By AD 235, the Roman Empire seemed invincible. It stretched from the misty moors of Britain to the sun-baked sands of Mesopotamia, held together by paved roads, professional legions, and the unifying aura of the emperor. But prosperity hid fault lines: a bloated bureaucracy, mounting defense costs, and succession built more on intrigue than law.

⚔️ Assassination of Severus Alexander: The Spark

On March 18, 235, soldiers in Mainz murdered Emperor Severus Alexander after he tried to buy off Germanic raiders instead of fighting. The throne passed to Maximinus Thrax, a rough soldier-emperor with no senatorial pedigree. His violent accession shattered the illusion that emperors were semi-divine figures chosen by fate; now any ambitious commander with swords behind him might grab the purple.

🌀 Fifty Years, Fifty Emperors

Between 235 and 284, Rome cycled through over 60 claimants to the throne, many reigning mere months. Legions on the Rhine or Danube hailed their own generals, pushing rival armies toward Rome. Civil war became a grim routine; coin mints scrambled to strike new portraits before old ones melted down.

Key moments:

- Year of Six Emperors (238): Gordian I & II, Pupienus, Balbinus, Gordian III, and Maximinus Thrax all claimed rule—four died violently within months.

- Valerian’s Capture (260): Emperor Valerian was seized alive by the Persian king Shapur I—an unthinkable humiliation that rocked Roman confidence.

- Gallienus’ Reforms (253-268): Often mocked in ancient sources, Gallienus nevertheless barred senators from military commands and promoted equestrian officers, planting seeds for a more professional high command.

🏚️ Economic Meltdown

Wars drained the treasury, forcing emperors to debase silver coins with copper. Inflation soared: a soldier’s annual pay in AD 200 bought three months of grain by AD 270. Price instability eroded tax revenues, while trade caravans avoided war zones, slashing customs income.

Visible symptoms:

- Barter Revival: In the provinces, farmers demanded cloth or wine instead of worthless coins.

- Proto-Feudal Ties: Big landowners offered protection to smallholders in exchange for labor, foreshadowing medieval manorialism.

🌊 Triple Waves of Invasion

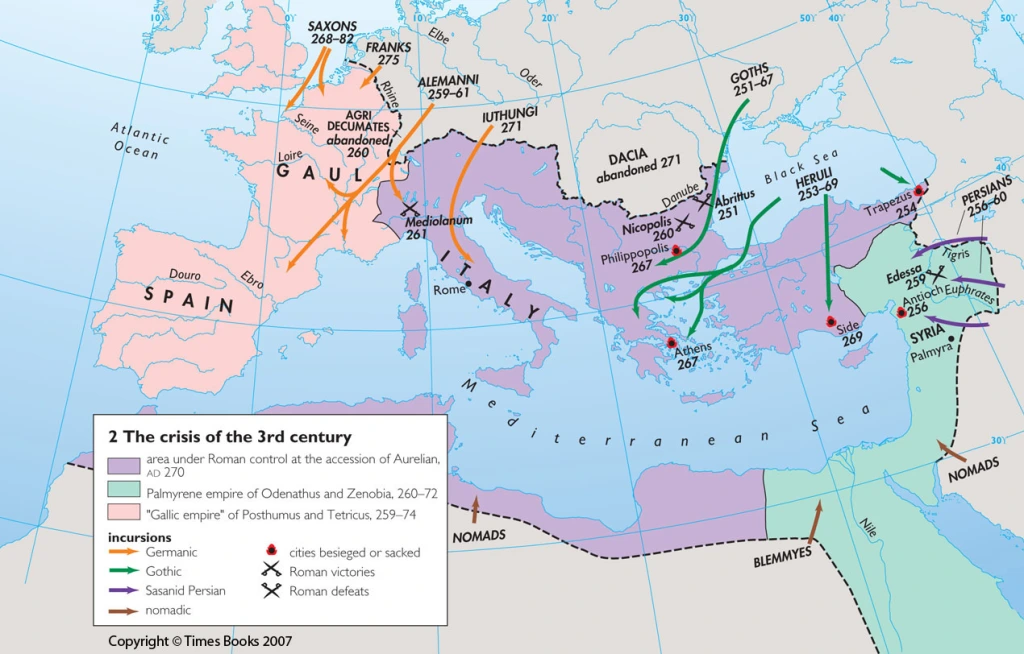

While Romans killed Romans, external foes sensed weakness:

- Germanic Confederations: The Alamanni pressed the Upper Rhine; the Goths burst across the Danube, even sacking Athens in 267.

