Ulysses S. Grant is easy to flatten into a headline: Civil War hero, corrupt president, drunk, savior of the Union—take your pick. The real man, though, was far more complicated: a quiet Ohio boy who hated his father’s tannery, stumbled through a string of failures, and then, almost against his own nature, became the hard-driving general who broke the Confederacy and steered the country through Reconstruction.

From Point Pleasant to the Plow

Grant entered the world on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio. When he was still an infant, his parents, Jesse and Hannah, moved the family to Georgetown, a small town where his childhood unfolded in a predictable rhythm of school, farm chores, and work at his father’s tannery.

He hated the tannery. The stench, the mess, the dead animal hides—none of it suited the sensitive, quiet boy. Whenever he could, he traded tanning for outdoor work and, especially, for time with horses. Grant was an exceptional horseman from a young age, calm and confident around animals in a way he rarely was around people.

By his own later account, his childhood was “uneventful.” He liked fishing and ice skating, avoided the spotlight, and developed a reputation as shy, even withdrawn. Nothing in those early years suggested he would one day command the largest armies the United States had ever fielded.

A Name Change at West Point

At seventeen, Grant still didn’t know what he wanted to do. His father made the decision for him: the army. With Jesse’s help and political connections, the skinny teenager secured a spot at the United States Military Academy at West Point.

There, a small clerical error helped create an iconic name. He arrived as Hiram Ulysses Grant, but official paperwork flipped his names and inserted his mother’s maiden name, Simpson, as his middle initial. Instead of correcting it, he let it stand. Ulysses S. Grant was born—initials that classmates joked stood for “Uncle Sam,” soon shortened simply to “Sam.”

Grant was no academic star. He graduated 21st in a class of 39, solidly middle of the pack, though he stood out in mathematics and, unsurprisingly, in horsemanship. His dream was modest: finish his required service and become a math teacher somewhere quiet. History had other plans.

War, Love, and Disappointment

West Point also gave Grant a family connection that would shape his life. His roommate, Frederick Dent, invited him to the Dent family plantation in Missouri. There, Grant met Frederick’s sister, Julia, and the two quickly fell in love.

Their families, however, were not thrilled. Jesse Grant was an abolitionist who despised slavery. The Dents owned enslaved people and doubted that a young officer with little money could adequately provide for Julia. Despite this, the couple became secretly engaged in 1844, hoping time would soften parental opposition.

Before they could marry, war intervened. The Mexican–American War broke out, and Grant went south with the 4th Infantry Regiment under General Zachary Taylor. He distinguished himself in combat, earning citations for gallantry and meritorious conduct. Still, he disliked aspects of the war and missed Julia fiercely.

They finally married in 1848, after he returned from Mexico, and eventually had four children. But peacetime did not bring Grant peace of mind. He bounced from posting to posting, often far from his family, growing more frustrated with army life.

Lonely and under pressure, Grant began drinking. Thin and small, he held his liquor poorly, and a handful of bad incidents earned him a lasting reputation for drunkenness. Business ventures he tried to fund a more stable family life failed. By 1854, facing disciplinary problems and without much enthusiasm for his duties, he resigned his commission.

Failure on the Farm

Civilian life didn’t go smoothly either. Grant tried to farm land given by Julia’s father in Missouri, but the farm never turned a profit. He sold firewood, dabbled in real estate and engineering, and took any work he could find. Nothing stuck.

By 1860, he was back where he had started as a boy: working in his father’s tannery, this time under his younger brothers. For a man with pride and military experience, it was a humbling, even humiliating, place to be.

Had history ended there, Grant might have been remembered, if at all, as another anonymous striver of the mid-19th-century Midwest—a talented rider and decent soldier who never quite found his footing.

The Civil War Calls Him Back

The Civil War changed everything. When the Union called for volunteers in 1861, Grant rejoined the army, first helping organize local regiments, then quickly earning field commands.

