When we picture the Ottoman dynasty, we usually imagine solemn sultans in silks, ruling with justice and piety. Officially, that was the ideal: rulers were expected to be devout, disciplined, and honorable.

In reality, some Ottoman sultans and princes were anything but.

Behind the ceremonial bowing and court rituals, there were drunken parties, opium habits, overstuffed harems, and princes who marched against their own fathers. The empire endured—but its royal family could be as chaotic as any soap opera.

Let’s step into the less flattering side of Ottoman court life.

Drinking Sultans: Wine in a “Dry” Empire

Islamic law, which formed part of the Ottoman legal system, forbade Muslims from drinking alcohol. Non-Muslims were allowed to drink, and in theory, Muslims were not. In practice, that “ban” was leaky—especially at the top.

Several Ottoman rulers openly enjoyed wine. Bayezid I (d. 1402) liked to host poetry gatherings where the verses flowed along with the wine. Mehmed II (d. 1476), the conqueror of Constantinople, was also rumored to enjoy a drink.

The real problem wasn’t just taste; it was excess.

Some princes went so far that their families panicked. Bayezid II heard that one of his sons had fallen deep into alcohol and opium, a situation his mother blamed on corrupt courtiers. For a dynasty that prided itself on discipline and good training, a drug-addicted prince wasn’t just embarrassing—it could undermine the sultan’s reputation as a father and ruler.

The most notorious drinker of all was Selim II (d. 1574), remembered by the nickname “Selim the Sot.” His father, Suleiman the Magnificent, had formally banned alcohol and imposed heavy fines on violators. Selim did the opposite: he allowed taverns to operate and alcohol to be sold more freely.

Selim’s end was darkly ironic. In 1574, reportedly drunk, he slipped on wet marble in the bath, hit his head, and died shortly after. For a man known for his love of wine, the setting felt tragically on brand.

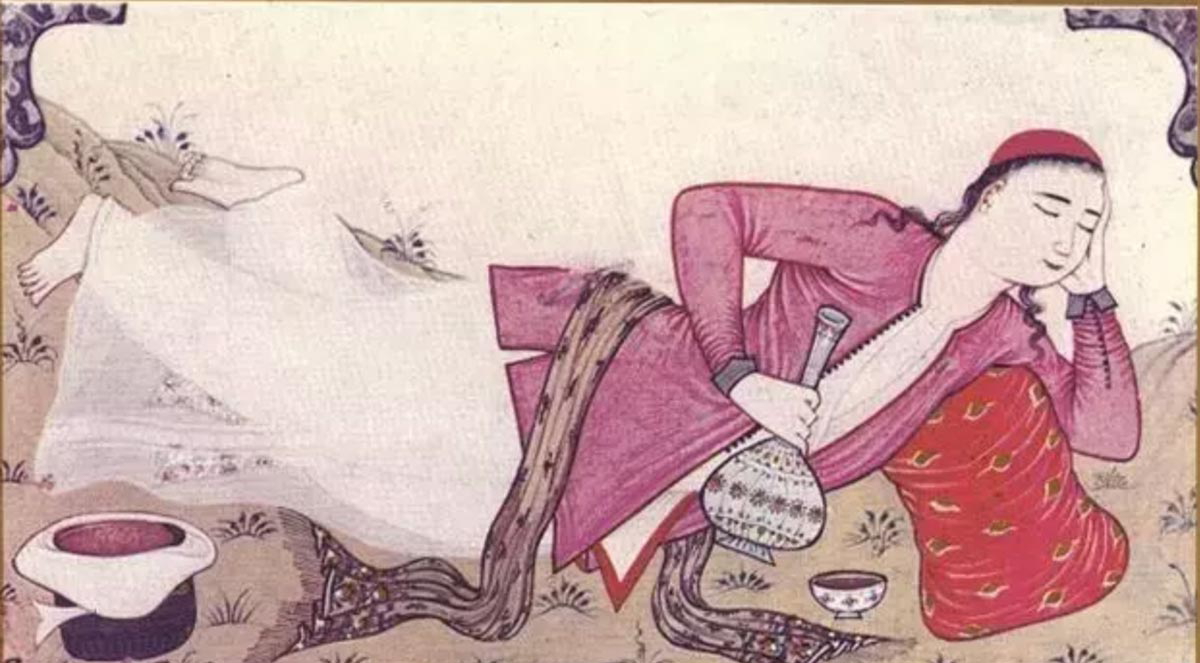

Opium and Hashish: High Princes, Harsh Crackdowns

Alcohol wasn’t the only substance in circulation. Like many societies before and after them, the Ottomans were familiar with psychoactive drugs.

