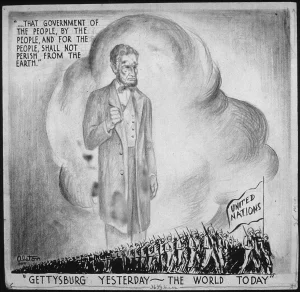

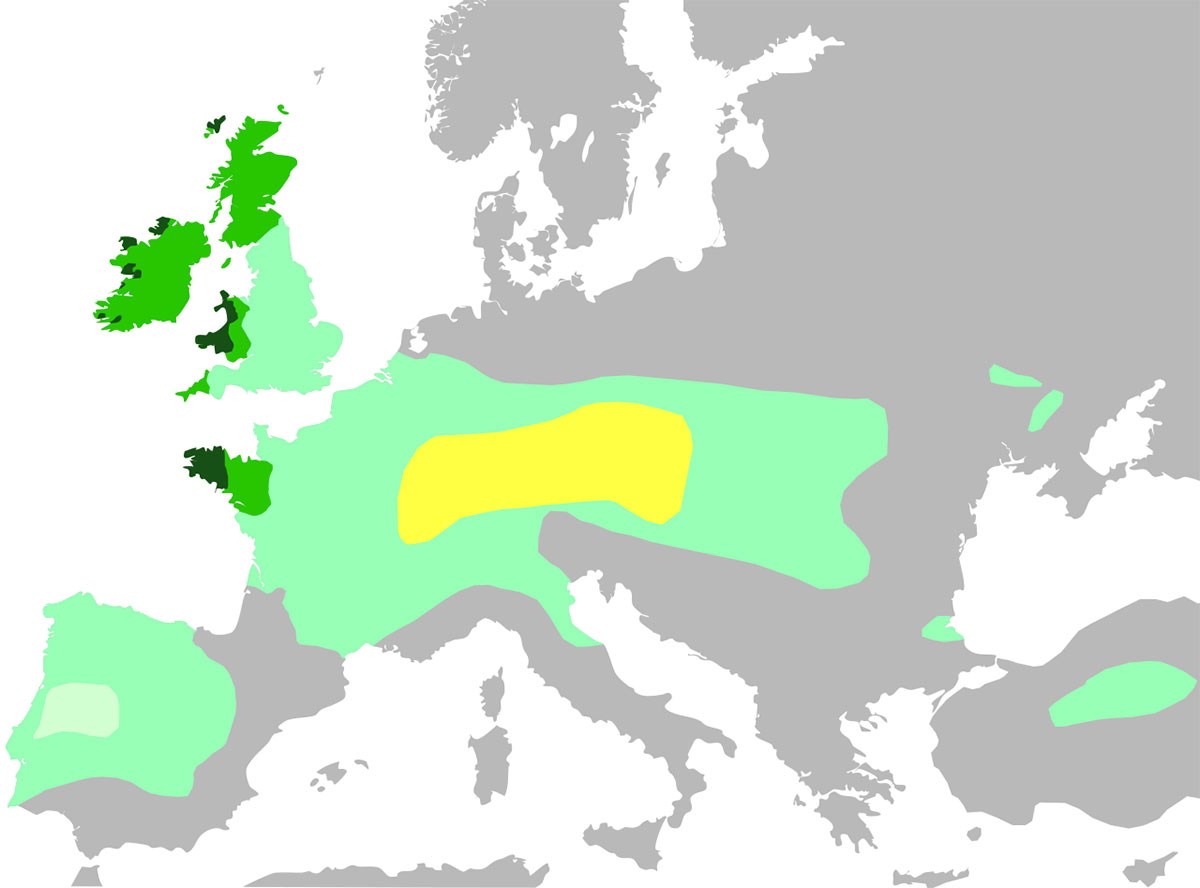

When most people think of the Celts, they picture misty hills in Ireland, druids in white robes, and windswept cliffs in Britain. But Celtic culture once stretched far beyond the British Isles. Celtic tribes spread across much of Europe – reaching all the way to what is now Portugal and Spain.

In northern Portugal, traces of these ancient people are still written into the landscape: stone hillforts, circular houses, warrior statues, and intricate metalwork. If you know where to look, you can walk through the remains of Celtic towns that stood long before the Romans arrived.

