“Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

Lord Acton had medieval popes very much in mind when he wrote that, and few figures prove his point better than Pope John XII—the teenage pontiff whose short, scandal-filled reign in the 10th century reads like a warning label on unchecked power.

Some popes were saints. Some were shrewd politicians. John XII? He became a symbol of everything the Church wishes had never happened.

From Persecuted Church to Power Player

By the time John XII arrived on the scene, the Catholic Church had traveled a long way from its early days of persecution under the Roman Empire.

In the year 800, Pope Leo III had placed a crown on Charlemagne’s head and proclaimed him Emperor. That moment symbolized the new reality: the papacy was no longer just a spiritual authority—it was a central player in European politics.

As the Western world fractured and kingdoms rose and fell, the Vatican became a rare constant. That stability made it incredibly attractive to powerful Italian families who wanted control over Rome—and over the pope.

Rich nobles began treating Church offices like prizes. They:

- schemed and bribed

- installed relatives as bishops

- maneuvered to place their own men on the papal throne

Holiness was optional. Connections were essential.

The “Rule of Harlots”: Rome’s Dark Age

This constant meddling produced one of the most infamous stretches in papal history. The 10th century papacy has been nicknamed:

- “The Pornocracy”

- “The Rule of Harlots”

- “Saeculum Obscurum” – “the Dark Age”

Popes came and went as puppets of powerful Roman clans. Many were immoral, some were violent, and most were more politician than pastor.

A few lowlights from this era:

- Pope Sergius III may have fathered an illegitimate son who later became pope (John XI).

- Pope John X allegedly used romantic relationships with powerful women to climb into the papal office—and may have been murdered by one of them when he outlived his usefulness.

- Pope Stephen VII was mocked simply for going clean-shaven, which sounds trivial—until you realize how obsessed the medieval Church could be with outward signs and customs.

And yet, as bad as all this was, it was only the prelude.

Because then came John XII.

Octavianus: The Teenager Forced onto Peter’s Throne

John XII was born Octavianus in the 930s, into one of Italy’s most influential families. His father, Alberic II of Rome, was a ruthless power broker who controlled the city with an iron fist.

Alberic had already seized power by throwing his own mother and stepfather into prison. To secure his legacy, he went one step further: he forced the Roman nobility and clergy to swear that when the current pope died, they would elect his son Octavianus as the next pope.

This was blatantly illegal and deeply uncanonical—but it worked.

In 955, when he was about 18 years old, Octavianus became Pope John XII, the 130th Bishop of Rome and the youngest pope in history.

What followed made the earlier corruption look almost polite.

The Wicked Life of John XII

From the very start, John XII seemed far more interested in pleasure and power than in prayer or reform.

Our main sources about his reign are not entirely neutral—they come from his enemies and later chroniclers—but even with exaggeration discounted, a consistent picture emerges: a pope with shockingly lax morals.

Accusations against him include:

- Skipping his duties to go hunting

- Maintaining multiple mistresses

- Drinking heavily and partying

- Selling church offices for cash (simony)

- Giving church lands to his lover

- Gambling with Church wealth and allegedly calling on pagan gods and the devil as he did so

