Today, the Palace of Versailles is one of the most visited heritage sites on Earth. Millions of people walk through its glittering Hall of Mirrors and manicured gardens every year, most of them thinking of one man: Louis XIV, the “Sun King.”

But Versailles did not begin as a symbol of absolute power. It started as a miserable little hunting spot in a bad location.

A Palace Built in the Wrong Place

Versailles was originally just a small village in a swampy area, about 20 kilometers southwest of Paris. The land was damp, the ground was poor, and there was no major river nearby. Hardly the ideal place for a royal residence.

What it did have was game. From the late 16th century, Henri IV and his son Louis XIII loved to hunt in the woods around Versailles. In 1623, Louis XIII had a simple hunting lodge built there so he could stay close to the action. Between 1631 and 1634, this modest lodge was turned into a small brick-and-stone château. That little building was the seed from which the enormous Palace of Versailles would grow.

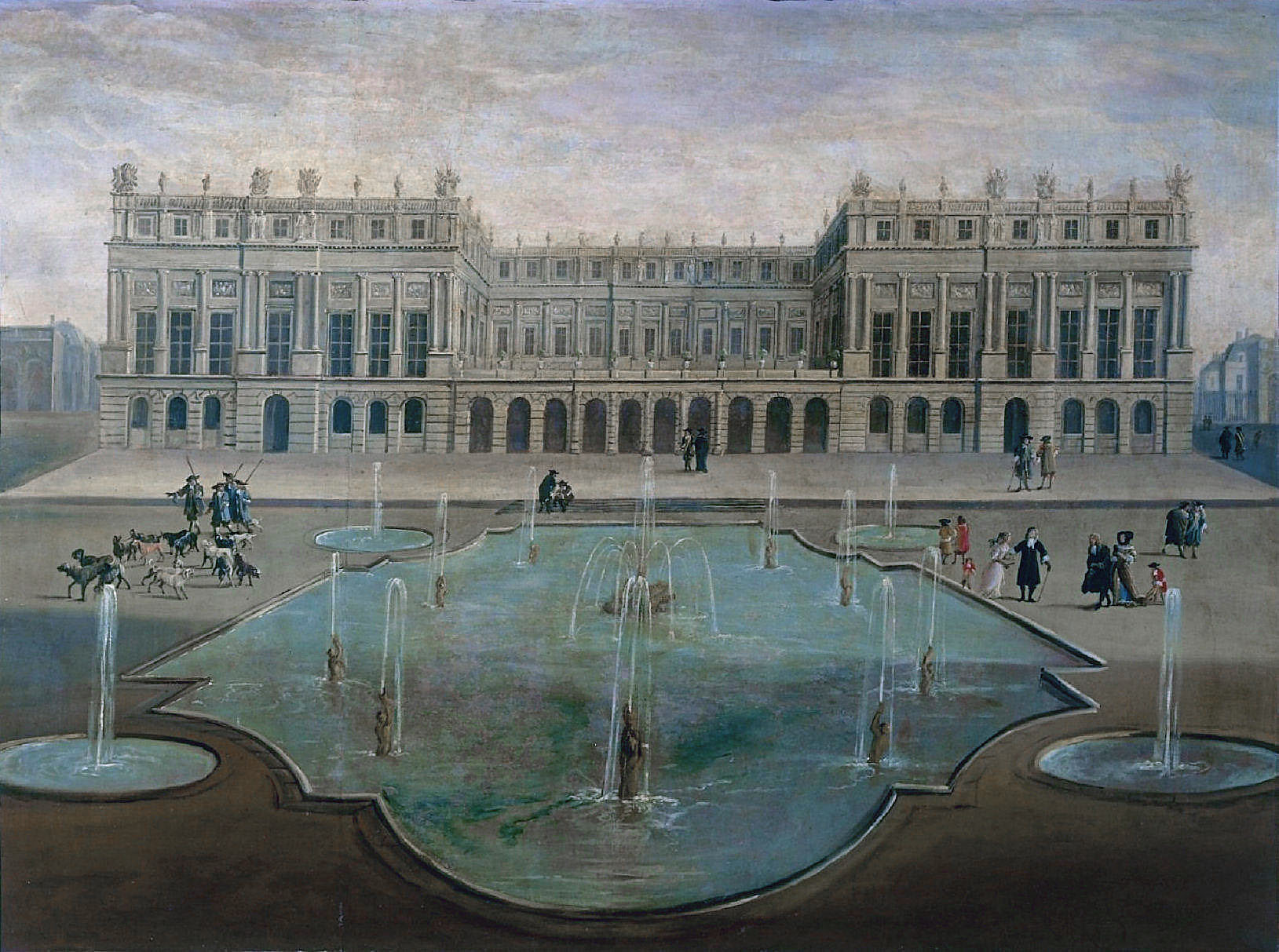

The big problem was water. The palace sits on a slight rise, while the great River Seine flows lower down toward Paris. There was no easy way to bring water up to Versailles. Yet Louis XIV wanted gardens full of fountains, basins, and water jets—1,600 of them.

André Le Nôtre, the king’s gardener, used every local water source he could find—small streams like the Gally creek—and engineers from across Europe were brought in to design complex hydraulic systems. They dug canals, built reservoirs, and invented some of the most ambitious waterworks seen since Roman times, all to make the fountains of Versailles come to life in a place that naturally had very little water.

A Political Turning Point: The “Day of the Dupes”

Versailles entered political history even before Louis XIV.

In November 1630, a dramatic power struggle played out involving Louis XIII, his mother Marie de’ Medici, and his chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu. Marie had originally brought Richelieu to court, but over time he became more powerful than she liked. Determined to get rid of him, she pressured her son to dismiss the cardinal.

On November 10, Louis XIII appeared to give in. Marie believed she had finally won. The next day, Richelieu found the doors of the Luxembourg Palace in Paris—the queen mother’s residence—closed to him. He slipped in through a secret entrance and confronted both Marie and the king.

Marie forced Louis to choose: his mother or Richelieu. At first, it looked as if she had succeeded. But the king realized he needed Richelieu to govern the kingdom effectively. The interests of France, he decided, were more important than his mother’s jealousy.

