The Tokugawa Shogunate (1603–1868), also known as the Edo Period, was a transformative era in Japanese history. Under the rule of the Tokugawa family, Japan experienced over two centuries of peace, stability, and isolation from much of the outside world. This period, marked by the sakoku (closed country) policy, fostered a unique cultural renaissance that shaped Japan’s identity and laid the foundation for its modernization.

🏯 The Rise of the Tokugawa Shogunate

The Tokugawa Shogunate emerged from the chaos of the Sengoku Period (1467–1603), a time of relentless civil wars among feudal lords (daimyo). Tokugawa Ieyasu, a strategic and patient warlord, unified Japan after his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. In 1603, he was appointed shogun by the emperor, establishing the Tokugawa Shogunate with its capital in Edo (modern-day Tokyo).

Ieyasu centralized power through a feudal system, balancing the authority of daimyo with loyalty to the shogunate. The sankin-kotai system required daimyo to alternate residence between their domains and Edo, ensuring their allegiance and draining their resources to prevent rebellion. This system, combined with a rigid social hierarchy, created the Pax Tokugawa—a period of unprecedented peace.

Statue of Tokugawa Ieyasu at Toshogu Shrine, symbolizing his enduring legacy.

🔒 Sakoku: The Policy of Isolation

The Tokugawa Shogunate implemented sakoku, a policy of national seclusion, to maintain stability and protect Japanese sovereignty. Beginning in the 1630s under Tokugawa Iemitsu, sakoku restricted foreign influence, banned Christianity, and limited trade to specific intermediaries. Japanese citizens were forbidden from traveling abroad, and most foreigners were barred from entering Japan, with violators facing severe penalties.

However, sakoku was not absolute isolation. Limited trade continued through the port of Nagasaki, primarily with the Dutch and Chinese via the artificial island of Dejima. The Dutch introduced rangaku (Dutch learning), allowing Japan to access Western knowledge in medicine, science, and technology. Diplomatic exchanges with Korea and the Ryukyu Kingdom also persisted, ensuring Japan remained selectively engaged with the world.

The sakoku policy shielded Japan from colonial threats posed by European powers like Spain and Portugal, preserving cultural integrity. Yet, it also limited technological advancements, setting the stage for challenges when Western powers forced Japan’s opening in the 1850s.

Dejima, the artificial island in Nagasaki, served as Japan’s window to the West during sakoku.

👥 Social Hierarchy and Control

The Tokugawa Shogunate enforced a strict social hierarchy to maintain order. Society was divided into four classes: samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants, with the samurai at the top and merchants at the bottom. Mobility between classes was prohibited, and each group had defined roles. Samurai, comprising about 6% of the population, served as warriors and administrators, while farmers, the backbone of the economy, produced rice to sustain the feudal system.

The shogunate promoted Confucian values, emphasizing loyalty, duty, and harmony. The sankin-kotai system further controlled daimyo by requiring them to leave family members in Edo as hostages. Peasants faced heavy taxation, but the absence of warfare allowed for agricultural improvements and population growth.

This rigid structure ensured stability but also created tensions. Merchants, despite their low status, gained wealth through commerce, challenging the samurai’s dominance. Over time, these economic shifts contributed to the shogunate’s decline.

Illustration of the Tokugawa social hierarchy, with samurai at the apex.

💹 Economic Growth and Urbanization

Despite its isolationist stance, the Tokugawa period saw significant economic growth. Agricultural advancements, such as improved irrigation and crop rotation, boosted rice production. The shogunate standardized coins, weights, and measures, facilitating trade. Road networks, including the Tokaido Road connecting Edo to Kyoto, enhanced commerce and communication.

Urban centers like Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto flourished, giving rise to a prosperous merchant class. Edo, with a population exceeding one million by the 18th century, became one of the world’s largest cities. The growth of commerce spurred industries like silk, cotton, paper, and sake brewing. A vibrant urban culture emerged, centered on entertainment districts known as the “floating world” (ukiyo), where merchants and samurai mingled.

However, economic disparities grew. Samurai, dependent on fixed stipends, struggled as inflation rose, while merchants amassed wealth. Peasant uprisings, driven by heavy taxation, became more frequent, signaling underlying tensions.

The Tokaido Road, a vital artery for trade and travel during the Edo Period.

🎭 Cultural Renaissance: Arts and Literature

The peace and prosperity of the Tokugawa era fostered a cultural renaissance. With internal stability, Japan turned inward, developing distinctly Japanese art forms and intellectual traditions. The ukiyo-e woodblock prints, depicting scenes from the floating world, became immensely popular. Artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige captured landscapes, kabuki actors, and urban life with vivid detail.

Kabuki theater and bunraku puppet theater thrived, offering entertainment that blended drama, music, and spectacle. The geisha, skilled in music, dance, and conversation, became cultural icons, providing refined companionship in entertainment districts. Literature flourished, with authors like Ihara Saikaku exploring themes of love and urban life in novels such as Five Women Who Loved Love.

Poetry, particularly haiku, reached new heights under masters like Matsuo Basho, whose works celebrated nature and transience. The spread of printing technology made literature and art accessible to a broader audience, democratizing culture.

Hokusai’s iconic ukiyo-e print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, exemplifies Edo Period artistry.

