On the morning of April 25, 1859, roughly 150 men gathered near Damietta on Egypt’s northern coast and swung their pickaxes into the earth. It was not just another day of labor on the Nile Delta; it was the first stroke in an audacious plan to pierce the isthmus of Suez and stitch two seas together. At the center of this gamble stood Ferdinand de Lesseps—a French diplomat with the tenacity of an engineer and the vision of a merchant—who had dreamed since the 1830s of a direct, saltwater corridor joining the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. If it worked, Europe’s ships would no longer need to loop the Cape of Good Hope to reach the Indian Ocean. If it failed, the desert would swallow fortunes and reputations alike.

What followed was a decade of politics, epidemics, feuds, forced labor, and machine-toothed progress. Yet the dream was older than de Lesseps, older even than Napoleon. In truth, the story of the Suez Canal is as ancient as Egypt’s own fascination with water, trade, and the alchemy of turning sand into passage.

A Very Old Idea

Long before steam dredgers clawed at Bitter Lakes, Egyptian rulers imagined waterways linking the Nile to the Red Sea. Classical writers say that Pharaoh Necho II (610–595 BCE) began a canal and that Darius of Persia later carried the work forward. Herodotus insists that “a hundred and twenty thousand Egyptians perished” in the digging, while Diodorus Siculus noted that Darius halted the work, worried—wrongly, as we now know—that the Red Sea sat higher than Egypt and might flood the land. The Ptolemies were said to finish an ancient version, using a clever lock to tame water levels.

Modern scholarship places the earliest Nile–Red Sea channels around the 1850s BCE, as irrigation and navigation routes threaded through Wadi Tumilat and the Bitter Lakes. Centuries later, Trajan would extend the canal for commerce across Rome’s African and Arabian frontiers. The passage waxed and waned with empires. Under the Byzantines it declined. By around 760 CE, the Abbasid caliphs deliberately closed it to choke supplies to rebellious holy cities. Still, the memory of a river-sea artery endured, so much so that when Napoleon Bonaparte swept into Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century, he searched the sands for its bones.

Napoleon’s Glance and a Miscalculation

In 1798, Napoleon had strategic reasons to dream of Suez. A canal could shrink the world and, with it, Britain’s grip on India and the East. He sent engineers and scholars to survey the isthmus, hoping for a definitive “yes.” What he got instead was a debilitating no. His chief engineer, Jacques‑Marie Lepère, misread the difference in sea levels, exaggerating the Red Sea’s rise at high tide by nearly 10 meters (33 feet). If true, a direct sea‑to‑sea cut would drown the delta.

The error lingered like a curse. For decades, the “French ditch” would seem like fantasy on paper and disaster in practice. But ideas, like rivers, have a way of finding their channels.