On November 11, Louis XIII left Paris for Versailles and summoned Richelieu to join him there. He restored the cardinal to favor and effectively exiled his mother from court. Marie de’ Medici left for Compiègne and never saw her son again. This episode, remembered as the “Day of the Dupes,” marked the end of her political influence—and tied Versailles to a decisive moment in royal power.

Louis XIV and the Golden Age of Versailles

Louis XIII may have planted the seed, but it was his son Louis XIV who made Versailles famous.

As a young king, Louis XIV came to Versailles mainly for hunting, accompanied by his mother Anne of Austria and his brother Philippe, Duke of Orléans. At first he saw it as just another country retreat. But after 1661, he decided to turn it into something far greater: a palace that would embody his power and the idea of absolute monarchy.

In the 17th century, France was rising as the leading power in Europe. Louis XIV ruled as a king “by divine right”—in his view, he held all authority from God. With his minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, he reformed the royal academies and used art, architecture, and spectacle to glorify the monarchy.

Versailles became the stage on which this power was displayed. Between 1661 and the early 1680s, the old hunting château of Louis XIII was gradually swallowed up and transformed into a vast palace with endless wings, courtyards, and gardens. The court began spending more and more time there, and in 1682, Louis XIV made Versailles the official residence of the king and the seat of government.

From then on, to be at Versailles was to be close to power. To be absent from Versailles was to risk being forgotten.

The Creators Behind the Masterpiece

Versailles was not the work of a single man. It was the result of a team of exceptional artists and architects serving one king and one vision.

- Louis Le Vau – As First Architect to the King, he led the first major expansion in 1668. He kept Louis XIII’s old château as the core and wrapped it inside a new envelope of stone—the “Le Vau envelope”—adding state apartments for the king and queen.

- Jules Hardouin-Mansart – The leading architect of the later part of Louis XIV’s reign, he directed the second great building phase between 1678 and 1689. He expanded the palace and created some of its most iconic spaces:

- The Hall of Mirrors

- The Orangery

- The Royal Stables

- The Royal Chapel

- Charles Le Brun – As “First Painter to the King,” Le Brun designed the interiors and coordinated the decoration of Versailles. With Colbert’s backing, he reshaped the Academy of Painting and Sculpture and set a style that influenced all of Europe. His work is visible in the Hall of Mirrors, the War Room, the Peace Room, and the king’s state apartments. He even designed the famous Ambassadors’ Staircase (sadly demolished in 1752).