This post is your guide to that world.

Where Did the Celts Come From?

The Celts were not a single kingdom or empire. Between roughly 700 BCE and 400 CE, different Celtic-speaking tribes lived across a huge area of Europe, from parts of present-day Turkey in the east to the Atlantic shores of Portugal in the west.

Rather than one unified “Celtic nation,” they were a loose constellation of peoples who shared:

- Related Celtic languages

- Similar art styles

- Common religious ideas and funerary practices

Many historians trace their roots to Hallstatt, an archaeological site in modern-day Austria dating to the Bronze and early Iron Ages. From the 8th to the 6th centuries BCE, tribes in the Hallstatt region prospered thanks to valuable salt, iron, and copper deposits. Trade, intermarriage, and alliances helped spread their culture into western Austria, southern Germany, and what is now France.

Over time, this Hallstatt culture – and later the La Tène culture that followed it – evolved and moved outward. Part of that movement led southwest, toward the far edge of Europe: the Iberian Peninsula.

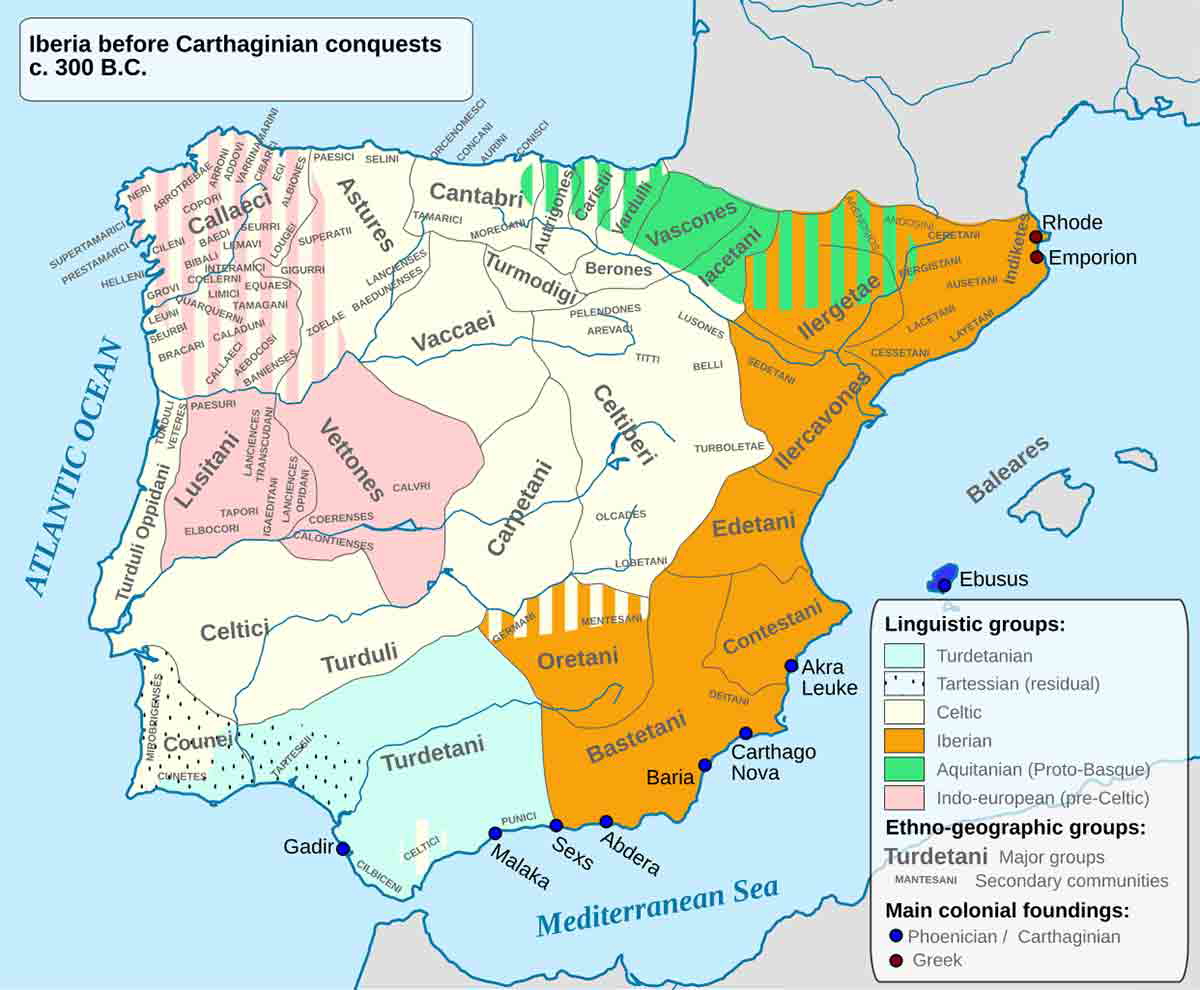

The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula

The first Celtic groups reached the Iberian Peninsula between the 8th and 6th centuries BCE. They settled in areas that are now northern and central Portugal and Spain.

There, they encountered other local peoples, including the Iberians and Lusitanians. Rather than simply replacing them, the Celts mixed and merged with them. This blending gave rise to Celtiberian cultures – societies that combined Celtic language and customs with local traditions.

Archaeology shows clear links between these Iberian Celts and the Hallstatt world. One of the most striking signs of this are the fortified settlements known as castros.

Castros and Civitas: Life in Celtic Portugal

Castros: Hillforts Above the Valleys

Castros were fortified hilltops chosen for their natural defenses and wide views over the surrounding countryside. Typically, they:

- Sat near water sources

- Wrapped around hills with stone ramparts, ditches, and stockades

- Often included water reservoirs to resist sieges

Inside, you’d find circular or sometimes rectangular houses made of local stone with thatched roofs supported by wooden beams. Floors were simple – packed earth or hardened clay.

Interestingly, although the Celts often lived in a tense, warlike environment, these hillforts were not always occupied full-time. Many seem to have been refuges, used in times of danger, rather than permanent homes.

Civitas and Oppida: Permanent Settlements

Alongside these hillforts, some larger, more organized settlements emerged. These are sometimes called civitas – permanently inhabited, planned communities with:

