It was a crisp autumn evening in Munich on September 30, 1938. Inside the grand chambers of the Führerbau, four men emerged from hours of tense negotiation with a document they believed would preserve peace in Europe. They smiled for the cameras, shook hands, and spoke of diplomacy. But behind the smiles, history was shifting. What had just been signed was not peace, but the ignition key to the deadliest war humanity had ever known.

The Munich Agreement was supposed to stop a war. Instead, it fed a dictator’s hunger and showed the world that appeasement would not tame Adolf Hitler—it would only embolden him.

To understand how Europe arrived at this moment, we must step back to the ruins of World War I. The Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919, redrew the map of Europe, carved up empires, and birthed new nations. Among them was Czechoslovakia, a patchwork state composed of Czechs, Slovaks, Germans, Hungarians, and others. Within its western border lay the Sudetenland—a mountainous, industrial region home to over three million ethnic Germans.

These Sudeten Germans had not asked to become part of Czechoslovakia, and though the new state granted them citizenship, tensions simmered. By the 1930s, Adolf Hitler seized upon this discontent as part of his larger plan to unite all German-speaking peoples under the Third Reich. But his ambition did not end with unification—it pointed squarely toward expansion.

By 1938, Hitler had already swallowed Austria through the Anschluss, a bloodless annexation that alarmed many but provoked no military response. Emboldened, he turned his gaze to the Sudetenland. The Nazi press churned out stories of alleged Czech oppression of ethnic Germans. Hitler thundered at rallies that he would protect his “fellow Germans,” no matter what. And in London and Paris, leaders began to sweat.

At the heart of it all stood British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. A well-meaning man, Chamberlain believed that another great war would be catastrophic. He had lived through the carnage of the First World War and saw diplomacy as the only way to avoid repeating history. So, when Hitler demanded the Sudetenland, Chamberlain—alongside French Premier Édouard Daladier—flew to Germany to talk.

Czechoslovakia, notably, was not invited to the meetings that would decide its fate. Its president, Edvard Beneš, watched from the sidelines as the Western powers negotiated away a chunk of his nation. The Czechs were told they must accept the decision—or face war alone.

In Munich, on the night of September 30, Chamberlain, Daladier, Hitler, and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini reached an agreement. Germany would be allowed to annex the Sudetenland. In return, Hitler gave a vague promise that he had “no more territorial demands” in Europe.

Chamberlain returned to London the next day waving the agreement, famously declaring he had secured “peace for our time.” Crowds cheered. Headlines praised diplomacy. But the world had been deceived.

More Stories

Just six months later, Hitler broke his promise. In March 1939, German troops marched into Prague and took over the rest of Czechoslovakia. There was no pretense of protecting German speakers this time—it was naked conquest. The illusion of Hitler as a reasonable statesman evaporated overnight.

The Munich Agreement had not stopped a war. It had merely delayed it. Worse, it had signaled to Hitler that Britain and France were unwilling to fight. This emboldened him further, convincing him that the West would back down again when he turned toward Poland.

Winston Churchill, who had opposed the Munich Agreement from the start, delivered a bitter verdict in the House of Commons: “You were given the choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor, and you will have war.”

Indeed, war came. On September 1, 1939, Hitler invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany. World War II had begun—not because of Munich alone, but Munich had made it all but inevitable.

For the Czechs, the Munich Agreement was a betrayal. They lost not only the Sudetenland but also critical border defenses and industrial capacity. Without firing a shot, Hitler had crippled the Czechoslovak state. The country was carved up, first by Germany, then by Hungary and Poland. And when Nazi tanks rolled into Prague in 1939, no one came to stop them.

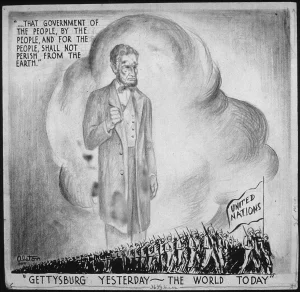

The lessons of Munich have echoed through the decades. The word “appeasement” became synonymous with weakness. Western leaders, haunted by Chamberlain’s miscalculation, vowed never to repeat it. During the Cold War, American presidents cited Munich to justify firm stances against the Soviet Union. In modern times, it still serves as a cautionary tale in diplomacy.

But the story is not just about failure. It is also a deeply human story—of leaders trying desperately to avoid catastrophe, of citizens cheering the promise of peace, and of a continent sleepwalking into disaster. Chamberlain was no villain. He was a man of his time, shaped by the trauma of the past and hopeful for a peaceful future. His mistake was not in wanting peace, but in misjudging the man he faced.

Hitler, by contrast, saw diplomacy not as a tool for peace, but as a weapon of war. Each agreement he signed was a step toward conquest. He lied, he manipulated, and he exploited the West’s desire for calm.

The Munich Agreement remains one of history’s pivotal turning points—not because of what it prevented, but because of what it permitted. It is a stark reminder that not all peace is peace, and not all agreements buy time.

Sometimes, they buy blood.