When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, Irish immigrants were among the most hated groups in the United States. They were poor, Catholic, often Gaelic-speaking, and stereotyped as violent drunks. Yet tens of thousands of Irishmen volunteered to fight—and die—for their adopted country, especially in the famous Irish Brigades on both sides of the conflict.

Why would a despised, marginalized community step forward so eagerly to fight in someone else’s war?

The answer lies in a long tradition of Irish soldiering abroad, hard realities in 19th-century America, and a very modern mix of identity, ambition, gratitude, and nationalism.

A Long Tradition of Fighting Under Foreign Flags

The Irish Brigade in Union service was not a new phenomenon. Irishmen had been hiring out their swords on foreign battlefields for centuries.

- In the Middle Ages, Hiberno-Norman lords brought Irish troops with them into France to fight for the English crown.

- As English control of Ireland tightened in the 16th century, more Irish soldiers fled to continental Europe. Spain had enough exiles to form an Irish Brigade by 1587, and Irish regiments continued to appear in European armies well into the 18th century.

- After the Williamite War in Ireland (late 1600s), thousands of Irish soldiers went to France, where the Irish Brigade fought in French service and even took part in the Jacobite Rebellions in Scotland. Irish officers also served in the Habsburg, Prussian, and Russian armies.

When Britain finally relaxed its restrictions on Catholic enlistment in the 19th century, many Irishmen joined the British Army as well. Soldiering abroad had become a familiar path for ambitious or desperate Irishmen.

Even in America, this pattern continued. During the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), harsh treatment, anti-Catholic prejudice, and sympathy for Catholic Mexico led hundreds of Irish soldiers to desert from the U.S. Army and join the Mexican side. They formed the famous Saint Patrick’s Battalion (San Patricios).

So when the Civil War began, fighting for a foreign flag was not, in itself, strange for Irishmen. It was almost traditional.

Thomas Francis Meagher: Rebel, Exile, and Union General

The most famous leader of the Union’s Irish Brigade, Thomas Francis Meagher, embodied many of these themes.

Meagher had been a passionate Irish nationalist and a leader in the failed 1848 Young Ireland rebellion. He was arrested and originally sentenced to death, but international outcry softened his punishment to transportation to Australia. He escaped in 1852 and eventually made his way to the United States, where he reinvented himself as a lawyer, journalist, and public speaker.

Personally, Meagher had some sympathy for the Confederacy, but he never forgot that America had given him asylum and a new life. For him, loyalty to the Union came first. In New York he joined the 69th Infantry Regiment, the “Fighting 69th,” as a captain despite having no formal military background. After his commanding officer Michael Corcoran was captured at Bull Run, Meagher was promoted to colonel and returned to New York to raise a larger, all-Irish formation: the Irish Brigade, formally authorized in September 1861.

Meagher had two key motives:

- Improve the status of the Irish in America

Irish immigrants were scorned and feared. Meagher believed that fighting bravely for the Union would prove their loyalty and help the Irish earn respect, political leverage, and a secure place in American society. - Train future Irish revolutionaries

Quietly, Meagher also saw the war as a military school. He hoped that Irishmen hardened in the Civil War would one day return home and use what they’d learned to fight for Irish independence.

In other words, enlistment was not just about America. It was also, in Meagher’s mind, an investment in Ireland’s future.

Why Ordinary Irish Immigrants Enlisted

Meagher’s vision set the tone, but thousands of ordinary Irish immigrants brought their own reasons to the recruiting office. For many, motivations overlapped:

- A chance to belong

In a society that mocked and distrusted them, military service offered a way to prove they were good Americans. Fighting under the U.S. flag could rewrite the story of the Irish from drunken rabble to courageous patriots. - Pride and tradition

Coming from a people with a long record of soldiering abroad, joining the Irish Brigade fit into a familiar role: the Irish warrior fighting on foreign soil, often for a cause he hoped would also somehow benefit Ireland. - Economic need

Many Irish immigrants were desperately poor. Army pay, bounties, and the promise of regular food and clothing made military service attractive, despite the risk. - Leadership and community pressure

With charismatic nationalist figures like Meagher leading recruitment and the creation of explicitly Irish units, enlistment became wrapped up with honor, pride, and community expectation. - A belief in the cause

Not all Irishmen shared the same politics, but many Union Irish—especially those shaped by British rule—felt instinctive sympathy for a strong central government over secession, or hostility toward slavery after their own history of oppression.

