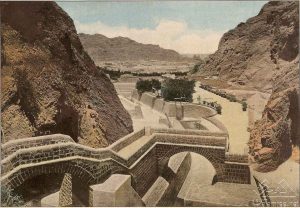

Petra sits 900 m above sea level in the rugged Sharra Mountains of southern Jordan, cupped by sheer sandstone cliffs whose only breach is the narrow, twisting Siq. UNESCO calls it “one of the most precious cultural properties of man’s cultural heritage,” and with reason: between c. 300 BC and AD 100 the Nabataeans funnelled nearly every grain of frankincense and myrrh that perfumed Mediterranean temples through this hidden valley.

Contemporary writers from Strabo to Pliny the Elder marvelled that a people with no navy, small armies, and no farmland could nonetheless “dictate prices to Syria and Egypt.” What they possessed, however, were camels, water, and trust—three currencies strong enough to knit Arabia, India, and Rome into a single scented economy.

🐪 Nomads Become Middle-Men: The Rise of the Nabataeans

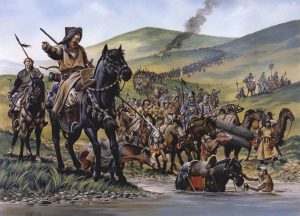

Long before chisels rang in Petra’s gorges, small Bedouin clans wandered seasonal grazing grounds between the Hejaz and the Negev. Greek sources first notice them in 312 BC, when Antigonus I dispatched an army to seize their “spice treasure”—and lost it to a swift camel-mounted counterattack. Those clans soon coalesced, perhaps absorbing Edomite and Aramaean neighbours, into a loose confederation led by elected shaykhs.

Their genius lay in monopolising water holes on the north–south caravan corridor: whoever drank, paid. By the reign of King Obodas I (c. 90 BC) the Nabataeans could field war-camel corps, strike their own silver drachms, and hire Greek architects for their rock-cut tombs. Crucially, they developed a stable cursive script—Nabataeo-Aramaic—that standardised trade contracts even when buyers wrote in Greek or Demotic Egyptian.

🏗️ Carving a Fortress-Marketplace

Petra’s spectacular façades often distract from its real marvel: the hydraulic infrastructure hidden behind the stone masks. Beginning in the third century BC Nabataean masons:

- Tamed floods by building 90-m dams across Wadi Musa. A 2023 hydrological study estimates their barrier system could divert 300 000 m³ of flash-water in a single storm.

- Drilled channels 1 ½ km through the Siq’s left wall, sheathing the conduit in waterproof hydraulic plaster still intact in spots.

- Excavated cisterns hacked deep into bedrock and roofed to prevent evaporation; modern laser scans count over 650 such tanks across the valley.

These measures yielded an annual storage approaching 40 million litres—enough to fill Olympic pools weekly and support orchards of pomegranates and vines that stunned travellers expecting a desert outpost. The surplus sponsored monumental projects: the 8 500-seat Theatre, the free-standing Qasr al-Bint temple, and dozens of mausoleums whose façades fuse Hellenistic tholoi, Egyptian cornices, and local step-motifs.

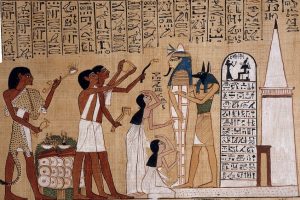

🌿 Frankincense & Myrrh

Frankincense exudes as milky sap from Boswellia sacra trees clinging to the limestone escarpments of Dhofar and Hadhramaut; myrrh seeps from Commiphora myrrha in thorny groves further inland. Harvesters gashed bark with a mengaffal knife, returning weeks later for crystallised “tears.” Each mature tree produced barely 3 kg a season. Roman demand was voracious: Pliny prices the finest frankincense at six denarii per Roman pound (c. 327 g) in his Natural History—roughly a week’s wages for a legionary.

Beyond incense burners, these resins flavoured wine, disinfected wounds, treated digestive ailments, and—mixed with honey—served as aphrodisiacs recommended by Dioscorides. Jewish liturgy burned frankincense on the Temple altar; early Christian congregations debated but soon adopted the practice. Every pinch cast into a brazier in Rome began its journey on camel-back through Nabataean checkpoints.

🐫 Across the Dunes: How Incense Moved

A standard caravan left the incense ports of Shabwah or Aden with 1 500–2 000 camels, each carrying c. 200 kg in woven panniers. Caravans advanced 25–30 km per day, guided at night by astral navigation and by day via cairns. Nabataean entrepreneurs invested heavily in:

- Desert stations (khan): fortified rest-houses every 30 km supplied with water-skins and barley.

- Tax outposts: rock shelters where clerks stamped clay sealings onto incense sacks—an anti-tamper guarantee for buyers in Gaza or Damascus.

- Wadi Arabah road crews: labourers cleared boulders and smoothed gradients so heavily laden camels could maintain pace.

