his ideas without blind obedience to his sceptre.

In that sense, ironically enough, engaging seriously with his attack on education may itself be one of the best educational exercises we could have.