Short version: Sir Thomas More was a brilliant lawyer, writer, and statesman who rose to the top of King Henry VIII’s court—but he would not accept the king as head of the Church. He refused the royal oaths, was tried for treason, and was executed in 1535. His courage made him a Catholic martyr. His book Utopia made him famous across Europe. His choices—and his clash with Henry—made him deeply controversial.

From London Schoolboy to Star Scholar

Thomas More was born on February 7, 1478, on Milk Street in London. His father, Sir John More, was a successful lawyer; his mother was Agnes. Thomas was the second of six children.

He studied at St Anthony’s School, one of London’s best. As a teenager, he served as a page in the household of John Morton, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Morton encouraged the “New Learning”—what we now call humanism—and pushed the talented boy toward university.

In 1492, More went to Oxford. He learned Latin and Greek and gained a strong classical education. But his father wanted him to be a lawyer, so after two years he left Oxford to study law at Lincoln’s Inn. He was called to the Bar in 1502.

A Bold Young Politician

More’s political life began soon after he qualified as a lawyer. In 1504, he entered Parliament representing Great Yarmouth. He quickly showed he was not afraid to speak against the crown when he thought it was right. That year he helped cut King Henry VII’s demand for money. The king punished him indirectly by imprisoning More’s father until the family paid a fine. More stepped back from public life for a time.

By 1510, he returned as one of London’s undersheriffs—an important city post. In 1514, he became Master of Requests and then a Privy Councillor, rising inside the royal court. He served on diplomatic missions, including to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and attended the grand “Field of the Cloth of Gold” in 1520 with Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and King Henry VIII. In 1521, he was knighted and made under-treasurer of the Exchequer. His career was clearly on the way up.

Henry VIII’s Trusted Courtier

Now Sir Thomas More, he became a key figure who could talk to both the king and Wolsey, whose relationship was getting tense. In 1525, Wolsey nominated More to be Speaker of the House of Commons. More’s skill, calm manner, and clear mind made him stand out. He was respected across the court and known for hard work and integrity.

The Peak: Lord Chancellor of England

In 1529, Wolsey fell from power. Henry VIII wanted a new Lord Chancellor—someone he trusted. He chose Sir Thomas More.

But the biggest storm of the age was breaking. Henry wanted his marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled. The pope would not grant it. Across Europe, new religious ideas from Martin Luther and others were spreading. In England, the king began moving toward a break with Rome. Parliament became the tool to make it happen.

The Reformation Parliament—and a Line in the Sand

Henry declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England. This was the core of the English Reformation. More, a loyal Catholic, believed the pope held spiritual authority as St. Peter’s successor. The king, to him, was a secular ruler—not head of the Church.

In 1530, More refused to sign a letter asking Pope Clement VII to annul Henry’s marriage. Soon after, the crown demanded that clergy acknowledge Henry as the Church’s head—the Oath of Supremacy. Many submitted. More did not.

He tried to avoid making a public scene. On May 16, 1532, he resigned as Lord Chancellor. He hoped private silence would protect both his conscience and his safety.

Pressure Mounts: The Oaths and the Accusations

Henry planned to marry Anne Boleyn. More was invited to the wedding in 1533 but declined. This angered the king. Charges followed—heresy and bribery—though they did not stick.

In 1534, Thomas Cromwell, the king’s chief minister, accused More of advising a nun, Elizabeth Barton, who prophesied doom for Henry because of the divorce. Those charges were dropped. But soon came the Act of Succession: it required a new oath that recognized Anne Boleyn as queen and her children as heirs. More refused again.

By now, the matter was clear. More would not bend on the Church or the succession. He was arrested and sent to the Tower of London for treason.