The most common was afyon—opium. Poppy flowers grown in western Anatolia, especially around the city of Afyon (literally, “Opium”), supplied the raw material. Opium was widely used in premodern medicine: mixed into balms, salves, and potions for pain relief long before the isolation of morphine in the 19th century.

But it wasn’t only medicinal.

[block id=”auto-draft”]

Some members of the royal family used opium recreationally. Prince Bayezid II, for example, developed a strong addiction, which seriously damaged his relationship with his strict father, Mehmed II. For a future sultan, being known as an addict was more than a personal failing; it raised doubts about his fitness to rule.

Opium and hashish also fascinated writers. Sufi poetry, biographies, and medical texts all mentioned these substances—sometimes critically, sometimes simply as part of everyday life.

Yet once men like this reached the throne, many wanted to shake off any hint of vice.

Murad IV (d. 1640) is a classic case. As a young prince, some sources suggest he used opium himself. Later, as sultan, he became infamous for his harsh moral campaigns. He banned alcohol, tobacco, and opium, and personally patrolled the streets of Istanbul in disguise to catch offenders.

One story claims that when Murad discovered his chief physician, Emir Çelebi, carrying opium, he forced him to ingest the entire supply on the spot. Emir Çelebi fell into a coma and died that night. Whether embellished or not, the tale shows how far the sultan’s war on drugs was remembered as going—perhaps as much to erase his own past indulgence as to “clean up” the empire.