- Narrow, paved streets

- Clusters of houses

- Workshops and craft areas

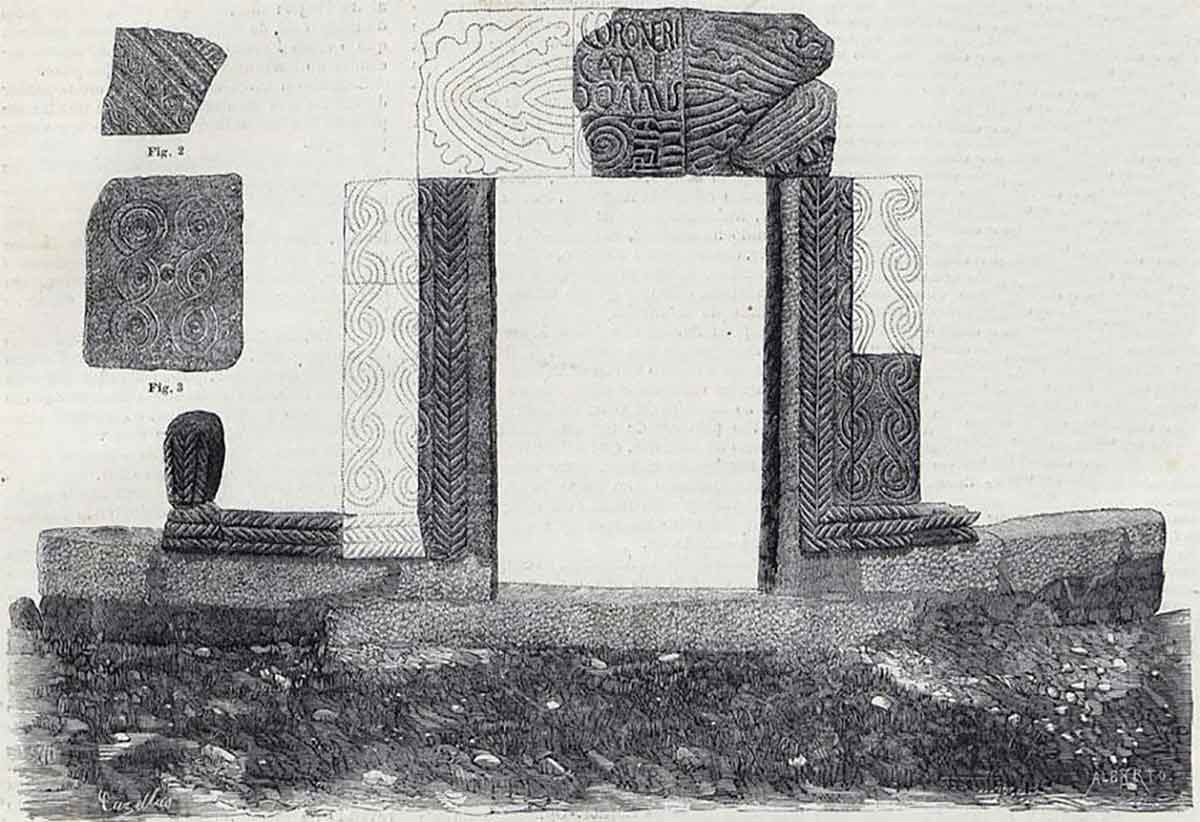

In some of these sites, an inner, elevated area formed an acropolis – a kind of “upper town” with important buildings. The largest fortified centers, known as oppida, could have:

- Concentric moats and stone walls

- Towers reinforcing the defenses

- Monumental gateways decorated with warrior sculptures

- Internal courtyards with fountains, drains, and wells

Finds from northern Portugal show strong external influences. Ceramics and metalwork bear signs of contact with Greek, Italic, and Tartessian cultures. Pottery often features patterns such as concentric circles, “double S” designs, and shield motifs.

Metal finds include:

- Tools and weapons: axes, sickles, spears, daggers

- Ornaments: fibulae (brooches), torques (neck rings), viriae (bracelets)

These objects testify to the skill of Celtic blacksmiths and their connections to wider Mediterranean networks.

From the 2nd century BCE onward, Roman expansion into Iberia changed everything. Over time, the Celtic tribes were Romanized, their forts abandoned in favor of new towns and villages in the valleys. But many of their earlier settlements remain, especially in Portugal’s north.

Where to See Celtic Portugal Today

If you want to explore Portugal’s Celtic heritage, the Minho region in the north is the ideal base. Archaeologists estimate there may once have been over 4,000 Celtic sites in this area alone.

Here are three of the most impressive and accessible.

1. Citânia de Briteiros: A Celtic City in the Clouds

Located a short drive from Guimarães, Citânia de Briteiros is one of Portugal’s largest and best-preserved Iron Age hillforts. It has been a National Monument since 1910 and is a textbook example of an advanced Celtic settlement.

What makes Briteiros so special?

- It sits at 336 meters (1,102 feet) above sea level, covering around 24 hectares. This gave its inhabitants a commanding view and quick access to the nearby river.

- Its defenses are impressive: four lines of walls, supported by ditches and adapted to the terrain. Three main concentric walls converge in the north; a fourth protects a vulnerable area on the northeast.

- Wall thickness ranged from two to three meters, with heights of around two meters.

At the heart of the settlement lies the acropolis, the main zone with:

- Residential areas

- Public baths

- The so-called “Casa do Conselho” (Council House)

The street plan is strikingly organized. A long main street runs from the southwest (near the baths) to the highest part of the settlement, with smaller side streets branching off to form something like ancient “city blocks.”

Most houses were circular, each forming part of a small family compound enclosed by a low wall. Within these compounds, different buildings had different roles:

- Round houses for living

- Rectangular buildings for storage and tools

Wealthier families lived higher up in the acropolis, in more substantial homes.

One especially notable structure is an 11-meter-wide circular building with a stone bench running inside. Due to its size and central position, it has been interpreted as the Council House, where elders gathered – or possibly a venue for feasts and communal events.

The bathhouses at Briteiros are also remarkable. Two are located outside the core residential areas:

- The southwestern bathhouse is the best preserved, with visible atrium, tanks, main chamber, and oven.