Saint‑Simonians, Surveys, and a Young Engineer’s Straight Line

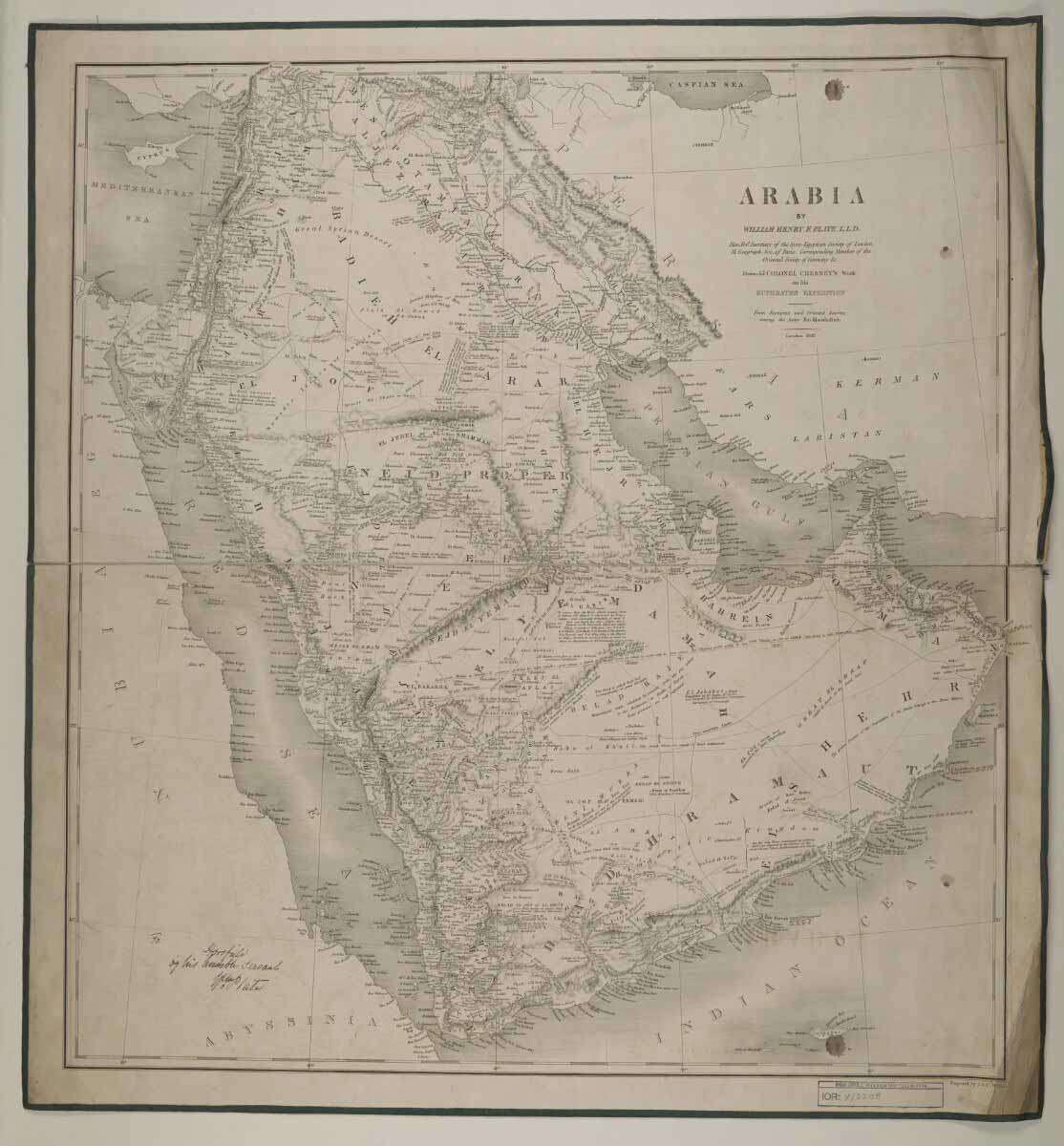

By the 1830s, the project found new champions among Saint‑Simonian disciples who believed science and industry could remake society. They organized the Société d’Études du Canal de Suez in 1846, sending teams to examine every dune and basin between the seas. Their verdict upended Lepère’s: the Mediterranean and the Red Sea sat at essentially the same level. The principal question was not “flood” but “route.”

Here, the civil engineer Luigi (Alois) Negrelli sketched the most elegant answer: a direct, sea‑level canal from the Mediterranean’s rim to the Red Sea, avoiding elaborate locks and expensive detours. The proposal was bold, practical—and politically explosive. Great Britain balked. So did Abbas Pasha, the Egyptian khedive, who feared entanglement and foreign leverage. For the moment, the sands held.

A Diplomat with a Shovel: De Lesseps Steps In

Enter Ferdinand de Lesseps, former French consul in Cairo and a man with a talent for friendship. During his earlier posting he had grown close to Said Pasha, son of the viceroy. When Abbas Pasha died in 1854, Said ascended—and de Lesseps saw his opening. On November 30, 1854, he secured a concession to found a company that would cut the canal and administer it for 99 years after completion, at which point ownership would revert to Egypt.

The concession was only paper. To carve reality, de Lesseps needed money, men, and permission. He set off across Europe selling his vision to investors and statesmen. He won polite nods and some subscriptions—especially in France—but ran headlong into a wall in London.

More Stories

Britain’s Great Debate—and a Feud of Engineers

To many Britons, a canal through Suez looked like a shortcut to Asia; to Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, it looked like trouble. He feared the project would imperil the Ottoman Empire’s delicate balance, hand France influence in Egypt, and prove technically unsound. “Bubble schemes,” he sneered, a dig at what he considered speculative follies dressed as progress. The British public argued the matter in Parliament and the press. Robert Stephenson, the celebrated engineer of railways, sided with Palmerston and picked apart Negrelli’s assumptions in 1857–1858, declaring the plan flawed and the obstacles too great.

Negrelli answered in kind through articles and open letters—some in the Österreichische Zeitung, others echoed in the Times—insisting that the canal could and should be built. The exchange hardened into a transnational feud: two engineers arguing not only about slopes and silt but about the very boundaries of possibility. Fate cut the argument short; both men died before victory could be claimed. History has since given its verdict: the straight, sea‑level canal Negrelli imagined is the one ships steam through today.

Company of the Canal

De Lesseps countered politics with process. In 1855, he formed an International Scientific Commission to reassess every prior survey and produce a definitive plan. After months of work on the ground, the commission in 1857 endorsed Negrelli’s design. A second concession followed in 1858, and de Lesseps finally launched the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez—the Suez Canal Company. He offered 400,000 shares at 500 francs each. French citizens subscribed enthusiastically. Other nations hesitated, leaving a large tranche unsold until Said Pasha himself purchased them, taking on heavy loans to keep the dream afloat.