🖌️ Education and Intellectual Developments

The Tokugawa Shogunate prioritized education to support its Confucian ideology. The Shōheikō, a Confucian academy in Edo, trained samurai in Chinese classics and governance. Domain schools (hankō) educated samurai across Japan, while terakoya (temple schools) taught reading, writing, and arithmetic to commoners. By the late Edo Period, Japan’s literacy rate was among the highest in the world.

The kokugaku (National Learning) movement emerged as a reaction to Chinese influence, promoting the study of Japanese history, literature, and Shinto traditions. Scholars like Motoori Norinaga emphasized Japan’s unique cultural identity, laying the intellectual groundwork for nationalism.

Rangaku allowed limited access to Western knowledge, particularly in medicine and astronomy. This selective engagement ensured Japan was not entirely cut off from global advancements, preparing it for rapid modernization in the Meiji era.

A terakoya school, where commoners gained literacy and practical skills.

⚔️ Decline of the Tokugawa Shogunate

By the mid-19th century, the Tokugawa Shogunate faced mounting challenges. Economic disparities, peasant unrest, and the growing power of merchants weakened the feudal system. The sakoku policy, while preserving stability, left Japan technologically behind Western powers.

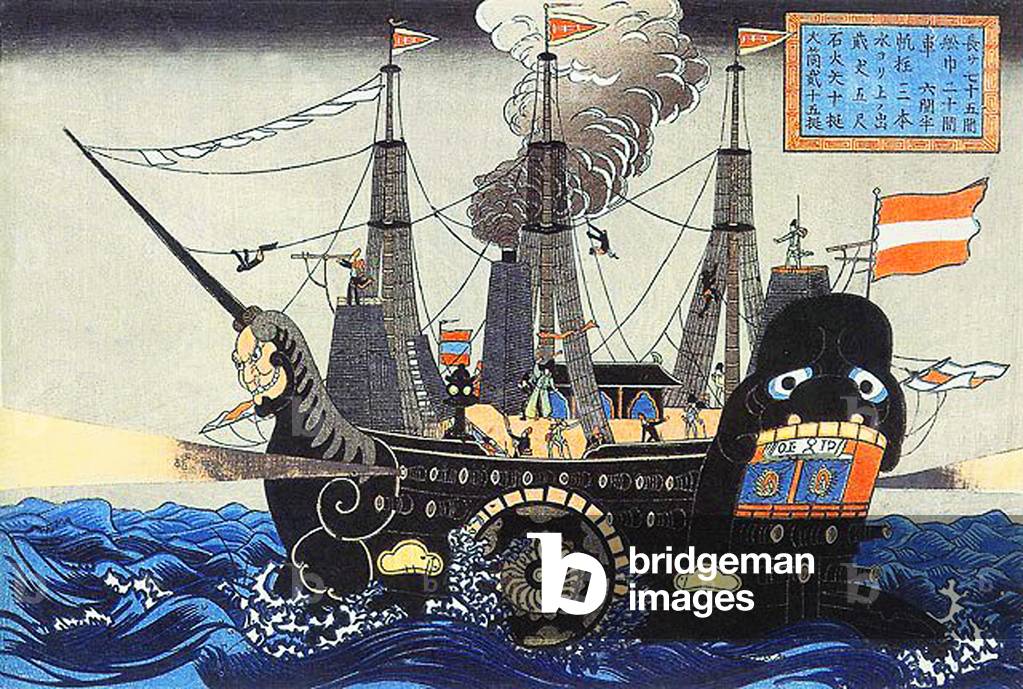

The arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry’s “Black Ships” in 1853 forced Japan to sign the Treaty of Kanagawa, opening ports to American trade. This exposed the shogunate’s inability to resist foreign pressure, eroding its authority. Daimyo and samurai, frustrated by the shogunate’s concessions, rallied around the emperor, leading to the Meiji Restoration in 1868, which toppled the Tokugawa regime and restored imperial rule.

The fall of the shogunate marked the end of feudal Japan, but its legacy endured. The cultural and intellectual developments of the Edo Period provided a foundation for Japan’s rapid modernization.

🌸 Conclusion

The Tokugawa Shogunate’s 250-year rule was a defining chapter in Japanese history. Its isolationist policies, while limiting technological progress, preserved cultural sovereignty and fostered a remarkable renaissance in arts, literature, and education. The peace and stability of the Edo Period allowed Japan to develop a distinct identity, which later fueled its transformation into a modern nation. The legacy of the Tokugawa era—its art, architecture, and intellectual traditions—continues to resonate in Japan and beyond, a testament to the enduring power of a culture shaped by isolation and creativity.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

The Enduring Unity and Adaptability of Christian Morality

Arsinoe IV: Cleopatra’s Forgotten Rival

Storms That Stopped the Mongols

Discover Michigan’s Historic Towns: The Top 10 Addresses

A Short History of Tobacco

How to Read the 6 Jane Austen Novels

The Seljuks: From Nomads to Sultans

Sami and Vikings: Life at Europe’s Far North

The Evolution of Ancient Egyptian Religion Across the Centuries

Machiavelli, Luther, and the Rise of Modern Moral Thought

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Britain’s Fight for Clean Air