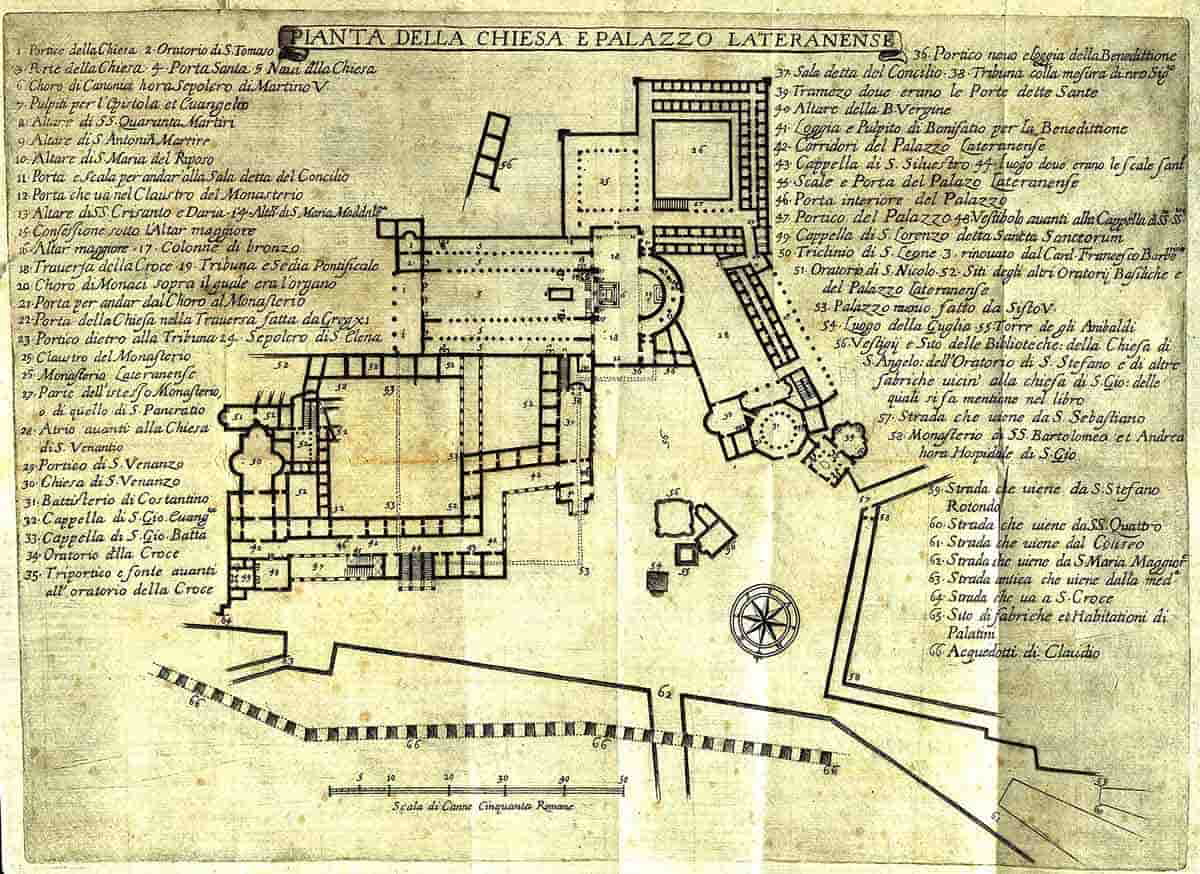

- Turning the Lateran Palace—the original papal residence—into something like a brothel, with prostitutes supposedly roaming the halls

Some of these charges were probably inflated for political effect. But there’s little doubt that John XII lived more like a feudal playboy than the spiritual leader of Western Christendom.

Even so, it wasn’t his moral failures that finally brought him down. It was his terrible judgment in politics and war.

A Would-Be Warrior Pope

By John XII’s time, the Church held lands in central Italy known as the “Patrimony of Peter.” These had once been guaranteed by Charlemagne to support the Church’s work, but over the centuries, other lords and local rulers had chipped away at them.

John decided he would restore papal power by force.

The result was a disaster.

- His campaign against the Lombards failed miserably.

- His attempt to fight Berengar II, King of Italy, overstretched his forces and ended in humiliating defeat.

By 960, Berengar’s forces were pillaging papal lands, and the prestige of John XII was in ruins. The Roman nobles were furious. The pope had failed both as a moral leader and as a military one.

He needed a savior—and he found one in Otto of Saxony.

Otto the Great and the Ottonian Privilege

Otto I, King of East Francia (roughly modern Germany), had his own reasons to hate Berengar II. Otto had married the widow of the previous king of Italy, and Berengar’s rule was a personal and political insult.

So when John XII invited Otto to Italy and dangled an extraordinary prize—the imperial crown—Otto answered.

By 961, Otto had defeated Berengar and was poised as the most powerful ruler in the region. In Rome, John XII crowned him Holy Roman Emperor, promising eternal friendship and alliance.

But there was a catch.

In return, Otto issued the Ottonian Privilege, which declared that future popes would have to swear loyalty to the Holy Roman Emperor. It was a formal invitation for imperial interference in papal elections and Church affairs.