All these factors combined to make the Irish Brigade one of the most heavily Irish, and most determined, formations in the Union Army.

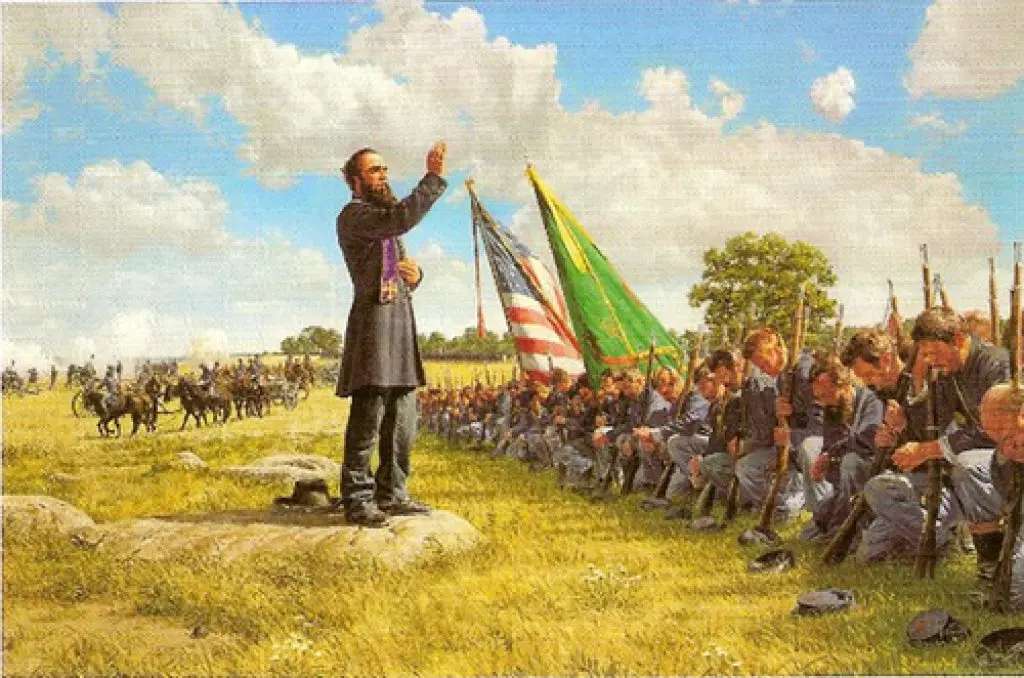

The Irish Brigade in Battle: Reputation Earned in Blood

The core of the Irish Brigade was made up of three New York regiments—the 63rd, 69th, and 88th New York—later joined by the 28th Massachusetts and 116th Pennsylvania, both with strong Irish character. For a time, the Brigade also included the 29th Massachusetts, a very un-Irish, self-described Yankee unit. Meagher jokingly called them “Irishmen in disguise,” and although they refused an Irish flag he offered, he respected their courage on the field.

The Brigade quickly gained a reputation for toughness and determination, but at a terrible cost:

- At Antietam (September 1862), the Irish Brigade advanced again and again into a storm of Confederate fire at the Sunken Road—later known as “Bloody Lane”—until they were finally ordered to withdraw.

- At Fredericksburg (December 1862), they marched straight into murderous volleys from Confederates entrenched on high ground. Their old smoothbore muskets had shorter range and poorer accuracy than the rifles used against them, forcing them to get dangerously close before they could even fire back.

- At Chancellorsville (May 1863), they took heavy losses yet again, rounding out a trio of brutal engagements that hollowed out their ranks.

At Fredericksburg alone, nearly 600 of the 1,200 Irish Brigade soldiers became casualties. Meagher begged to be allowed to recruit new men to fill the depleted units, but his requests were turned down. After more refusals, he resigned in frustration and was reassigned to the western theater. Command passed to another Irishman, Patrick Kelly.

