The 1850s were largely indifferent to parliamentary reform in Britain. But from 1859–60, a reform current gathered that would culminate in the Second Reform Act of 1867. Domestic forces mattered—the spread of trade unionism, the rise of articulate union leaders, and the growth of middle-class radicalism under John Bright. Even more decisive were foreign crises that electrified public opinion: Italy’s war in 1859, the Polish Revolt of 1863, and, above all, the American Civil War (1861–65). To many British workers, Abraham Lincoln and the Union seemed to be fighting for democracy; to critics at home, the Union represented exactly the kind of “rampant” democracy Britain should fear.

This global turbulence helped forge an informal alliance between trade unionists and Bright’s middle-class radicals—symbolized by two joint mass meetings in 1863 supporting Polish insurgents and the American North—and received a further boost from Giuseppe Garibaldi’s celebrated 1864 visit to England. Out of this momentum came the Reform League in 1865, the era’s most powerful working-class pressure group and the only major organization to demand full manhood suffrage.

On May 11, 1865—one day after the League’s formation—William Ewart Gladstone made his famous claim that every man not disqualified by “unfitness” or “political danger” was “morally entitled to come within the pale of the constitution.”

From Palmerston’s Veto to Disraeli’s Bill

The main obstacle was Prime Minister Lord Palmerston’s hostility to reform. His death on October 18, 1865, broke the logjam. Lord John Russell became Whig premier, Gladstone led the Commons, and in March 1866 the government introduced a cautious bill to enfranchise £7 householders and some lodgers in boroughs and £14 occupiers in counties, with redistribution postponed.

This modest measure detonated a much larger argument about “democracy.” Conservatives, led intellectually by Lord Robert Cecil (the future Marquess of Salisbury), warned that even a £7 borough franchise would start a “revolution taken by inches,” ending in universal suffrage. Democracy, Cecil argued, would bring “absolute and unrestrained” rule by the many poor over the few rich, with little real benefit for workers and grave risks to property and the constitution.

The anti-democratic critique was not confined to Tories. Thomas Carlyle’s “Shooting Niagara—and After?” ridiculed manhood suffrage as a quack cure-all—merely importing new “supplies of block-headism” into Parliament. The Economist voiced a liberal-intelligentsia anxiety that “mind” (capital, expertise, culture) would be swamped by “mere numbers.”

No parliamentary critic pressed the case harder than Robert Lowe, a Liberal and former education minister. Between 1866 and 1867 he delivered the House of Commons’ most comprehensive nineteenth-century case against democracy. Reform, he said, must be justified by consequences, not abstract principle: had the working classes truly suffered without the vote, given three decades of worker-friendly legislation since 1832? Lowering the borough threshold would not stop at £7; tampering with the franchise would set Britain “adrift on the ocean of Democracy without chart or compass.” Democracy would empower class legislation, embolden trade unions, weaken executive authority, and aggravate corruption.

Paradoxically, Lowe’s sweeping rhetoric alienated potential allies. Queen Victoria retorted that the working classes were “the best people in the country”; Disraeli personally disliked Lowe; and the breakaway Liberal “Adullamites” never fused with the Conservatives. Still, a Tory–Adullamite combination defeated the Russell–Gladstone bill on June 18, 1866, toppling the government and bringing in a minority Conservative ministry under Lord Derby with Benjamin Disraeli leading the Commons.

Hyde Park and the Conservative Conversion

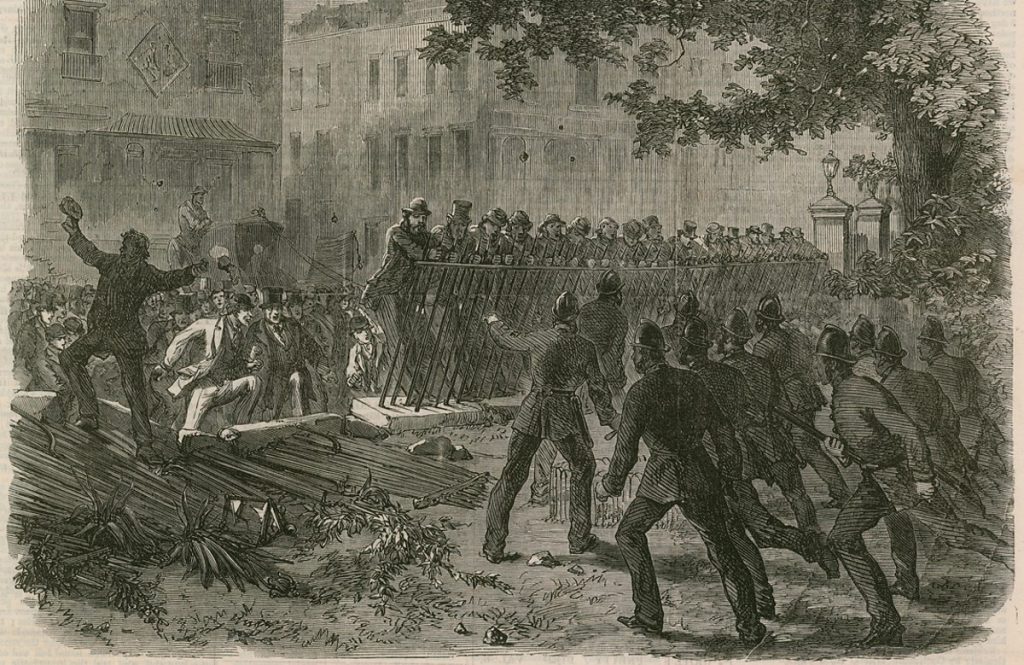

The Reform League revived with vast meetings and processions. Tensions peaked in the Hyde Park Affair of July 23, 1866, when police barred a League procession; crowds broke down the railings and occupied the park for three days. Disraeli was unsettled but unconvinced that reform had become a truly popular imperative. Lord Derby, prodded by public pressure and the Queen’s desire for settlement, gradually concluded the government would have to act. By late February 1867, Derby and Disraeli accepted a household-suffrage bill—initially hedged with “safeguards.”