- Sassanid Persia: Shapur I raided Syria and captured Antioch twice.

- Seaborne Raiders: New Gothic fleets and Caucasian pirates ravaged the Black Sea and Aegean islands.

Frontier forts fell, towns built emergency walls, and refugees clogged Italy’s roads, spreading panic and plague.

🛡️ Military Evolution

Necessity drove innovation. Gallienus created the first large cavalry reserve stationed at Mediolanum (Milan), able to gallop to threatened fronts. Command structure tightened: the dux (duke) emerged, leading combined-arms forces on specific sectors rather than entire provinces.

These reforms, honed by later emperors, birthed the comitatenses (field armies) and limitanei (border troops) of Late Rome—flexible enough to firefight multiple crises.

👑 Breakaway Realms

As centripetal forces failed, two regions seceded for survival:

- Gallic Empire (260-274): Founded by Postumus, stretching from Britain to Hispania. It minted its own coins and repelled German incursions while Rome writhed.

- Palmyrene Empire (267-272): Led first by Odaenathus and then his widow Queen Zenobia, Palmyra controlled Syria, Egypt, and much of Asia Minor, guarding the East against Persia.

Both separatist states maintained Roman bureaucracy and culture, but their existence highlighted how far the center had lost authority.

⚒️ Aurelian: “Restitutor Orbis” – Restorer of the World

Enter Lucius Domitius Aurelianus—Aurelian—emperor from 270 to 275. In five whirlwind years he:

- Defeated the Goths and built the Aurelian Walls around Rome (many sections still stand).

- Crushed the Palmyrene Empire, capturing Zenobia near the Euphrates.

- Reconquered Gaul, ending the breakaway Gallic Empire.

- Reformed coinage with a higher-silver antoninianus, the aurélianus, and outlawed corrupt mint officials.

- Promoted the cult of Sol Invictus (“Unconquered Sun”) as a unifying imperial religion—foreshadowing Constantine’s use of Christianity.

Assassinated en route to Persia, Aurelian proved a single vigorous ruler could still knit the empire, but deeper structural fixes were needed.

🏢 Diocletian’s Tetrarchy

The crisis officially ends with Diocletian’s accession in AD 284, but its lessons sculpted his reforms:

- Tetrarchy: Two senior Augusti and two junior Caesares shared power, reducing coup temptations.

- Tax Overhaul: A census-based land tax supplied frontier troops directly.