From Petra, caravans split along three arteries: northward on the King’s Highway, westward to Gaza’s seaport, and south-west to Leuce Come on the Red Sea, where Nabataean skippers transferred cargo to Alexandrian brokers. (Trade on the Red Sea – Nabataea.net, Incense trade route – Wikipedia)

Image 3—Map of the Incense Route

Caption: “From Dhofar to the Forum: 2 000 km of dust and profit.”

🏛️ Petra: Customs-House of the Aromatic World

Within Petra’s colonnaded market, merchants operated under regulations carved on limestone stelae:

- Duties ranged from 5–10 % payable in silver, gold, or spices—whichever the royal treasurer preferred.

- Weights & measures used bronze steelyards calibrated in Minae; inspectors wielded chisels to confiscate falsified scale pans.

- Coinage: bronze and silver issues of Aretas IV depict twin cornucopias—propaganda for abundance—and circulated alongside Roman denarii.

The Market Plaza itself hosted warehouses with plastered floors to keep resin bags dry, while a marble “Spice Deity” statue—perhaps Al-Uzza—received token handfuls of frankincense from every outgoing shipment, blending finance with piety. Contemporary ostraca list women such as Hulmu and Yadʿu signing as guarantors, showing that elite Nabataean women controlled caravans and credit lines.

⚖️ Balancing Empires, Guarding Profits

Geopolitics was as perilous as sandstorms. Nabataea:

- Supplied war elephants to the Hasmoneans but simultaneously sold cereal surpluses to Ptolemaic Egypt.

- Appears in the New Testament: Aretas IV’s governor tries to arrest St Paul in Damascus (2 Cor 11:32).

- Maintained uneasy coexistence with Herod the Great—Herod married a Nabataean princess, then divorced her, triggering border war.

Diplomacy bought time, but profit tempted Rome. In AD 106, Emperor Trajan annexed the kingdom, paving the Via Nova Traiana (430 km) to Bosra. Yet the province of Arabia Petraea retained many former officials, suggesting Rome preferred cooperative integration over outright suppression.

🎭 Gods, Aromas, and Everyday Life

Religion permeated commerce. High on Jabal al-Madbah priests burnt resin on limestone altars, the scent believed to bridge mortal and celestial realms. Recent 2022 excavations uncovered tiny ceramic incense spoons and a rhyton dedicated to Dushara, Petra’s cubic high-god, confirming textual hints that even mountain summits functioned as open-air temples.

Daily life blended cultures: musicians in the Theatre played double auloi; Greek inscriptions honour benefactor Alexandros the Wine-Merchant; yet household shrines show betyls—aniconic sacred stones—echoing Arabia. Gardens of fig, olive, and oleander shaded peristyle courtyards, irrigated by terracotta pipes fed from the Siq channel.

🚚 Trafficking Tricks and Tariffs

The Roman state imposed a spine-tingling 25 % import tax on luxuries at Alexandria. To preserve margins, Nabataean brokers:

- Re-routed cargos through minor Red Sea inlets, then overland to bypass the Alexandrian customs house.

- Re-labelled amphorae, firing counterfeit producer stamps to disguise Yemeni origins as Egyptian—exploiting lower domestic tariff codes.

- Staggered convoys so that scarcity inflated prices in Rome during festival seasons (Saturnalia, Parentalia).

Papyrus archives from Oxyrhynchus complain that incense availability “rose and fell with the whims of Arab camel masters,” a grudging acknowledgement of Nabataean market power.

🌊 Decline on Shifting Sands

Three tectonic shifts eroded Petra’s monopoly:

- Sea Change: By the late 1st century BC Greek navigator Hippalus mapped monsoon winds, allowing Roman ships to sail directly from Red Sea ports to India. Ocean freight cost one-third the caravan rate per kilogram.

- Palmyrene Competition: In AD 260 Palmyra’s king Odaenathus captured key oases, diverting north-bound trade onto Euphrates routes.

- Natural Disaster: An AD 363 earthquake sheared water conduits and collapsed façades; surveys find sediment infill layers 2 m deep sealing cistern mouths. Population likely fell below 5 000 within decades.

🛠️ Unearthing the Scent of History

Modern science continues to peel back sand-buried chapters:

- 2021 drone-LiDAR mapped a monumental platform north of the city—possibly a caravanserai able to stable 300 camels.

- 2024 excavation beneath Al-Khazneh uncovered a vaulted crypt with six resin-encrusted bronze censers and a silver chalice; residue analysis identified both frankincense and the rarer bdellium.

- Hydrological engineers re-opened a Nabataean dam in 2023, proving it can still handle a 50-year flood event after minor repairs.

🧭 Legacy of a Perfumed Empire

Petra’s story reminds us that ideas, not armies, often win deserts. By mastering water, trust, and information, the Nabataeans built an economic empire whose reach stretched from Indian spice farms to Roman basilicas—and they did so without conquering a single province. Their carved façades endure as a ledger written in sandstone, testifying that a handful of aromatic tears, carefully shepherded, could bankroll theatres, irrigate gardens, and bend emperors to negotiation.

Stand today in the Siq’s cool shadows, breathe crisp desert air, and imagine the ghost-scent of frankincense drifting above camel bells: echoes of a kingdom that traded fragrance for immortality.