Under relentless Liberal pressure, those safeguards dissolved. The government’s failure to block a huge Reform League meeting in Hyde Park on May 6, 1867, was hailed by League leader Edmond Beales as “a great moral triumph.” Within weeks, Disraeli accepted Hodgkinson’s Amendment abolishing the distinction between compound householders and personal ratepayers in boroughs—quadrupling the intended additions to the register. Thus, a Conservative government carried a far more sweeping franchise measure than the Liberals’ defeated bill of 1866.

What the Act Changed—and What It Didn’t

Contemporaries on both Left and Right proclaimed a democratic watershed. Nearly a million new voters were added, and in the large towns the working classes formed clear majorities. Radicals hailed “the first stage in the New Revolution.” Cecil lamented that Parliament’s “omnipotence” had passed to those with “no property but the labour of their hands,” and that constitutional “equilibrium” had been shaken by governing elites who had lost the will to fight.

Yet a circle of liberal observers—Frederic Harrison, Leslie Stephen, and especially the radical lawyer Bernard Cracroft—argued that social realities would blunt the Act’s democratic edge. Cracroft distinguished between direct and indirect representation. By kinship, patronage, education, and prestige—“one vast cousinhood”—the aristocracy and landed interest permeated the Commons. These ties, he suggested, would continue to shape outcomes regardless of the extended franchise: the questions politicians pursued would broaden, but the class wielding real influence would change slowly.

Subsequent research has largely borne out this emphasis on continuity. The Act transformed the big boroughs but left the counties relatively untouched. County electors increased by only about 40% (from c. 540,000 to 790,000), and rural areas remained over-weighted compared to small towns and mining villages, preserving Conservative strongholds. Redistribution was modest (just 53 seats), leaving many anomalies intact; more than 70 boroughs still had populations under 10,000 after 1867. Despite the 1872 secret ballot, corruption, bribery, and deferential voting habits persisted.

Accordingly, the Commons’ social profile changed gradually. In 1880 there were still 155 MPs related to the peerage (165 in 1865) and only 112 representing manufacturing (90 in 1865). Lawyers and military men remained numerous. The true “break,” some historians argue, came not in 1867 but in 1880–86, driven as much by economics as by politics. Mid-Victorian prosperity sustained the old hierarchical order even as it fostered confidence for reform. It also nourished a new conservatism among suburban middle classes—prosperous, self-conscious, wary of working-class radicalism—who increasingly favored the Conservatives.

Elections, Suburbs, and Conservative Ascendancy

The first post-Act election (1868) contained two telling signs. No working man entered Parliament, and two traditionally radical seats—Westminster and Middlesex—went Conservative. John Stuart Mill lost Westminster to bookseller W. H. Smith. In Middlesex, a young Guards officer, Lord George Hamilton, credited suburbanization for his victory: the spread of railways and the exodus of professionals and clerks to the outskirts had changed the constituency’s political tone.

These trends helped deliver the Conservatives’ 1874 triumph. Of thirteen working-class candidates, only two won—and both with Liberal backing. As Frederic Harrison observed, the Conservatives had become as much the middle-class party as the Liberals had been; “sleek citizens” commuting from “snug villas” found reassurance in Conservative stability.

From 1874 through the century’s end, Conservative dominance was pronounced—especially given the uneven achievements of Gladstone’s later ministries. And the symbol of this continuity was the premiership of the very man who had once thundered against democratic doom: the third Marquess of Salisbury, formerly Lord Robert Cecil.

Conclusion

The Second Reform Act did not inaugurate an era of immediate working-class rule. It did, however, restructure the relationship between electorate and government, democratizing large towns while leaving county politics and parliamentary composition largely intact. The Act’s most enduring legacy lay less in a sudden transfer of power than in the recalibration of political incentives: parties, courting a broader electorate, increasingly addressed social questions they had once ignored. In short, 1867 opened the democratic door—but the pace and path of those who walked through it were set by deeper continuities of class, economy, and political culture.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Livia Augusta—First Roman Empress

Ancient Greek Warfare Tactics Explained

The Largest Urban Centers in Medieval Times

The Tragic Wisdom of Croesus in Herodotus’ Histories

5 Uncanny Coincidences in U.S. History

Understanding Blitzkrieg Tactics: Lightning War Unleashed

Inside a Japanese Castle

How the Medieval Church Shaped Everyday Life in Europe

Julius Caesar and the Danger of Punishment Without Due Process

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

The Life and Reign of Saint-King Louis IX of France

Roman Voyages to Indo-Parthian India