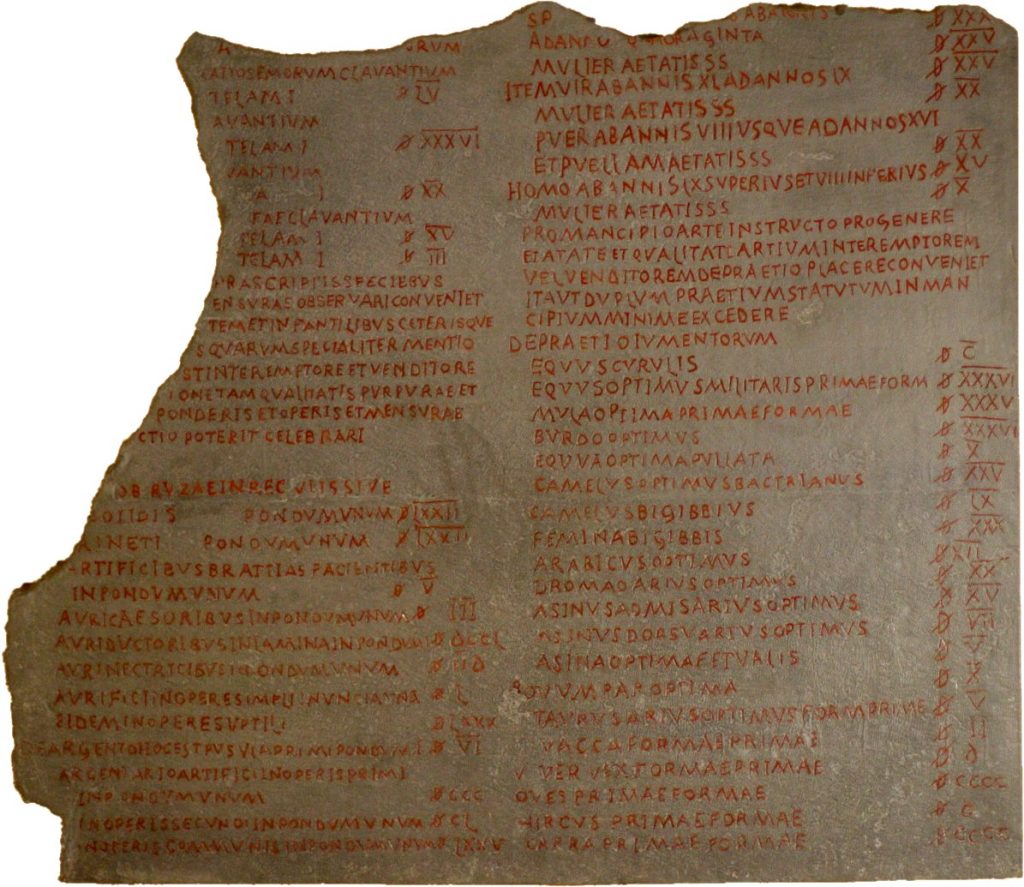

- Price Edict (301): A doomed attempt to freeze wages and prices, revealing how hard inflation was to tame.

- Administrative Splitting: He divided provinces into smaller units for tighter control, supervised by diocesan vicars.

Though the Tetrarchy collapsed after Diocletian’s retirement, the framework birthed the Late Roman state that survived in the East another thousand years.

📊 Everyday Life in Freefall

- Urban Flight: As city amenities faltered, elites relocated to fortified rural villas; baths closed for lack of fuel.

- Religious Ferment: Mystery cults, Christianity, and eastern deities gained converts searching for stability amid chaos.

- Plagues: Epidemiologists believe at least two major outbreaks (possibly smallpox or measles) ravaged populations already weakened by famine.

- Artistic Shifts: The classical style gave way to rigid, symbolic forms—seen on the Arch of Gallienus—mirroring a society prioritizing message over aesthetics.

🌟 Long-Term Legacy

- Birth of the Dominate: Emperors adopted jeweled crowns, court ritual, and divine titles—autocracy over collegiality.

- Foundation of the Medieval Economy: Villa self-sufficiency and tenant labor foreshadowed feudal manors.

- Christianity’s Opening: Social disarray made universal faiths attractive; by Constantine’s reign, Christianity could step into the ideological vacuum.

- East–West Divergence: Resources funneled toward the more defensible, wealthier East—setting up the later split of Empire and Church.

💡 Insert image: Late Roman mosaic of Sol Invictus – Caption: “A new divine face for a battered empire.”

🗺️ Touring the Crisis Today: A Mini-Travel Guide

| Site | Modern Location | What to See |

|---|---|---|

| Aurelian Walls | Rome, Italy | 19 km of brick ramparts & Porta Asinaria gate |

| Postumus’ Capital | Trier, Germany | Imperial throne room (Aula Palatina) later reused by Constantine |

| Palmyra Ruins | Homs Governorate, Syria | Colonnaded street & Temple of Bel (safety permitting) |

| Diocletian’s Palace | Split, Croatia | Fortress-palace now forming the city’s old town |

📚 Further Reading

Potter, David. The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395 – panoramic survey of crises and recoveries.

Bray, John. Gallienus: A Study in Reformist and Sexual Politics – revisionist take on a maligned emperor.

Southern, Pat. The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine – clear narrative for newcomers.

🔚 Conclusion: The Empire That Refused to Die

The Crisis of the Third Century was Rome’s darkest hour—a half-century when emperors perished faster than coins could be struck, borders buckled under barbarian pressure, and the economy teetered on collapse. Yet out of chaos emerged adaptation: mobile armies, new administrative layers, and spiritual horizons that would define Late Antiquity.

Rome survived not because it was unbreakable, but because it was flexible—a lesson as relevant to modern institutions as to ancient legions. When you walk Rome’s 1,700-year-old Aurelian Walls or gaze at Diocletian’s seaside palace, remember they were built by men who stared into the abyss and decided the empire was worth saving.