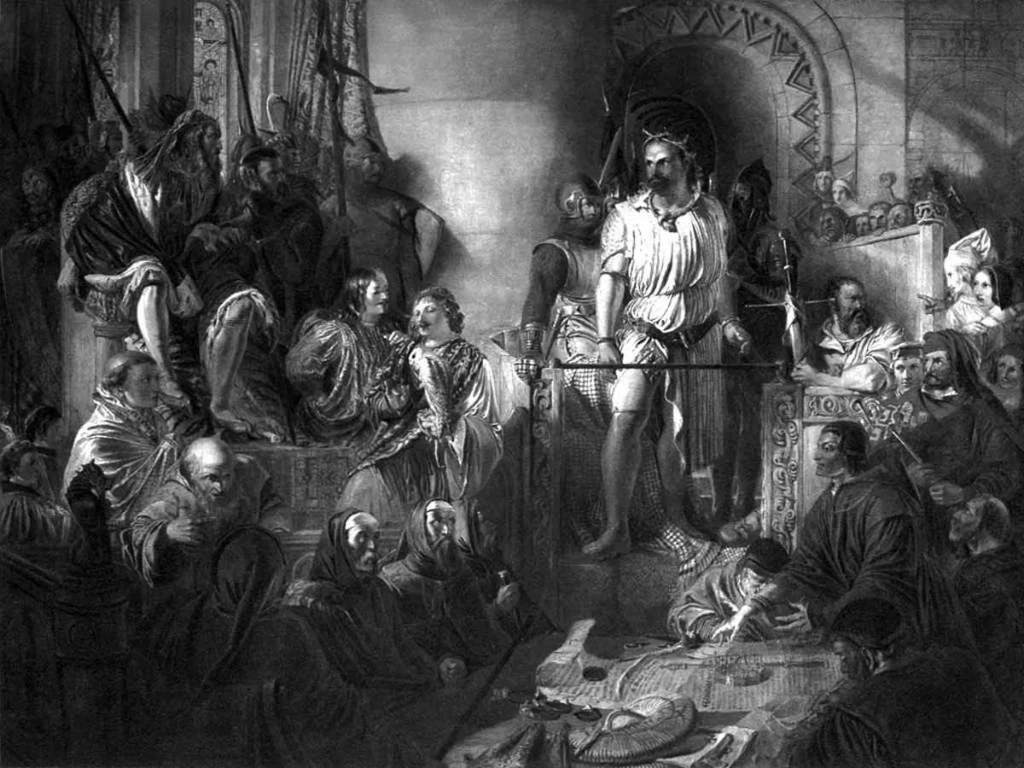

Tower, Trial, and Death

In the Tower, More wrote letters to his daughter, Meg. Cromwell visited and urged him to take the oath. More stood firm.

His trial began on July 1, 1535. The jury included Anne Boleyn’s relatives. The verdict came in just 15 minutes: guilty of high treason. The normal punishment was to be hanged, drawn, and quartered, but Henry commuted it to beheading.

On July 6, 1535, at Tower Hill, London, Sir Thomas More was executed. He was 57.

Why He’s So Controversial

- Conscience vs. King: More chose conscience over obedience to Henry VIII. To Catholics, he is a martyr who died for the faith. To others, he was a top official who refused the national choice to break with Rome.

- Power at the Peak: As Lord Chancellor, he was the kingdom’s highest judge and Henry’s chief civilian officer during a violent religious shift. His actions and inactions mattered greatly.

- Public Silence, Private Belief: More tried to keep his stance private, but in a revolution, silence can be seen as resistance. His refusal to take the oaths put him on a direct collision course with royal power.

The Mind Behind Utopia

Beyond politics, More was a leading humanist thinker. His book Utopia (1516) imagined a model society and sparked debates across Europe about law, work, religion, and justice. Friends like Erasmus praised his mind. Even his enemies respected his intelligence.

What His Story Shows

Thomas More’s life is the heart of a Tudor tragedy: a loyal servant rises to the top, but the rules of power change. Henry VIII demanded religious obedience as well as political loyalty. More could only give the second. His refusal made him a traitor in law—and a hero to those who believed the Church must stand above the king.

Key Timeline (At a Glance)

- 1478: Born in London

- 1502: Called to the Bar

- 1504–1514: Enters Parliament and royal service; becomes Privy Councillor

- 1521: Knighted; under-treasurer of the Exchequer

- 1525: Speaker of the House of Commons

- 1529: Becomes Lord Chancellor

- 1530–1532: Refuses to support annulment and supremacy; resigns

- 1533–1534: Declines Anne Boleyn’s wedding; refuses oaths; imprisoned

- July 1, 1535: Tried and found guilty of treason

- July 6, 1535: Executed at Tower Hill

Final Word

Sir Thomas More was brilliant, brave, and stubborn. He served his king with skill, but he would not betray his conscience. That choice cost him his life—and secured his place as one of the most influential, and most controversial, figures in Tudor England.