Sekigahara (1600) didn’t just decide who won Japan’s civil wars. It decided what “being a samurai” would even mean after the fighting stopped.

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s victory cleared the last major obstacle to his rise, and the Tokugawa shogunate that followed produced something Japan hadn’t enjoyed in generations: long, enforced stability. The price of peace, though, was identity shock. A whole warrior class—men trained from childhood to kill, to lead, to die—now had to live in a country where “battlefield success” was no longer a career path.

So what did the samurai become when the war ended?

If you want a clean answer, you won’t get one. But you can watch the transition happen through a handful of people—some famous, some oddly forgotten—who each reveal a different way Japan tried to reinvent itself under pressure: pressure from internal politics, from ideology, and eventually from the West.

Here are six lives—spanning the Tokugawa peace to the moment Japan cracked open to the modern world—that show how a warrior society tried to evolve without losing its spine.

1) William Adams: The Outsider Who Became a Hatamoto

The Tokugawa world begins, strangely enough, with a shipwrecked Englishman.

William Adams arrived in Japan in 1600 aboard the Liefde—the lone survivor of a disastrous expedition. He wasn’t a missionary. He wasn’t a conqueror. He was a sailor and shipbuilder, and that made him valuable in a Japan that was still deciding what to do with Europeans.

Tokugawa Ieyasu interviewed him, extracted strategic information about European rivalries, and then did something wildly unusual: he kept Adams close. Adams was eventually made a direct vassal—hatamoto—and given the Japanese name Miura Anjin. His expertise helped the Tokugawa build Western-style ships and strengthen naval know-how at the exact moment the regime was consolidating power.

Adams’ story matters because it sets the tone for early Tokugawa pragmatism: curiosity without surrender, extraction without dependence. Japan wasn’t “closed” yet—not in the later, hardened way people imagine. It was testing the world, cautiously, with a ruler’s cold eye.

2) Hasekura Tsunenaga: A Samurai Crosses the World—Then Comes Home to a Different Japan

A decade after Sekigahara, the Tokugawa system still had room for bold experiments.

Hasekura Tsunenaga—retainer to Date Masamune of Sendai—was chosen to lead what became known as the Keichō Embassy. The mission left Japan in 1613 and ultimately reached Spain and Rome, where Hasekura met Pope Paul V. It was a diplomatic gamble aimed at trade, status, and—entangled with it all—Christianity.

This is the part that feels almost cinematic: a samurai walking through Mexico City, then European courts, then the Vatican—representing a Japan that was still deciding whether it wanted to be a player in the global system.

But the real tragedy (and lesson) is what happened when he returned.

The Tokugawa regime hardened. Fear of foreign influence deepened. Christianity, once a negotiable factor in certain domains, became a threat to be crushed. The same state that could once entertain a global embassy would soon enforce a tightly controlled gate—trade corralled, religion hunted, contact rationed.

Hasekura’s life becomes a snapshot of a window that opened—and then slammed shut.

3) Miyamoto Musashi: Winning the Peace Through Method

Musashi is the name everybody knows: the undefeated duelist, the sword saint, the man mythologized into near-superhuman status.

But the Musashi that matters for the Tokugawa era isn’t just the fighter—it’s the writer.

His Go Rin no Sho (The Book of Five Rings) isn’t a romantic ode to honor. It’s a manual of effectiveness. It argues for adaptability, for reading terrain and timing, for not getting emotionally attached to a single weapon or a single idea. In a world where samurai could no longer prove themselves in mass battle, Musashi’s philosophy became a way to turn combat into something transferable: strategy, discipline, perception.

That’s why Musashi keeps resurfacing in business books and leadership talks. Not because he was a cool swordsman—because he translated violence into method.

And near the end of his life, he distilled something even harsher: Dokkōdō (“The Way of Walking Alone”), a set of precepts about detachment and acceptance—less about winning fights than about not being owned by desire, comfort, or fear.

In the Tokugawa peace, Musashi represents one survival strategy for the warrior class: turn the blade inward, turn skill into principle.

4) Yamamoto Tsunetomo: When “Loyalty” Turns Into a Trap

If Musashi is the practical philosopher, Yamamoto Tsunetomo is the cautionary tale.