- André Le Nôtre – The genius behind the gardens, Le Nôtre created the classic “French garden” look: strict geometry, long perspectives, terraces, fountains, and carefully trimmed greenery. His design turned the landscape around Versailles into a controlled, theatrical extension of the palace itself.

Together, these men turned a modest lodge into a total work of art: architecture, painting, sculpture, water, and greenery all working to magnify the king.

The Sun King and His Symbol

Louis XIV crafted his image carefully. He chose Apollo—the Greek god of the sun, music, and the arts—as his symbolic twin. From this came his famous nickname: le Roi Soleil, the Sun King.

At Versailles, this symbolism is everywhere. The decor is full of:

- Suns

- Laurel wreaths

- Lyres

- Chariots and bows

The idea was simple: just as the sun is the center of the solar system, the king was the center of the kingdom. The palace and its gardens were designed to make visitors feel that they were moving through a universe organized around Louis XIV.

Hall of Mirrors and Gardens: A Stage for Spectacle

If there is one room everyone remembers, it is the Hall of Mirrors.

Built between 1678 and 1684 by Hardouin-Mansart and decorated by Le Brun, this 73-meter-long gallery is lined with 357 mirrors facing large windows that look out over the gardens. In an age when mirrors were extremely expensive, this was an open display of wealth and technical skill.

The Hall of Mirrors was not just for show—it was a place for royal ceremonies, receptions, and dazzling parties.

Outside, Le Nôtre’s gardens were no less theatrical. They featured:

- 43 kilometers of paths

- 155 statues

- Fountains, groves, and water basins arranged like outdoor stages

In the spring of 1664, Louis XIV hosted his first great festival there: Les Plaisirs de l’Île Enchantée (“The Pleasures of the Enchanted Island”). He invited 600 guests, commissioned a ballet from Molière and Lully, and even danced himself in the performance.

Louis XIV was a talented dancer and loved to perform. These parties, held in the Hall of Mirrors and the illuminated gardens, were not just entertainment—they were carefully choreographed displays of royal power.

A Model for Europe

Versailles quickly became the ultimate symbol of absolute monarchy.

From around 1690 onward, rulers across Europe tried to imitate it. Palaces such as:

- The Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso in Spain

- Peterhof Palace near Saint Petersburg in Russia

were directly inspired by Versailles. They copied its grand facades, wide staircases, formal gardens, and lavish decoration. But despite all efforts, no other palace quite matched the scale and impact of the original.

The cost and effort were immense. By 1685, around 36,000 workers were employed permanently at Versailles. Building the king’s dream required an army of masons, gardeners, sculptors, painters, and craftsmen.

From Royal Residence to National Museum

After the French Revolution, the fate of Versailles was uncertain. The monarchy fell, many furnishings were sold, and the palace was partly neglected.

In 1837, King Louis-Philippe gave Versailles a new purpose by creating a museum inside the palace dedicated to “all the glories of France.” The focus shifted from royal life to national history.

Real restoration came in the 20th century. By the 1920s, the palace was in serious disrepair, and money was scarce. In 1924, American philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. offered financial support to help save Versailles. His funding aided major restoration efforts, allowed parts of the gardens to reopen, and even brought some original pieces of furniture back to the palace.

Versailles Today

Now, the Palace of Versailles is a museum and a global icon. It welcomes around 10 million visitors every year.

Guests can:

- Wander through the grand rooms, including the King’s State Apartments and the Hall of Mirrors

- Explore the vast gardens and their fountains

- Discover a collection of about 60,000 artworks telling the story of French history

From a swampy hunting ground to the glittering heart of a kingdom, from royal residence to world heritage site, Versailles has constantly reinvented itself. What has never changed is its power to impress—and to remind visitors how architecture, art, and politics can come together in one extraordinary place.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Royal Family Blood-Marriages in Ancient Egypt

5 Legendary Kings Who Built Thailand: From Sukhothai to the Chakri Dynasty

America’s Most Beloved Urban Parks

War of 1812: Winners, Losers, and Lasting Effects

Mexico’s Ancestral Farming Practices: Milpa, Chinampas & Terraces

The Nuremberg Rally: Power and Propaganda in Nazi Germany

4 Small Greek Cities That Shaped History

Roman Voyages to Indo-Parthian India

How Tobacco and Sweet Potatoes Shaped China

John Marshall: The Justice Who Defined the Supreme Court

Four Great Cities of the Americas Before Columbus

Sintra: A Fairy-Tale Town Steeped in History