Women, the Harem, and Sultans Who Went Too Far

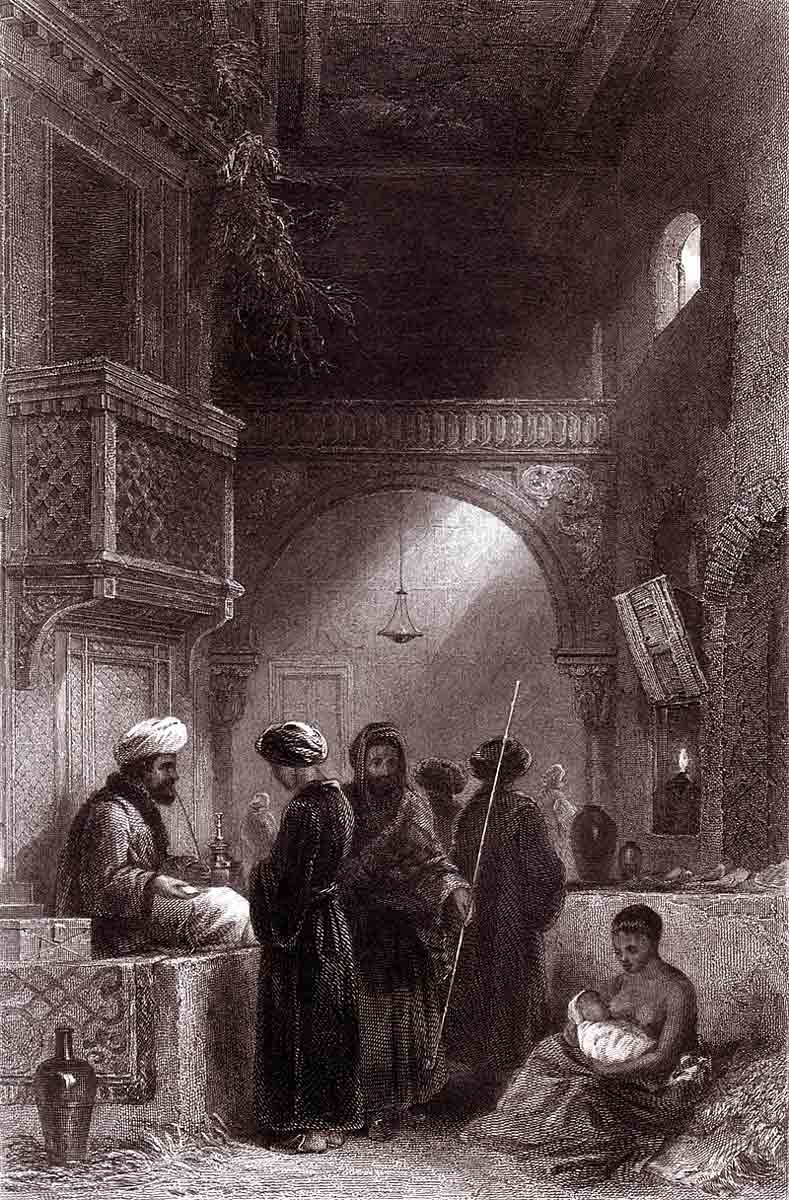

The Ottoman harem is often misunderstood. It was not just a “pleasure palace” but a complex domestic and political institution rooted in both Islamic and Byzantine traditions.

The harem was the women’s side of the palace: home to the sultan’s mother, wives, concubines, daughters, and female servants. Enslaved girls brought in from across the empire and beyond were trained in palace etiquette, music, embroidery, languages, and service. Most would spend their lives serving in the harem. A few—those who caught the sultan’s eye—became concubines or even legal wives.

Concubines lived at the mercy of the sultan. He could shower them with gifts, ignore them completely, exile them, or have them executed. But some climbed to extraordinary heights of power, eventually becoming queen mothers (valide sultans) who wielded enormous political influence.

At the same time, some sultans treated the harem like an endless buffet.