By the time of Gettysburg in July 1863, the once-formidable Brigade could muster only about 600 men—less than a full regiment. They fought bravely again, attacking Confederate positions in the Wheatfield and taking Stoney Hill, only to be driven back with more than a third of their men dead.

In later battles, commanders came and went, many dying in action—Richard Byrnes at Cold Harbor, Patrick Kelly at Petersburg. Eventually, the U.S. Army disbanded the original Irish Brigade and merged its survivors into other units. A second “Irish Brigade” was later formed, but its Irish identity was much more diluted, and it too was disbanded in 1865, after the war ended.

Only two other infantry brigades in the entire Union Army suffered higher losses than the Irish Brigade.

More Stories

Irish in Gray: Fighting for the Confederacy

Although foreign-born soldiers were more numerous in the Union, the Confederacy also had its share of Irishmen.

There was never a formal Confederate “Irish Brigade,” but several units had strong Irish representation:

- The 1st Battalion Virginian Regulars was popularly known as the Irish Battalion.

- The Louisiana Tigers included many Irish soldiers and quickly earned a reputation for hard drinking, brawling—and fierce combat performance.

Politics split Irish nationalists as well. Meagher’s close friend John Mitchel, another veteran Irish rebel, had settled in the American South and chose to support the Confederacy out of loyalty to his new home. He and three of his sons fought in gray, while Meagher fought for the Union. Their friendship eventually shattered over the issue of slavery.

Irishmen, in other words, fought on both sides, driven by different local loyalties and interpretations of freedom, duty, and identity.

From the Civil War to the Fight for Ireland

For some Irish soldiers, the end of the Civil War was simply the end of their military careers. For others, it was only a pause between wars.

Many veterans of the Irish Brigade were drawn to the Fenian Brotherhood, a revolutionary organization committed to Irish independence. They saw themselves as following Meagher’s original idea: using skills learned in America to free Ireland.

- In 1867, Fenians tried to ship arms to Ireland for a rising, but British intelligence and poor planning ruined the effort.

- Between 1866 and 1871, Fenians launched several raids into Canada from U.S. soil, hoping to put pressure on Britain by attacking one of its colonies.

At the Battle of Ridgeway (1866), former Union and former Confederate soldiers—Irish veterans who had fought on opposite sides in the Civil War—now fought side by side against Canadian militia. They won some tactical victories, but were usually forced to retreat when British regulars and larger Canadian forces arrived. American authorities eventually cracked down, arresting conspirators and seizing weapons.

The dream of marching directly from Civil War battlefields to Irish independence did not come true, but it shows how deeply many Irish soldiers linked their American service to their national cause.

A Hard-Won Legacy

Today, the legacy of the Civil War Irish Brigade lives on in the “Fighting 69th”, which still serves as a unit of the New York National Guard. During the war itself, even hostile observers found themselves respecting the Irish.

The British war correspondent George Townsend summed it up memorably:

“When anything absurd, forlorn, or desperate was to be attempted, the Irish Brigade was called upon.”

So what motivated Irish immigrants to enlist in the American Civil War?

- A centuries-old tradition of soldiering abroad

- The hope of earning respect and acceptance in a hostile society

- The chance for pay, food, and a steady role in a time of poverty

- Charismatic leaders like Meagher, who framed service as both gratitude to America and training for future Irish freedom

- A desire to prove courage and honor—to themselves, to their community, and to their new country

They fought for America, for Ireland, for their regiments, and for their own survival. And in doing so, they carved a place for the Irish in the story of the United States, written in courage—and in staggering loss.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

From Jōmon to Yayoi: Japan Shifted from Foragers to Rice Farmers

Royal Family Blood-Marriages in Ancient Egypt

Study a Philosophy: What and How It Is

The Dark History of Witchcraft and the Devil in Medieval Europe

War of 1812: Winners, Losers, and Lasting Effects

Prague: The Habsburg Jewel of the Renaissance

Livia Augusta—First Roman Empress

A Review of Thomas Pakenham’s The Tree Hunters

A Life Pointed to God: Oswald Chambers in Plain Words

Medieval Doctors and the Black Death: How They Fought Against Plague

Versailles: From Hunting Lodge to World Icon

Finding Real Ithaca, Odysseus’s Home