Most modern ideas of “Edo bushidō” get filtered through Hagakure (“Hidden Leaves”), a collection of reflections dictated by Tsunetomo and compiled by Tashiro Tsuramoto. It’s messy, fragmentary, intense—and famous for lines that push absolute commitment and daily meditation on death.

Under Tokugawa stability, that rhetoric had a certain appeal. When the world stops demanding battlefield courage, some people compensate by raising the idea of courage to a religion. You can feel the anxiety behind it: the fear that samurai identity is dissolving, that softness is creeping in.

But here’s the danger: ideas don’t stay in the century that produced them.

Concepts like absolute loyalty and fearlessness in the face of death can be used to produce integrity—or to justify fanaticism. Later Japanese nationalism would selectively weaponize that tone, turning “devotion” into an ideological engine.

So Tsunetomo’s legacy is double-edged: a spiritual attempt to preserve purpose, and a reminder that romanticizing death can be politically exploitable.

5) Shinmi Masaoki: Samurai Diplomacy Meets Industrial Power

By the mid-1800s, the Tokugawa peace had a new enemy: time.

Two centuries of controlled stability created order—but also stagnation. Then the Black Ships arrived. Commodore Matthew Perry forced the issue in 1853, and Japan’s leaders could no longer pretend the ocean was a wall.

