Roses are everywhere—gardens, weddings, paintings, perfumes. But the story of the rose is long and surprising. It begins millions of years ago and runs through myth, medicine, politics, and modern breeding. Here’s a simple tour.

Ancient Roots

Fossils show rose-like plants in the northern hemisphere between 33 and 23 million years ago. These early roses already had the traits we still recognize: five petals, oval serrated leaves, and colorful fruit (hips). They grew in mild climates full of insects—conditions roses still love today.

Myths & Meanings

Greek and Roman stories gave the rose powerful symbols. In one tale, the flower goddess (Chloris/Flora) creates the rose, Dionysus/Bacchus gives it fragrance, and Aphrodite/Venus connects it with love. Eros/Cupid presents a rose to Harpocrates, the god of silence, to keep secrets. From here comes sub rosa—“under the rose”—meaning confidential. People carved roses into ceilings of halls, courts, and confessionals to remind everyone: what’s said here stays here.

The First “Scientific” Rose

In 1883, paleobotanist Charles Leo Lesquereux described Rosa hilliae from fossil beds in Colorado. He named it for Charlotte Hill, a homesteader who collected and shared the area’s fossils with scientists. It’s a nice reminder: amateurs have often helped write the history of science.

From Wild Shrub to Garden Star

Today the genus Rosa has about 150 species and thousands of varieties. Many of our garden roses come from a small group of Asian species crossed over time with European and American wild roses. Broadly, people speak of three groups:

- Species (wild) roses – simple five-petaled flowers

- Old roses – introduced before 1867

- Modern roses – bred since then

Familiar wild species include Rosa canina (dog rose) common in hedges, Rosa pimpinellifolia (Scotch rose) tough in windy coasts, Rosa gallica from warmer southern Europe, and North American types like Rosa carolina and Rosa blanda.

Early Cultivation & Uses

People have grown roses for a very long time. In China, roses were deliberately cultivated by around 3000 BCE for rosewater, perfume, medicine, and celebration. Confucius noted roses in the Imperial gardens by 500 BCE and many books on them in the emperor’s library. China also gave the world yellow roses—European wild roses did not have that color.

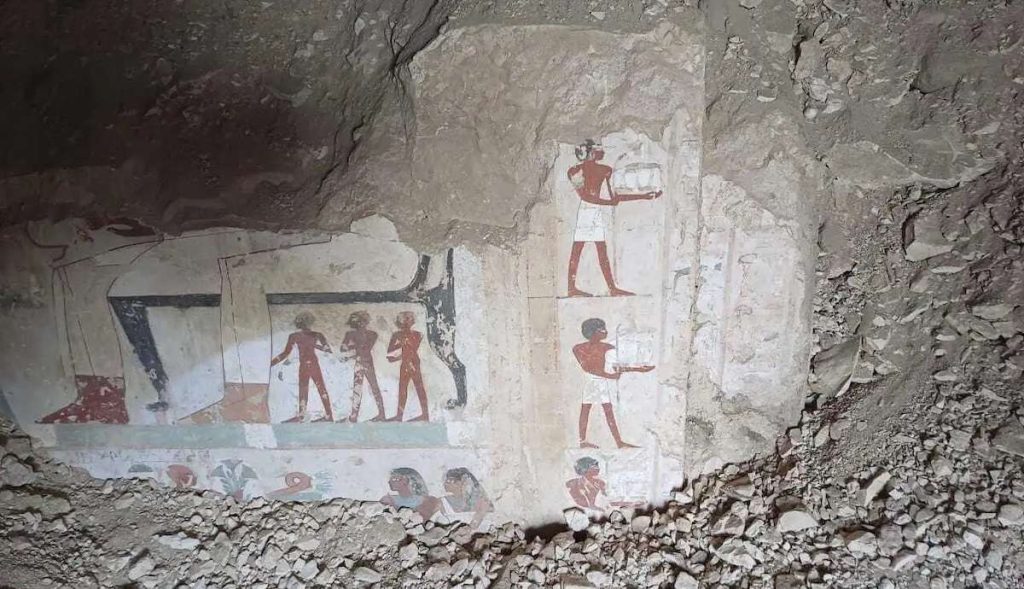

Ancient Egyptians bathed in rosewater and scattered petals to scent rooms. Romans planted public rose gardens. In medieval Europe, nobles and monasteries grew roses for ceremony and healing. Two old favorites spread widely:

- Rosa damascena (the damask rose), likely brought from Syria in the Crusader era—double, richly scented flowers.

