When English settlers planted their first crops along the Chesapeake in the early 1600s, they discovered a perfect storm for Nicotiana tabacum: long, humid summers, sandy loam soils, and rivers that bled straight into the Atlantic’s shipping lanes. Tobacco was fickle—ruining the land after just three plantings—but its global price soared.

In Europe, smoking had leapt from curiosity to craze, and nothing earned more silver per pound than a cured Virginia leaf. Within a decade, colonists were measuring wealth not in acres but in hogsheads of “sot-weed,” turning the Chesapeake into what newspapers would soon call the “Tobacco Coast.”

🧭 Mapping the Chesapeake

Curving shorelines, deep natural ports, and a spiderweb of tidal creeks let planters roll barrels straight onto shallops and sloops. Unlike New England’s tight townships, settlement sprawled in thin ribbons along riverbanks; neighbors might be ten miles apart yet just a canoe-ride away.

This watery topography welded local economies to trans-Atlantic merchants. Plantation wharves looked outward—to London, Bristol, and Lisbon—long before they looked inland to the Alleghenies.

🌱 John Rolfe and the Jamestown Experiment

The big bang moment came in 1612 when John Rolfe smuggled Caribbean “Orinoco” seed into Jamestown. Unlike the harsh native variety, Orinoco’s sweet smoke captivated Londoners. The very next year Rolfe shipped four barrels, earning returns that dwarfed fur, timber, or sassafras. By 1617 Virginia exported 20,000 pounds; by 1629 it cracked 1.5 million. Investors clamored for land patents, fantasy estates were drawn on parchment, and London’s Virginia Company boasted it had found “the commodity of kingdoms.”

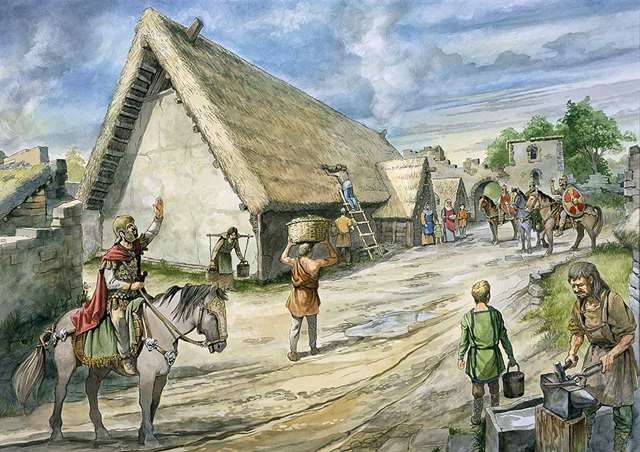

🧑🌾 The First Labor Backbone

Tobacco was labor-hungry: every stalk had to be planted, worm-picked, topped, cut, and fire-cured by hand. England’s landless poor saw opportunity. In exchange for four to seven years of toil, an indentured servant got passage, board, and—if he survived malaria—50 acres of frontier.

Between 1630 and 1680, roughly two-thirds of all English migrants to America walked off a slave ship’s deck in iron but with a labor contract, not a lifetime sentence. Servants fueled an economy where a single good year could catapult a yeoman into the planter class.

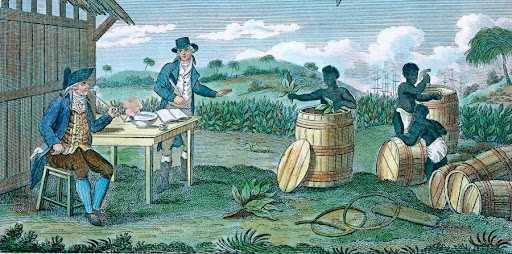

⛓️ From Servitude to Slavery

By the 1680s mortality rates dropped and life expectancies rose; indentured laborers now lived long enough to claim their freedom farms, tightening land supply. Planters pivoted to permanent, inheritable bondage—enslaved Africans purchased through the Royal African Company. The demographic needle moved swiftly: in Virginia enslaved people made up 10 percent of the population in 1680; by 1750 they were 40 percent. Tobacco’s relentless demand standardized the brutal gang-labor system—sun-up to sun-down work under an overseer’s lash—and stitched slavery into America’s economic DNA.

💡 Insert image: Detail of a 1700s plantation ledger listing enslaved workers – Caption: “Human beings counted like acreage and livestock.”

🏠 Plantation Worlds

A mature Tidewater plantation resembled a self-contained village: the owner’s great house fronted the river for easy loading; a line of weather-boarded “tobacco houses” cured the crop; slave quarters and service buildings sprawled inland. Wealth expressed itself in imported mahogany furniture, Delft tiles, and the latest London fashion journals, yet the engine was always a thin green plant and the enslaved hands that nursed it from seedbed to cask.

🚢 Smoke, Credit, and Empire

Each autumn barrels were rolled onto ships bound for Bristol or Glasgow, and the Chesapeake entered a web of credit capitalism. London merchants advanced goods—cloth, books, Madeira wine—on next year’s crop, trapping planters in a debt spiral but flooding the coast with luxuries. Tobacco taxes funded the Royal Navy, tea warehouses, and even the crown’s wars. In effect, Chesapeake planters became both cogs and shareholders in the rise of the British Empire.

