When the War of 1812 finally ended in late 1814, it looked, on the surface, like a pointless struggle. After more than two years of fighting from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, the Treaty of Ghent simply put things back the way they had been. No territory changed hands. No grand, dramatic surrender reshaped the map.

Yet beneath that calm surface, the war had quietly reshaped North America. The United States walked away with a stronger sense of identity and a more confident place in the world. Britain stabilized its empire and began building a partnership with its former colony. And Native American nations, who had fought and died on both sides, paid the heaviest price of all.

A Peace That Fixed Little — But Changed a Lot

The Treaty of Ghent, signed on December 24, 1814, formally ended hostilities between the United States and Britain. Both sides agreed to return captured territory, exchange prisoners of war, and set up joint commissions to resolve border disputes, especially in the Great Lakes and Niagara regions.

Curiously, the treaty did not address the issues that had supposedly justified the war in the first place. There was no clear resolution on British impressment of American sailors or interference with American trade with France. Those grievances had helped fuel calls for war, yet they disappeared from the text of the peace agreement.

One clause that did appear—at least on paper—was a promise to restore Native American lands taken during the conflict. In reality, American political and military leaders ignored this obligation. The commitment to Native land rights looked good in diplomatic language, but it had no force in American policy once the fighting stopped.

As had happened after the American Revolution, the treaty’s gaps had to be filled by later negotiations. The Rush–Bagot Agreement of 1817 limited naval armaments on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, calming one of the most sensitive regions along the border. The Convention of 1818 then clarified the line between the United States and British Canada and helped create a more stable, long-term frontier.

The guns fell silent with Ghent, but the work of building a lasting peace unfolded step by step in the years that followed.

From War-Strained Republic to “Era of Good Feelings”

Politically, the War of 1812 nearly broke the United States but ended up solidifying it.

Before the war, the Federalist Party had opposed fighting Britain. Associated with men like John Adams, John Jay, and Alexander Hamilton, the Federalists favored close economic ties with Britain and a strong central government. During the war, they became increasingly outspoken in their criticism, and their opposition culminated in the Hartford Convention of 1814, which many Americans later viewed as disloyal during a time of national crisis.