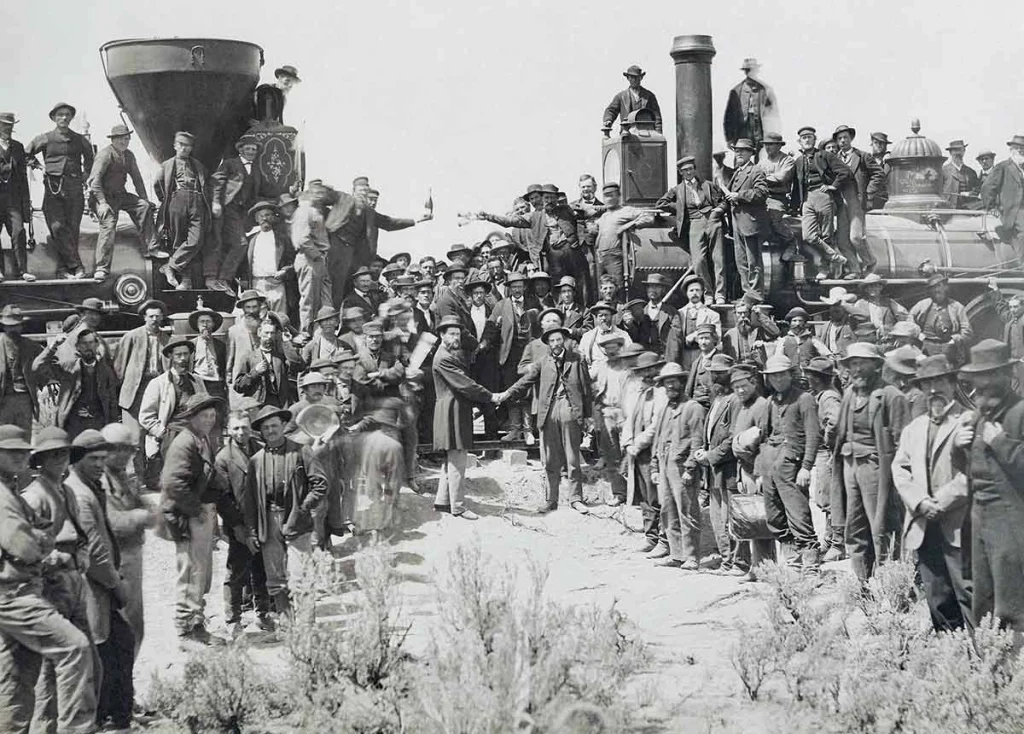

His rise was astonishingly fast. At Fort Donelson in Tennessee, he won the Union’s first major victory of the war. When the Confederate commander asked for terms, Grant replied that he would accept nothing less than “unconditional and immediate surrender.” Newspapers loved it; “Unconditional Surrender” Grant became a national hero almost overnight.

More victories followed: Shiloh, where the cost in lives shocked the country but proved Grant’s determination; Vicksburg, where his relentless siege split the Confederacy along the Mississippi River; and a grinding campaign in Virginia against Robert E. Lee.

Grant was not a flashy strategist. He was methodical, relentless, and willing to take risks. Those same qualities earned him criticism. When frontal assaults at Cold Harbor in 1864 led to nearly 13,000 Union casualties in less than two weeks, some in the North labeled him a “butcher.” Grant himself later admitted that the attack brought no advantage worth the cost.

But President Abraham Lincoln understood what he had in Grant: a commander who would fight, keep fighting, and not lose his nerve. In 1864, Lincoln promoted him to lieutenant general—the first to hold that rank since George Washington—and gave him command of all Union armies. Within a year, Lee surrendered at Appomattox.

In the public mind, Grant became the face of Union victory: the plain, mud-splattered general who had carried the country through its bloodiest trial.

General in the White House

In 1868, as the nation struggled through Reconstruction, Republicans turned almost automatically to Grant as their presidential candidate. He won, bolstered by the enthusiastic support of newly enfranchised Black voters in the first presidential election in which they could take part.

Grant brought an army mindset into the White House. He staffed his administration with former military colleagues and approached problems with a commander’s directness. His presidency was anything but calm.

He pushed hard for the Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed voting rights regardless of race, and supported efforts to protect Black citizens in the South from violent groups like the Ku Klux Klan. He backed the creation of the Civil Service Commission to reduce political patronage and presided over the establishment of the Department of Justice.

At the same time, his administration became synonymous with scandal. Grant was personally honest, but he was loyal—sometimes blindly so—to friends and allies who were not. Corruption plagued various branches of government during his tenure, tarnishing his reputation.

Another troubled area was federal policy toward Native Americans. Grant appointed Ely S. Parker, a Seneca engineer and former Civil War staff officer, as the first Native American commissioner of Indian Affairs—a groundbreaking move. Yet his broader policy leaned toward forced assimilation while the U.S. government continued to pressure and dispossess Indigenous nations across the Plains.

He served two terms, weathering economic turmoil and political attacks, then stepped aside in 1877.

More Stories

Around the World and Back to the Pen

Leaving office didn’t mean fading away. Grant embarked on a grand world tour, visiting Europe, the Middle East, and Asia with Julia at his side. Crowds greeted him like a conquering hero, and he met with kings, emperors, and prime ministers who were curious about the man who had led the United States through civil war.

Back in America, he briefly served as president of the Mexican–American Railroad company. But in 1884, bad luck and bad partners wiped out his savings in a financial scandal. For the first time in decades, the former president and general faced serious money troubles.

To provide for his family, Grant turned to writing. He produced articles and sketches about his life and then, encouraged by his friend Mark Twain, began his memoirs. By this time, heavy cigar smoking had caught up with him. Doctors diagnosed throat cancer. Writing became a race against death.

Grant pushed himself, often in great pain, to finish the book. He completed the final pages just days before he died on July 23, 1885, at age 63. His funeral in New York City drew an estimated 1.5 million mourners, and his massive tomb—Grant’s Tomb—remains the largest mausoleum in the United States.

A Flawed, Essential Figure

For a long time, popular memory treated Grant either as a near-saint who saved the Union or as a blundering drunk whose presidency was a swamp of corruption. Neither view is fair.

The Grant who emerges from his full life story is more human—and more interesting. He was a shy child who never sought glory, a young officer who doubted himself, a middle-aged man who knew the taste of failure and humiliation. He battled loneliness and alcohol, sometimes losing. He was also the steady hand the Union needed at its darkest hour, a president who, despite missteps, fought to protect the rights of formerly enslaved people, and a writer who turned his last strength into one of the finest military memoirs ever written.

Ulysses S. Grant will never fit neatly into a simple label. But if you trace his journey—from the tannery in Ohio to the parlor at Appomattox, from battlefield tents to the Oval Office—you find a man who kept getting back up, kept moving forward, and, in doing so, left a permanent mark on the United States.