- Rosa officinalis (the apothecary’s rose), prized for remedies.

Old roses don’t bloom as long as many modern hybrids and their colors are softer, but they’re hardy, low-maintenance, and very fragrant. Because varieties don’t stay true from seed, gardeners keep a favorite by taking cuttings—so an “old rose” today can be a living link to medieval gardens.

Politics in the Petals

Roses also carried political meaning. In 13th-century England, Eleanor of Provence used the white rose (Rosa alba) as her badge. Her son Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, used the red rose (Rosa gallica). Later, Richard, Duke of York, chose a white rose. When the Houses of Lancaster (red) and York (white) fought for the crown (1455–1487), history called it the Wars of the Roses. Peace came when the Lancastrian Henry Tudor became Henry VII and married Elizabeth of York—uniting red and white into the Tudor rose, a double emblem carved on buildings and furniture to signal a united kingdom.

Centuries later, in 1986, the United States chose the rose as its national flower. President Ronald Reagan’s proclamation praised it as a symbol of life, love, beauty, and memory—and noted America’s long history of growing roses, from George Washington’s own breeding to the White House Rose Garden.

A European Passion & a French Boom

In the 1500s–1600s, Dutch growers developed Rosa centifolia, the “cabbage rose,” with many petals and a flat, full face—famous in Dutch Old Master paintings. The real explosion came in early 1800s France, led by Joséphine de Beauharnais at Malmaison, who gathered roses from across Europe even during wartime. She hired artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté to paint them in Les Roses (1817–24), a priceless record for science and gardeners. French breeders like Jacques-Louis Descemet spread and refined roses such as Rosa gallica, fueling a national craze. Many “old roses” grown today were bred in this period.

The Hybrid Age: China Changes Everything

A major turning point arrived around 1790 when repeat-flowering China roses reached Europe. Unlike most European roses that bloomed once, these could flower again and again. Breeders quickly crossed them with local roses, unlocking new colors, forms, and the prized remontant (repeat) habit.

Key steps:

- Tea roses: crosses involving Rosa chinensis and Rosa gigantea; said to smell like a cup of China tea—elegant, long-flowering.

- Hybrid perpetuals: damask and other species crossed for big flowers and years of blooming.

- Hybrid tea: mid-19th-century cross of tea roses with hybrid perpetuals—large, classic blooms and a long season. This became the most popular rose class worldwide.

Other lineages added richness:

- Bourbon roses: a natural cross between a China rose and a damask rose on Île Bourbon (Réunion). Brought to Paris in the early 1800s and crossed further with Rosa gallica, they are long-blooming and strongly scented.

- Noisette roses: the first American-bred group, born in South Carolina when John Champneys crossed ‘Old Blush’ (a China rose) with the climbing Rosa moschata. Seeds traveled back to France, creating new climbing Noisettes, later crossed with tea roses.

Modern Roses: Shape, Color, Display

The modern era began with hybrid teas, then added:

- Floribundas: compact shrubs with clusters of many flowers, developed by crossing dwarf China roses with small hybrid teas (popularized by breeders like the Danish Poulsen family).

- Grandifloras: mid-20th-century crosses between hybrid teas and floribundas—tall, hardy bushes with big blossoms. They’re today’s garden staples: reliable, colorful, and showy, though often less fragrant than old roses.

Every year, breeders release new hybrids aiming for the perfect mix of flower form, rebloom, fragrance, disease resistance, and color. Meanwhile, species roses preserve the original gene pool, and old roses keep their loyal fans for natural growth and deep perfume.

Why the Rose Endures

The rose survives because it adapts. It can be simple or complex, wild or manicured, symbolic or simply beautiful. It holds many stories at once:

- Nature’s survivor from deep time

- A symbol of love and secrecy

- A political badge that helped end a civil war

- A scientific and artistic subject from Redouté to modern labs

- A garden favorite shaped by centuries of careful breeding

Walk through any park or flip through any art book and you’ll meet these layers—the wild five-petaled ancestor, the scented old garden blooms, the modern hybrids blazing with color. All are chapters of the same, long story: how a tough shrub with simple flowers became the world’s most beloved blossom.