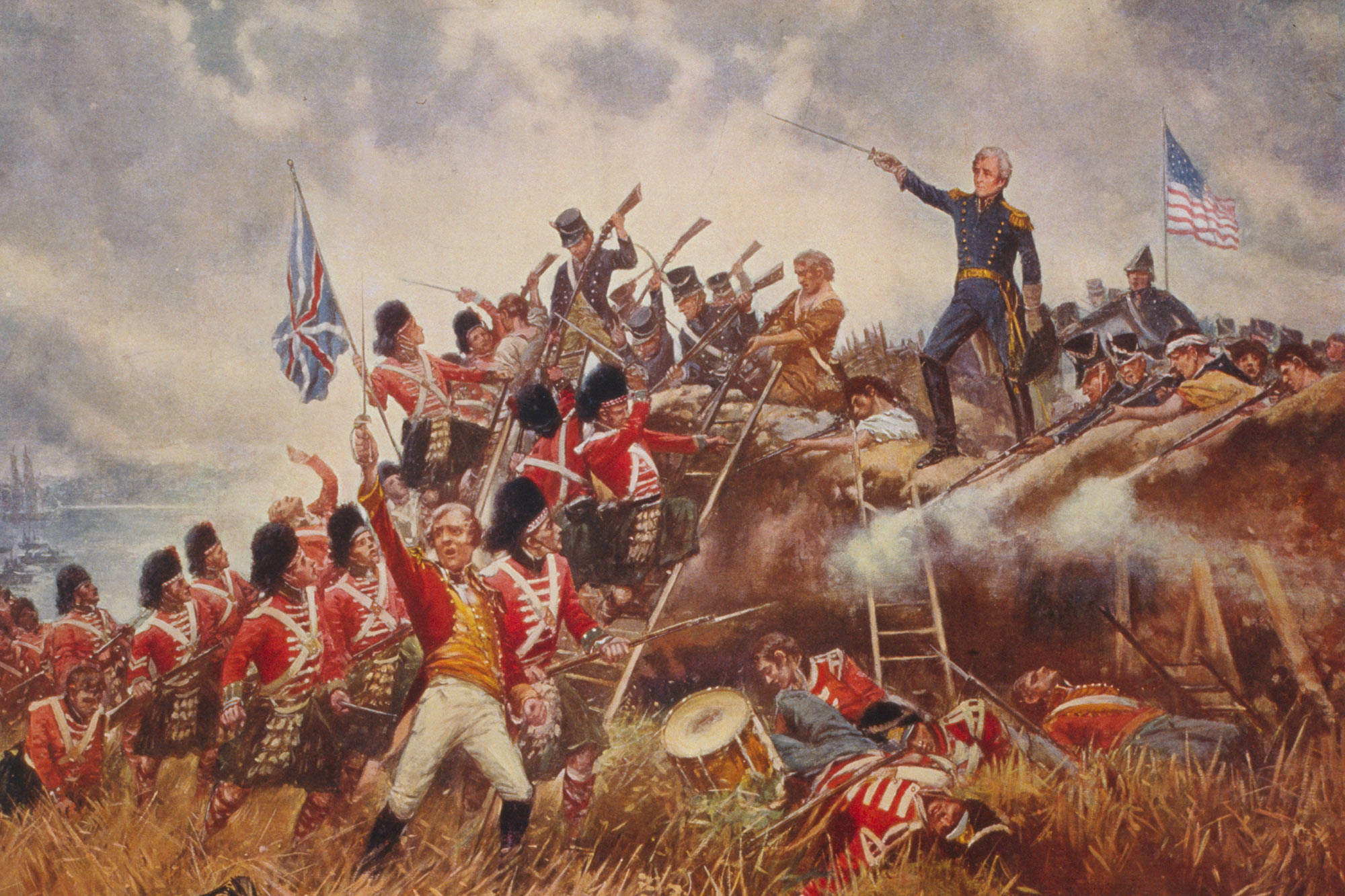

When the war ended without disaster for the United States—and even with some glorious moments, such as the defense of Baltimore and the American victory at New Orleans—the Federalists’ stance looked like a political miscalculation. Their reputation never recovered. Within a few years, the party had effectively collapsed.

This left the Democratic-Republicans dominant on the national stage. The reduction in open party conflict led to what later historians called the “Era of Good Feelings”—a period in the 1810s and 1820s marked by a sense of unity and optimism. Ironically, with the Federalists gone, the Democratic-Republicans quietly adopted several of their ideas, including protective tariffs and federal support for infrastructure. The party that had once resisted a strong central role in economic development now embraced it in practice.

The war also encouraged a more assertive American foreign policy. In 1823, President James Monroe announced the Monroe Doctrine, warning European powers not to attempt to restore or expand their colonial holdings in the Americas. The United States still lacked the military power to enforce such a doctrine alone, but its increasingly friendly relationship with Britain meant it could count on the Royal Navy’s interest in keeping rival empires out of the Western Hemisphere.

Territorially, the United States continued to grow. The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819 secured Florida from Spain. The earlier Louisiana Purchase and Lewis and Clark’s expedition had already opened vast lands in the west to American imagination and ambition. The War of 1812 weakened British influence and some Native American resistance, but it did not magically erase tribal claims. Instead, it set the stage for a long, grinding struggle over land.

Economic Shock and the Drive to Build

Economically, the war hit the United States hard. The British blockade severely disrupted trade, strangling exports and imports alike. Farmers suffered from falling markets, merchants were cut off from foreign partners, and shortages drove up prices. By 1815, the cost of many goods and services had risen roughly thirty percent compared to prewar levels.

The British attack on Washington, D.C., in 1814—culminating in the burning of government buildings—was not just a symbolic humiliation. It exposed how vulnerable the American capital and infrastructure truly were. The federal government hovered near bankruptcy.

Yet the end of the war, combined with the end of the Napoleonic Wars, brought sudden relief. Trade routes reopened. The Royal Navy no longer needed to seize sailors to fill its ships, and impressment faded away without any dramatic declaration. American merchants and farmers quickly returned to the Atlantic marketplace.

Despite this recovery, the war experience left a lasting mark on American thinking. Economic uncertainty and population growth pushed many families westward, searching for fresh land and better prospects. Figures like Davy Crockett became symbols of this restless migration, representing the promise—and myth—of the American frontier.

The destruction and chaos of the war also convinced policymakers that the country needed better internal connections. In the following decades, the United States invested heavily in canals, roads, and eventually railroads. Industry grew as iron and steel production expanded, textile mills spread, and factory-based manufacturing took root. In this way, a war that had exposed the young nation’s weaknesses helped to accelerate its transformation into a more modern, economically complex society.