For a pope drunk on his own status as “God’s representative on earth,” this was intolerable. John XII wanted Otto’s sword, not his shadow. His betrayal began almost immediately.

Betrayal, Trial, and Exile

As soon as Otto left Rome to finish dealing with Berengar, John XII started secretly seeking new allies against the man who had just saved his position.

He sent letters to:

- The Byzantine Empire

- The Hungarians

- And even Berengar II himself

It was a staggering act of political stupidity—made worse by the fact that Otto’s men intercepted the messengers.

Enraged, Otto marched back to Rome in 963.

John XII tried to resist. He donned armor, led what forces he could muster, and reportedly managed to push Otto’s army back across the Tiber at one point. But it was hopeless. The emperor’s power was overwhelming, and the people of Rome were tired of the pope’s scandals and failures.

John XII fled Rome, taking the papal treasury with him.

Otto entered the city and demanded that John return to face charges. When the pope refused, Otto convened a synod and tried him in absentia.

The charges compiled at this council—ranging from murder to perjury to sacrilege—paint a picture so lurid that historians rightly treat them with caution. But they also reveal just how far John’s reputation had fallen.

The bishops of Rome, under pressure from Otto and disgusted by John, agreed to depose him and elected a new pope: Leo VIII—a layman elevated rapidly to the highest office.

With that, Otto believed the problem solved. He left Rome.

That was his mistake.

John Strikes Back

Leo VIII’s authority rested almost entirely on Otto’s army. Once the emperor withdrew, his support in Rome disintegrated.

John XII, watching from exile, saw his chance.

He called on his remaining allies and orchestrated a rebellion. The uprising succeeded in driving Leo VIII out of the city and restoring John XII to the papal throne.

If anyone hoped that exile had humbled him, they were quickly disappointed.

Upon returning, John XII unleashed a wave of brutal reprisals:

- Bishops who had supported Leo were scourged

- Some reportedly had their tongues cut out

- Others had limbs hacked off

Far from a chastened penitent, John returned as a vindictive ruler eager to punish anyone who had crossed him.

A Scandalous Death

His second reign didn’t last long.

In 964, at around the age of 28, John XII died suddenly. The exact circumstances are murky, but the stories—like everything about him—are dramatic.

Two rival accounts emerged:

- In one version, he suffered a stroke while committing adultery with a married woman.

- In another, the woman’s enraged husband caught them in bed and threw the pope out of a window, killing him.

We’re unlikely ever to know the truth. But the fact that both stories place him in a compromising situation with another man’s wife fits the way his contemporaries—and later generations—chose to remember him.

With his death, one of the most notorious papal careers in history came to an abrupt end.

John XII’s Lasting Damage

Were all the accusations against John XII true? Almost certainly not. Many were shaped, sharpened, or outright fabricated by his enemies—political and imperial—who needed to justify deposing a pope.

But even if half the stories are exaggerations, enough remains to show a deeply flawed leader whose personal vices and political blunders had real consequences.

His legacy includes:

- Staining the reputation of the papacy for generations

- Normalizing imperial interference in papal elections through the Ottonian Privilege

- Deepening the tension between spiritual and secular power in the Latin West

It took nearly a century of reform efforts—including movements like the Gregorian Reform—before the Church gradually clawed its way out of the shadows cast by men like John XII and the corrupt age that produced him.

Lord Acton’s quote about power and corruption is often repeated as a cliché. But look at the story of Pope John XII—a teenager handed supreme spiritual and political authority with no limits, no accountability, and no check on his appetites—and it stops being a cliché.

It becomes a case study.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Crazy Soup: How Early Colonial Mexico Became the World’s First Global City

Discover Michigan’s Historic Towns: The Top 10 Addresses

How to Read the 6 Jane Austen Novels

What Is the Philosophy of Film?

The Nazi-Soviet Pact: A Deal with the Devil

The Hollow Earth: From Halley to UFOs

The Epic Rise and Tragic Fall of Julius Caesar

War of 1812: Winners, Losers, and Lasting Effects

Imperial Cult: When Roman Emperors Canonized

Aelfgifu: Queen of England and Denmark

The Russian Apartment Bombings of 1999: Unraveling the Mystery

Egyptian Art: From Balance to Brilliance