- The eastern bathhouse is larger and appears to have included stables, warehouses, and workshops.

To complete your visit, the Museu da Cultura Castreja houses a rich collection of pottery, glass, and metal finds from Citânia de Briteiros, bringing the site’s daily life into clearer focus.

2. Citânia de Sabroso: A Fortified Outpost for Elites

Just a short distance from Briteiros lies Citânia de Sabroso, another key Celtic hillfort and National Monument.

Smaller than Briteiros but no less fascinating, Sabroso consists of around 39 circular and rectangular houses enclosed within mighty walls. It dates to the second half of the first millennium BCE and sits at 270 meters (885 feet) altitude, covering about three hectares.

Sabroso’s walls are among the most monumental pre-Roman fortifications in northern Portugal:

- Two lines of sloping granite walls in a polygonal layout

- Up to four meters thick (13 feet)

- A perimeter of nearly 400 meters (1,300 feet)

- Walls reaching five meters (16 feet) in height

Two main gates, one to the north and one to the south, controlled access.

Inside, most houses are circular, with a few rectangular structures connected to a cistern. Unlike the more regular street grid at Briteiros, Sabroso’s pathways are irregular, winding around the houses.

Because of its small size, strong defenses, and strategic position, some archaeologists believe Sabroso may have been:

- An elite stronghold, reserved for local leaders

- Or a religious center, possibly supported by the discovery of a carved boulder with a cavity that might have been used as an altar

Walking through Sabroso today, you get a sense of how seriously these communities took defense, status, and ritual.

3. Cividade de Terroso: A Prosperous Atlantic Hub

Further west, near the coast at Póvoa de Varzim, lies Cividade de Terroso – once one of the most prosperous Celtic hillforts in the Iberian Peninsula.

Its location close to the ocean made it a key player in Atlantic and Mediterranean trade. During the Punic Wars, Roman commanders learned of its wealth in gold and tin, prompting Decimus Junius Brutus Callaicus to lead a campaign to conquer the region. Cividade was destroyed, rebuilt, and later thoroughly Romanized – but its Celtic roots are still visible.

Perched at 152 meters (498 feet) above sea level, Cividade de Terroso is heavily fortified, with:

- Three lines of walls surrounding the acropolis

- Walls built in different phases as the settlement grew

- Construction adapted to the hill’s contours, using large stone blocks without mortar

In its earliest phase, houses were made from clay mixed with plant material. From the 5th century BCE onward, under Phoenician influence, new building techniques appeared, including the use of iron spikes in stone construction.

Most dwellings from the pre-Roman period are circular, about 4–5 meters (13–16 feet) in diameter, with:

- Walls 30–40 centimeters (12–16 inches) thick

- Stones arranged in double rows, smooth sides facing inward and outward

- The gap between filled with smaller stones and gravel mortar for strength

Later, Roman influence brought rectangular houses with tiled (tegula) roofs and more regular street planning. Excavations have revealed:

- Funerary enclosures (unusual in Portuguese Celtic sites)

- Houses organized around central courtyards where daily life unfolded

- Two main streets and multiple building phases

Floors range from thin clay and gravel, often decorated with wavy lines or circles (especially around fireplaces), to thicker, denser surfaces in the Roman period.

To make sense of it all, visit the Núcleo Interpretativo at the site and the Museu Municipal de Póvoa de Varzim, which displays an extensive collection of artifacts from Cividade de Terroso.

Why Celtic Portugal Matters

Portugal’s Celtic heritage is easy to overlook. There are no standing stone circles like Stonehenge, and the stories of druids and heroes are less famous than those from Ireland or Wales. But in the hills of Minho and along the Atlantic coast, the traces of Celtic life are carved into stone walls, circular houses, and carefully planned streets.

Visiting sites like Citânia de Briteiros, Citânia de Sabroso, and Cividade de Terroso lets you:

- Walk through prehistoric streets

- Stand inside council houses where elders once gathered

- Look out over the same landscapes that Celtic communities defended and farmed

It’s a reminder that the Celtic world was not just an island story. It was a European story – and Portugal was very much part of it.