Britain: A Peripheral War, a Strategic Peace

From Britain’s perspective, the War of 1812 was never the central struggle of the era. The British government’s main concern was Napoleon Bonaparte and the shifting battlefield of Europe. The war in North America was important, but secondary.

For that reason, British defeats at Lake Erie or New Orleans, while embarrassing, did not carry the same weight as campaigns in Spain or the final showdown at Waterloo. When negotiators in Ghent agreed to restore the prewar borders, British leaders considered it an acceptable and even favorable outcome. The agreement allowed London to redeploy ships and troops where they mattered most: Europe.

British North America, however, did not emerge unchanged. The war made clear that the United States was a permanent and ambitious neighbor. While Canada remained intact, British authorities recognized the need to strengthen defenses and maintain a stable, clearly defined border to discourage future American adventurism.

Economically, Britain also suffered from the strain of fighting on multiple fronts. National debt ballooned, and trade was disrupted across oceans and continents. Yet, after 1815, Britain entered a period of rapid industrial expansion and imperial consolidation. The war with the United States, resolved without a humiliating loss, cleared the way for a gradual rapprochement with its former colony.

Over the 19th and 20th centuries, this evolving relationship grew into the Anglo–American partnership, culminating in close cooperation during both world wars and continuing as a crucial alliance into the present.

Native American Nations: The Biggest Losers

When historians ask who “won” the War of 1812, they can point to achievements on both the American and British sides. But if the question is who lost the most, the answer is tragically straightforward: Native American tribes.

Before and during the war, many Native nations had tried to build coalitions strong enough to resist U.S. expansion. The most famous of these was Tecumseh’s Confederacy, which sought to unite tribes across the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes. Its defeat at Tippecanoe and the Battle of the Thames, where Tecumseh was killed in 1813, shattered this vision. Without his leadership and the broader alliance, Native groups were left fragmented and weakened.

The Treaty of Ghent’s promise to restore Native lands was never honored in the United States. Instead, the postwar period saw a rapid acceleration of land cessions, often imposed at gunpoint or under severe pressure. In 1814, after Andrew Jackson’s victory over the Creek at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the Treaty of Fort Jackson forced the Creek to surrender more than twenty million acres of land. In 1817, the Treaty of Fort Meigs pried more land from the Shawnee and Wyandot.

Crucially, even tribes that had fought alongside the United States were not shielded from dispossession. Loyalty in wartime did not translate into long-term security. As white settlers poured west, Native communities were pushed further to the margins.

By 1830, this logic culminated in the Indian Removal Act, signed by President Andrew Jackson. Over the next two decades, this policy led to the forced relocation of tens of thousands of Native people from their homelands east of the Mississippi River to designated lands in what is now Oklahoma. The Trail of Tears—the deadly forced march endured by the Cherokee and shared, in similar form, by the Choctaw, Creek, and others—was one of the most direct and devastating consequences of the post–War of 1812 era.

The war, in short, weakened Native alliances, removed critical British support, and opened a wide path for American expansion at their expense.

A War with Two Victors and One Great Tragedy

The War of 1812 left a mixed legacy across the Atlantic world.

For the United States, it strengthened national identity, encouraged economic growth, and helped shift the country onto a more assertive diplomatic path. The story of the bombardment of Fort McHenry and the sight of the flag still flying at dawn inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem that became “The Star-Spangled Banner,” later adopted as the national anthem in 1931. The war also forced Americans to confront their own weaknesses, and in doing so, pushed them to build stronger institutions, better infrastructure, and a more robust economy.

For Britain, the conflict ended in a pragmatic, strategically useful peace. By removing a potential front of future conflict with the United States and clarifying key borders, London could focus on its struggles in Europe and the broader work of managing a global empire. Over time, the former enemies became partners, fighting side by side in two world wars and building a modern alliance that remains one of the most important in international politics.

For Native American nations, however, the war was a turning point in the worst sense. It shattered confederacies, stripped away allies, and undermined any remaining hope that European powers would act as a check on American land hunger. In the wake of the war, dispossession accelerated, culminating in forced removals and generational trauma that echo into the present.

If we judge the War of 1812 purely by national interests, we can say that both the United States and Britain ultimately “won.” But if we widen the lens to include the Indigenous peoples of North America, the story looks very different. The peace at Ghent may have ended the fighting between empires, but it opened the door to a new, relentless phase of expansion in which Native Americans were the ones who truly lost.