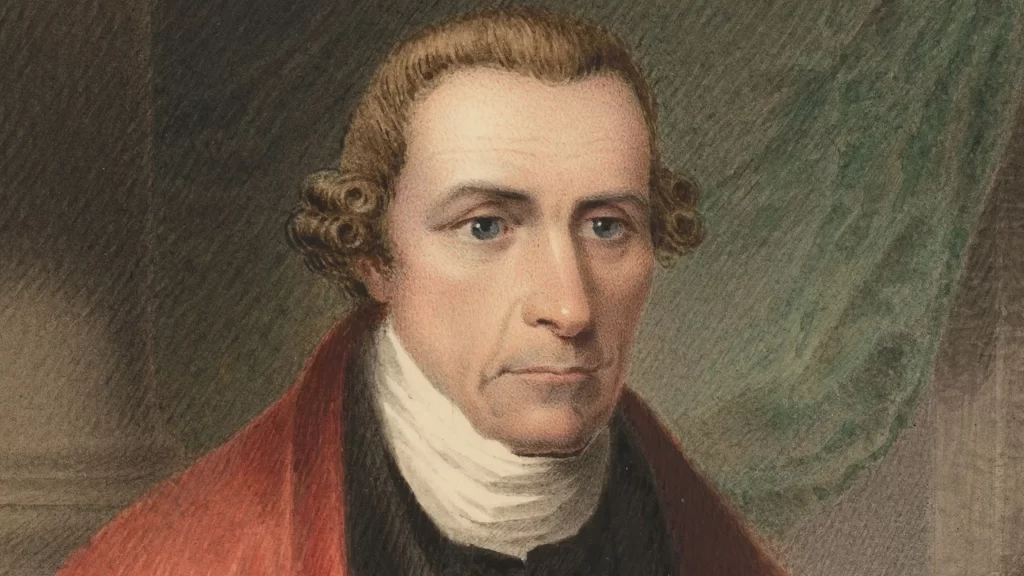

💰 Smoke and the Seeds of Revolution

Ironically, the same merchant ties that enriched planters also kindled rebellion. When Parliament tightened the Navigation Acts and slapped duties on molasses, iron, and finally tea, Virginian aristocrats felt the pinch first. Tobacco prices sagged in the 1760s; debt mounted. Fiery orators like Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson framed independence as a chance to trade on their own terms. In 1775, half the signers of the Declaration had fortunes rooted in Chesapeake tobacco.

🌳 Environmental Toll

Tobacco is a nutrient vampire. After three crops, fields turned yellow and yields tanked. Planters reacted not with fertilizer but with migration, chopping new clearings—first up the James and Potomac valleys, then across the Appalachians into Kentucky and Tennessee. The endless search for fresh loam drove Native dispossession, spurred road building like the Great Wagon Road, and welded the agrarian South to an expansionist mindset that would echo through the 19th century.

🍂 Culture of the Leaf

By the 1700s tobacco shaped daily routines from Paris salons to tribal councils. Chesapeake gentry preferred pipes with yards-long clay stems—cooler smoke and a handy status symbol. Fine ladies kept gold snuff boxes, flicking dust beneath lace cuffs. Even George Washington mixed his own personal blend, complaining when shipments arrived moldy. Meanwhile, enslaved workers carved corn-cob pipes for meager nighttime breaks, fashioning a parallel, hidden culture around the same crop that chained them.

⚔️ Civil War and Cotton’s Overtake

Although cotton eventually eclipsed tobacco as King Cash of the South, the older crop never vanished. In the Civil War era, Union blockades strangled Confederate exports, and the wartime shortage of cigars in Europe reminded financiers how entwined leaf and politics remained. Post-war, bright flue-cured tobacco from the Carolina Piedmont wrote the next chapter—Durham’s Bull Durham and Richmond’s Lucky Strike—but the Chesapeake had already stamped its pattern on American labor systems and global trade.

🧭 Visiting the Tobacco Coast Today

| Site | State | Why Go |

|---|---|---|

| Jamestown Island | VA | Archaeology reveals the very pits where Rolfe’s first plants grew. |

| St. Mary’s City | MD | Re-created 1630s tobacco fields with costumed interpreters. |

| Shirley & Berkeley Plantations | VA | Riverfront mansions still flanked by original curing barns. |

| Port Tobacco Village | MD | Once the second-largest seaport in Maryland—now a quiet hamlet with a story to tell. |

🏛️ Conclusion

Tobacco was never just an agricultural commodity. It reshaped coastlines, reordered labor, seeded representative politics, and bankrolled an empire—all before the first musket cracked at Lexington. Its legacy is carved into courthouse records, slave cemeteries, and the meandering paths of America’s earliest highways. Stand on a Virginia bluff at sunrise, smell a barnful of curing leaves, and you can still feel the pulse of a world where fortunes blew in on a plume of fragrant smoke.

Key Takeaway for Readers: Today’s debates over cash crops, labor justice, and environmental stewardship are rehearsals of a 400-year-old drama first staged on the Tobacco Coast. Understanding that past equips us to script a better agricultural—and social—future.