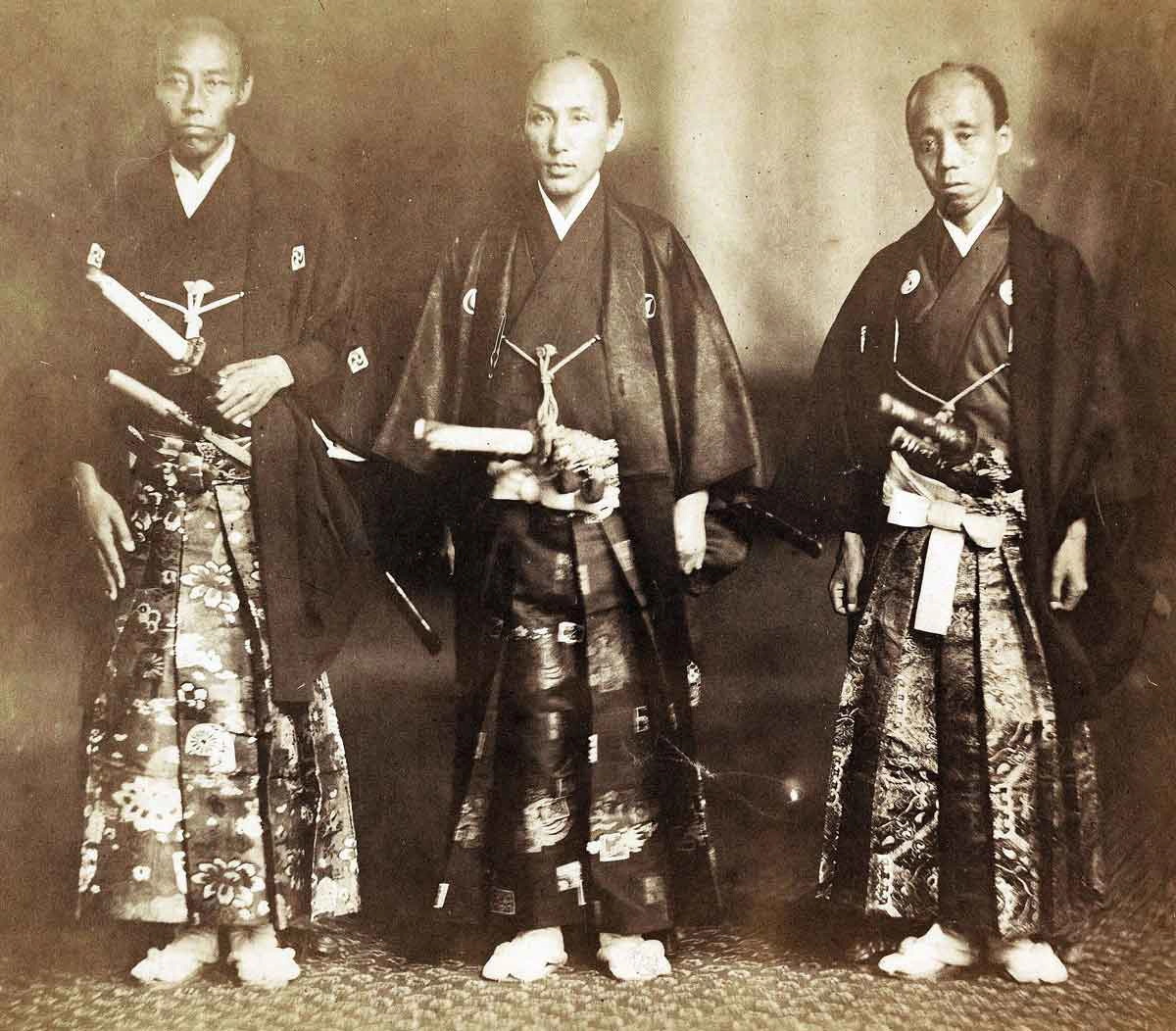

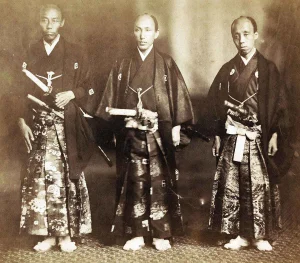

In 1860, the shogunate sent the first Japanese diplomatic mission to the United States—an event that reads like a culture shock on fast-forward. Three plenipotentiaries are typically highlighted: Muragaki Norimasa, Shinmi Masaoki, and Oguri Tadamasa. They met President James Buchanan, carried treaty business, and—equally important—were stared at by crowds who couldn’t believe these “exotic” visitors wore swords with formal dress.

And then there’s the signal to the world: the Kanrin Maru, a Japanese warship, crossing the Pacific to demonstrate Japan could operate modern navigation and ship technology.

This is the samurai class trying to do something it was never designed for: survive geopolitics through diplomacy, technology, and image. The blade is still there—but now it rides beside paperwork, engines, and treaties.

6) Sakamoto Ryōma: The Samurai Who Helped End the Samurai World

If one name gets called a “founder of modern Japan,” it’s Sakamoto Ryōma.

He was born into a lower-ranking samurai family in Tosa, which mattered a lot in a rigid Tokugawa hierarchy. His era wasn’t about proving yourself in war; it was about navigating status ceilings, clan politics, and a system that felt increasingly outmatched by the outside world.

Ryōma’s genius wasn’t that he was the strongest swordsman. It was that he could connect enemies.

He helped mediate the Satsuma–Chōshū alliance—the political engine that would eventually topple the Tokugawa order. And he didn’t just talk politics. He moved resources.

In 1865, Ryōma founded a trading and shipping organization in Nagasaki called Kameyama Shachū, later known as the Kaientai—often described as one of Japan’s first modern-style corporations, blending commerce with a private naval function.

That detail matters: Japan didn’t modernize through philosophy alone. It modernized through logistics—ships, guns, supply chains, training, institutions that could compete in an industrial world. Ryōma understood that if Japan didn’t build capacity fast, it would become China in the Opium Wars: pressured, carved up, humiliated.

So Ryōma becomes the ultimate Tokugawa-era irony:

A samurai who helped build the coalition that ended samurai rule.

The Samurai Didn’t Disappear—They Mutated

People like to talk about “the end of the samurai” as if it happened in one dramatic scene.

But it was a long transformation.

- Adams shows the early Tokugawa regime absorbing foreign skill without surrendering control.

- Hasekura shows how open the door briefly was—before fear shut it.

- Musashi shows how warfare turned into transferable discipline.

- Tsunetomo shows how identity anxiety can harden into ideology.

- Shinmi shows samurai stepping onto the world stage with treaties and steamships.

- Ryōma shows the final pivot: from clan loyalty to national survival through modernization.

In other words: the Tokugawa peace didn’t kill the warrior class. It forced it to evolve.

And that evolution—messy, brilliant, sometimes dark—is one reason Japan could pivot so quickly once history stopped granting it the luxury of isolation.