Even then the spade could not yet bite. British diplomats in Constantinople pressed the Ottoman sultan to withhold approval. Work stalled. It took the direct weight of Napoleon III—France’s emperor—to pry loose the permissions and let the enterprise proceed.

Ten Years in the Sand

April 25, 1859: the first blows fell on the northern reaches near the Nile. Early excavation was almost biblical in its simplicity—pickaxes, baskets, bare hands. Men stood waist‑deep in water, scooping mud for hours. The working conditions were brutal. Although some workers received wages under the Egyptian administration or directly from the company, coerced labor was widespread; foremen used the threat—and sometimes the fact—of the whip to hurry the lines.

Politics slowed the project; so did cholera, which in 1865 swept through the region and forced work to a crawl. Yet a mechanical revolution was arriving on site. As the 1860s wore on, fleets of dredgers and steam shovels replaced human chains, gnawing their way through flats and salt marshes that hand labor could not conquer fast enough. Bitter Lakes became basins; dunes became cuts; the terrain began to admit a future that maps had promised.

By August 1869, a decade after the Damietta start and at a cost more than double the original budget, the two seas kissed through a man‑made mouth. The channel totaled a staggering 73 million cubic meters (97 million cubic yards) of excavated earth—a void measured in human ambitions.

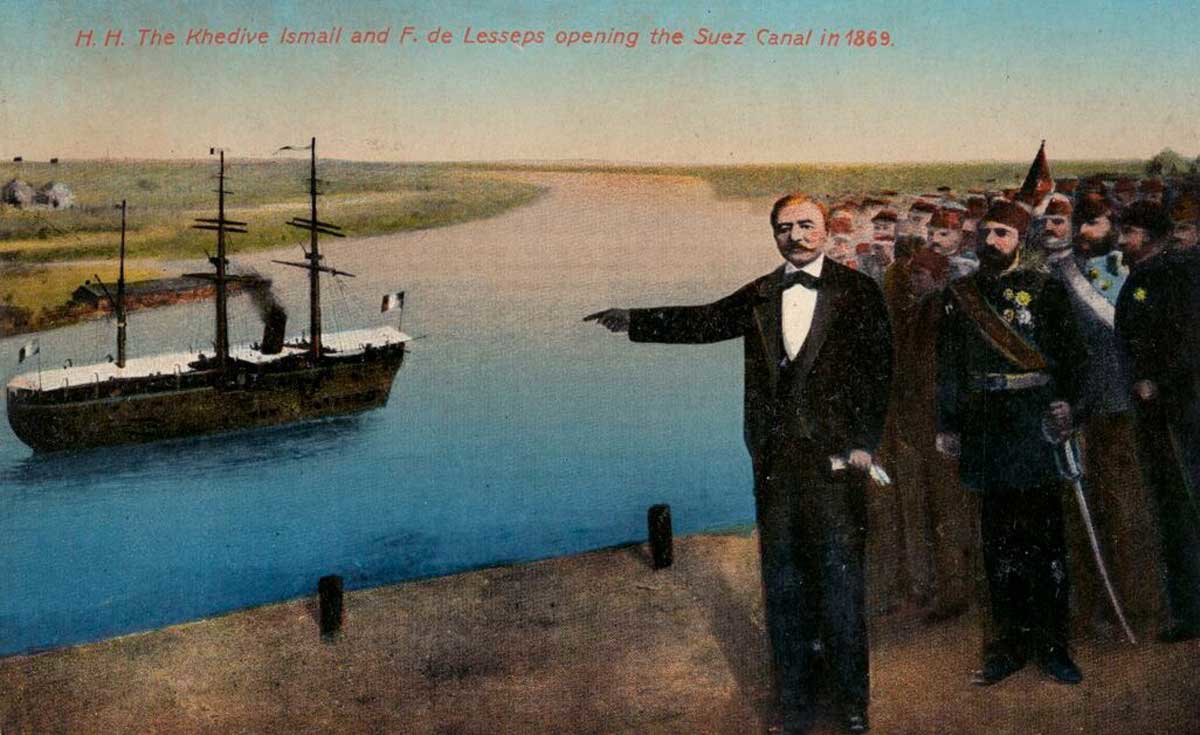

Opening Day: November 17, 1869

The inauguration unfolded like a scene from an opera because, in a sense, it was meant to be one. Empress Eugénie’s yacht, L’Aigle, led a procession of dignitaries through the new waterway as fireworks punctuated desert skies and balls glittered late into the night. The khedive, Ismail Pasha, had even commissioned Giuseppe Verdi to write an opera for the occasion. But history intervened; the Franco‑Prussian War and the Siege of Paris delayed the sets. The opera house staged Rigoletto instead, while Aida—the commission—would arrive later as a separate triumph.