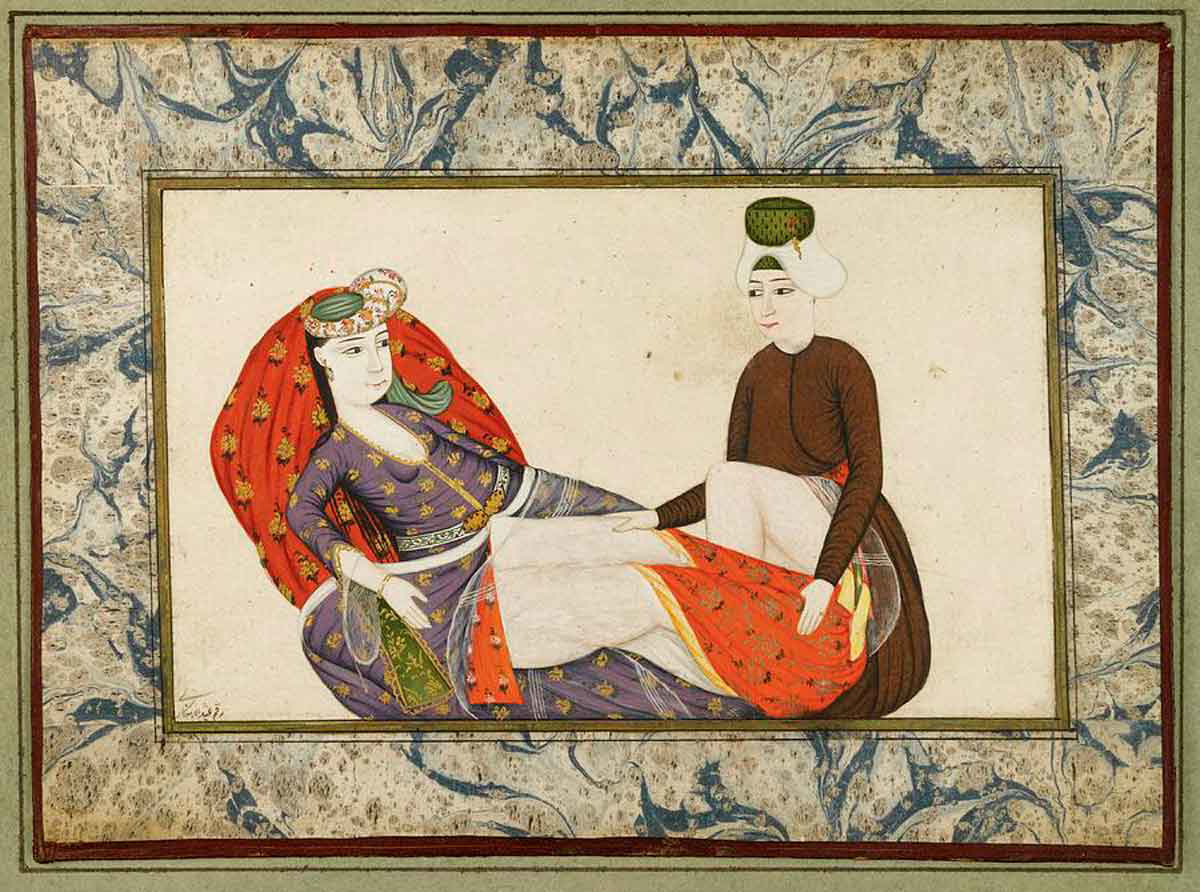

Murad III (d. 1595) is one of the most famous womanizers in Ottoman history. He is said to have fathered around 100 children. At first, he was devoted to a single concubine, Safiye Sultan, who would later become a powerful queen mother. Worried about Safiye’s influence, his mother and sister deliberately introduced other concubines to the harem to distract him.

It worked a little too well. By the time Murad died, seven of his concubines were pregnant. Concubines were normal in Ottoman courts, but Murad’s sheer number of partners and children shocked even contemporaries.

Then there was Ibrahim I (d. 1648), remembered as “Ibrahim the Mad.” He spent an enormous amount of time in the harem and had an unusual obsession: extremely obese women. He reportedly ordered his officials to find the fattest woman in Istanbul and bring her to him.

His desires could be politically explosive. When Ibrahim set his sights on Perihan Hanım, the wife of his grand vizier İpsir Mustafa Paşa, he ordered another statesman, Varvar Ali Paşa, to bring her to the capital. Varvar Ali was outraged—this was not just moral outrage, but political insult—and launched a rebellion. He was eventually defeated and executed, but Perihan Hanım was spared. Ibrahim’s behavior, however, fed the perception that he was unhinged and unfit to rule, contributing to his eventual downfall.

Princes Who Refused to Obey

If the private lives of sultans could be wild, the behavior of princes could be downright dangerous.

Succession in the Ottoman Empire did not follow the European rule of primogeniture. There was no automatic “eldest son gets the crown.” Instead, every male member of the royal family had a theoretical claim. The throne usually went to whoever could gather the most support from key figures like viziers and the Janissaries and then defeat his rivals—often his own brothers.

This system, with roots in earlier Turkic and Mongol practices, almost guaranteed tension between generations.

Princes were often sent out as provincial governors, given troops and responsibilities far from the capital. That meant they had power bases of their own—and occasionally, they used them.

In the 1370s, one such prince, Savcı Bey, son of Sultan Murad I, decided he had waited long enough. He teamed up with Byzantine prince Andronikos, who was similarly plotting against his own father. The two planned a joint revolt to overthrow both rulers.

Their fathers found out.

The punishment was brutal. Both young men were blinded, stripping them of the physical wholeness expected of a sovereign and destroying their political support. Murad later had Savcı Bey executed. The message to other princes was clear: rebellion could cost you more than your crown.

Not all rebellious princes failed.

Selim, later known as Selim the Grim, repeatedly disobeyed his father, Sultan Bayezid II. He believed Bayezid was too soft toward their Persian rivals, the Safavids. Acting on his own initiative, Selim marched east, defeated Safavid forces, and secured the frontier.

These victories won him the loyalty of the Janissaries, the elite infantry who were kingmakers in Ottoman politics. With their backing, Selim forced his father to abdicate in 1512 and took the throne himself. His ruthlessness didn’t stop at his father—he later had many of his own relatives killed to eliminate future rivals.

[block id=”related”]

Power, Pressure, and the Human Side of the Ottoman Court

Stories of drunken sultans, opium-using princes, harem scandals, and rebellious heirs can sound like colorful gossip from a distant past. But they also reveal deeper truths about life at the top of the Ottoman Empire.

These rulers and princes were expected to embody the highest ideals of their civilization: piety, justice, self-control, and strength. They lived under immense pressure, surrounded by flattery, wealth, and constant danger from rivals. In that environment, indulgence and self-destruction were never far away.

Some sultans leaned into vice and paid for it with their lives or reputations. Others tried to stamp out the very habits they themselves had practiced in their youth. Princes gambled everything—including their eyes, their honor, and their lives—on ambition.

Behind the titles and the turbans, the Ottoman royal family was made up of deeply human figures: flawed, impulsive, brilliant, reckless. Their vices didn’t bring down the empire on their own—but they shaped its politics, its court intrigues, and its history in ways we’re still uncovering today.