The Seljuks were a Turkic people who rose from nomadic origins on the Central Asian steppes to establish a vast and influential empire across Western and Central Asia. Their story, beginning with a breakaway tribe, reveals a fascinating transformation from pastoralist warriors to rulers of a sophisticated, settled civilization.

Origins and Nomadic Life on the Steppe

In the late 10th century, a chief named Seljuk led his tribe, part of the Oghuz Turks, away from their Khazar overlords near the Caspian Sea. This marked the start of a significant migration southwards from modern-day Kazakhstan into Iran and Azerbaijan. Before their empire, the Oghuz Turks lived a traditional pastoralist life on the vast, harsh Central Asian steppes. They relied on their herds of horses, sheep, and goats for sustenance, living off dairy products like milk, yogurt, cheese, and kimiz (fermented mare’s milk). Women played a vital role in textile production, weaving wool into fabrics and kilims.

Like other nomadic groups such as the Mongols, the Oghuz had strong tribal and clan ties. Seljuk and his clan belonged to the respected Kinik tribe. Their society valued warriors and horse archers, and inter-tribal warfare was common, alongside the formation of alliances. Seljuk himself was likely a mercenary or chief serving the powerful Khazars. Following a disagreement or possibly Seljuk’s conversion to Islam, his tribe migrated. His grandsons, Tughril and Chağri bey, would eventually lead the Oghuz to form the Great Seljuk Empire, named after their ancestor.

Life and Legacy of the Great Seljuk Empire

Upon conquering major cities like Nishapur, Merv, and eventually besieging Baghdad, Tughril and Chağri found themselves ruling over settled, sophisticated populations. To maintain power, they had to adapt from their nomadic, raiding lifestyle to a sedentary one. This involved adopting Persian culture, seen as more refined, and changing their titles from beys to Sultans. They replaced their felt tents with palaces and commissioned significant architecture like caravanserais, mosques, and madrasas, often incorporating Persio-Islamic styles such as the Persian dome.

The Seljuk court was multilingual. While Turkic men dominated the military, administration was largely handled by Persians, making Persian the lingua franca of the empire. It was used for literature, including popular epics like the Shahnameh. Arabic remained crucial as the language of Islamic theology and jurisprudence.

Women’s roles also shifted. Nomadic Oghuz women were highly active, involved in animal tending, textile production, riding, and even using weapons. As some Seljuks settled, women spent more time in domestic roles. However, powerful women like Inanch Hatun and Terken Hatun held significant influence as advisors, administrators, and commanders.

The Great Seljuks officially adhered to Sunni Islam, learning from Persian and Sufi scholars. However, their semi-nomadic followers often blended Islamic beliefs with older pagan and shamanistic practices, sometimes viewing Sufi saints as replacements for traditional shamans. This blending was also seen in Seljuk art, which featured human figures in miniatures and sculptures, often depicting figures in traditional steppe attire, despite common Islamic discouragement of such imagery. The empire was a melting pot of cultures (Turkic, Persian, Arab), though Turkic culture was less adopted by local settled populations. The Seljuks patronized learning, leading to significant advances in science and philosophy under figures like Omar Khayyam and Al-Ghazali.

[block id=”related”]

Decline and Continuation

By the early 12th century, the Great Seljuk Empire faced internal strife, including rivalries between powerful figures and succession disputes leading to internecine wars. External pressures mounted from the Crusades in the west and revolts by other Turkic tribes and dynasties in Central Asia. The final blow came with a revolt by the Oghuz, the Seljuks’ original followers, in 1153. Following the death of the last Sultan in the Iranian branch in 1154, the empire fragmented.

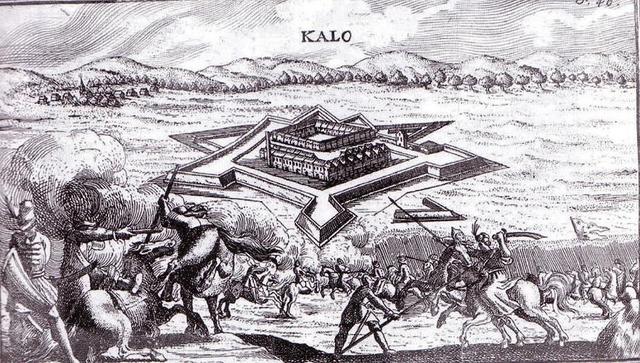

Its most notable successor state was the Sultanate of Rum, or the Anatolian Seljuks, in modern-day Turkey. This branch continued many of the Great Seljuks’ administrative and cultural traditions in a Byzantine Anatolian context. However, they too eventually succumbed to the pressures of Mongol invasions and internal revolts, dissolving by the early 14th century.

In conclusion, the Seljuks represent a compelling case study of a nomadic group transitioning to imperial rule. Their ability to adapt culturally, govern complex societies, and synthesize Turkic, Persian, and Islamic traditions created a powerful empire whose legacy, particularly through the Anatolian Seljuks, had a profound impact on the history and culture of Western Asia.