Symbolism aside, a canal is judged by ships, not by soirées. In its first two years, traffic disappointed. Depths and widths at several points made navigation tricky for larger hulls. Between 1870 and 1884, roughly 3,000 ships ran aground or stranded along the passage. But improvements in 1876 deepened and widened the channel. The current began to flow the way investors had imagined.

Irony sailed at the head of the queue: the majority of early traffic flew the British flag. And when Egypt’s finances buckled in 1875, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli seized the moment for Britain and bought the khedive’s shares, securing a commanding stake in the canal company and, with it, leverage over the route that Palmerston had once mocked.

A Corridor that Redrew the Map

Once the technical kinks were smoothed, the Suez Canal did what its builders had promised: it collapsed distance. Steamers shaved weeks off voyages between Europe and Asia, redirecting trade lanes, naval strategy, and the geopolitics of empire. Insurance tables changed; coaling stations sprouted; port cities from Port Said to Aden felt new currents of commerce.

But the canal also bound Egypt’s fate to global powers more tightly than ever. Control over a ribbon of water became a proxy for control over routes, markets, and, ultimately, sovereignty. In 1956, nearly a century after the first dredger chugged into Bitter Lakes, Egypt asserted authority over the waterway in the Suez Crisis, nationalizing the canal and confronting Britain, France, and Israel in a showdown that signaled a new post‑imperial era.

The People in the Story

Histories of grand projects tend to list engineers and rulers; they must also remember workers. The Suez Canal was not only a feat of science and diplomacy; it was a human ordeal. Many came for wages; many more were compelled. Men toiled in water and salt, their feet softened and infected, their backs bent under baskets of mud. Epidemic and exposure shadowed the work. The canal’s later elegance—its straight blue satin on a map—owes itself to those whose names did not make it into the ledgers.

There were thinkers, too, who changed the course without touching a shovel. Negrelli’s insistence on a sea‑level canal simplified construction and reduced costs. The Saint‑Simonians kept the flame lit when politics tried to snuff it. Stephenson’s criticism, though misplaced in hindsight, forced more rigorous surveying and accounting. Palmerston’s resistance revealed how infrastructure is never just engineering—it is foreign policy by other means.

And then there was de Lesseps, indefatigable, controversial, sometimes blithe about labor realities, but unarguably the canal’s chief evangelist. His letters bristle with salesmanship and defiance; in one he advised a confidant to stir opinion in England because “heaven helps those who help themselves.” He helped himself to allies, to headlines, to the machinery of an age hungry for speed. The canal bears his imprint as surely as the excavators’ teeth left theirs in the sand.

Climax: When Two Seas Met

Every long narrative has a click—the instant when possibility turns into presence. For Suez, that moment arrived when the final shoals yielded and Mediterranean water curled into the Red Sea. A hundred problems did not vanish; they merely changed shape. Yet in that flow you can hear the sound of a nineteenth‑century world reorganizing itself: new trade patterns, fresh calculations of power, a compression of geography that would make global interdependence both easier and more fraught.

The canal’s climax was not just the elegant procession of 1869; it was the first night a captain set his course not around a continent but through a continent, and realized the sea itself had been taught a new path.

Aftermath: From Doubt to Dependence

If the opening was the crescendo, the years that followed were the coda—full of adjustments, disputes, and the steady normalization of what once seemed impossible. The canal demanded constant maintenance: dredging, widening, depth management, and navigational rules to prevent future strandings. Insurance underwriters rewrote risk. Maritime law evolved to handle choke points that were neither fully national nor fully international in character.

Meanwhile, the canal reshaped Egypt’s finances and politics. The loans that underwrote early shares and later modernization helped trigger the debt crisis that let Britain purchase stakes and later assert deeper control. The waterway’s very success made it a prize to be contested—a lesson underscored in the twentieth century when national control became a litmus test of decolonization.

Yet there is also a quieter aftermath: the way the canal slipped into the ordinary. In the present century, a missile cruiser gliding down the Suez can seem routine—just another line in a naval log. That routinization is itself the measure of the canal’s triumph. What once required an admiral’s daring now needs a pilot’s checklist.

What the Suez Canal Teaches

The Suez Canal is a story about scale—how small tools, small letters, and small design decisions add up to a transformation visible from orbit. It teaches that miscalculations can haunt generations, that politics can stall or save a project, and that machines can expand human reach while also magnifying human costs. It shows how infrastructure sits at the intersection of commerce and conscience.

It also reminds us that progress rarely moves in a straight line, even when the canal does. Ancient channels opened and closed; medieval rulers rewrote the map for reasons of strategy; modern surveyors fought in newspapers as much as in boardrooms; and the nineteenth‑century diggers wrestled with disease and desert to deliver a twentieth‑century world.