In the long shadow of a turbulent century, a man from a minor noble line stepped out of rumor and into history. We remember William Wallace as the kilted thunderbolt of legend—the brave heart who roared at tyranny and paid for it with a martyr’s death. Yet the more gripping story isn’t only what he fought against, but how he fought: the strategies he shaped, the instincts he trusted, and the lessons he left behind for those who finished the work. If Scotland learned to resist a conquering empire, it’s because Wallace first taught her where to stand, when to strike, and when to fade into the heather.

This is the story of how William Wallace, man and myth alike, saved Scotland—not with a single victory or a final breath, but by remaking the terms of the fight itself.

The Man Behind the Legend

History gives us a handful of solid stones and a whole wall of legend. Wallace was probably born around 1270, not into the gilded ranks of Scotland’s greatest houses but to the middling world of minor nobility. His seal, later affixed to a letter to the German port of Lübeck, named him “William, son of Alan Wallace,” and shows a drawn bow—an emblem that hints at a life already shaped by arms long before his name flew across the glens.

And yes—the sword in the monument, the tales embroidered by “Blind Harry,” the melodrama of Braveheart—much of this is folklore layered upon a life that left too few footprints. But therein lies his magnetic pull: the facts are bare enough to demand imagination, while the deeds we can verify are fierce enough to deserve it.

Wallace’s world had been unsettled since 1292, when England’s Edward I inserted himself into Scottish succession and crowned John Balliol with one hand while shackling him with the other. When Scotland balked, Edward invaded, garrisoned towns, installed officials, and bled the land for coin. Resentment smoldered, then burned.

And somewhere amid those rising flames, Wallace stepped forward.

More Stories

Sparks at Lanark

In May 1297, a confrontation in the market town of Lanark with the English sheriff, William Heselrig, lit the fuse. By day’s end, Heselrig was dead and the garrison butchered in a midnight strike. That swift escalation—an insult, a clash, and then an organized ambush—betrays a leader whose mind already ran to war: men gathered quickly, roles assigned, timing held. The legend talks of vengeance; the record whispers of tactics.

Scotland’s elite fought their battles on horseback in glittering harness, but the land’s lifeblood was a different breed: lean, tough, mobile fighters who could ghost over moor and bog, and strike from hedgerow and hill. Wallace marshaled them into something closer to a doctrine. Rather than face superior numbers in open fields, he turned Scotland’s broken country into a weapon—harrying patrols, cutting supplies, and forcing garrisons to cower behind their own gates.

Guerrilla war wasn’t new to Scotland; Wallace made it national.

A Northern Twin

Wallace wasn’t alone. In the Highlands, Andrew of Moray raised the North in parallel, like a second flame lifting from the dark. While noble allegiances blew like weathercocks—some bending to Edward, some to Balliol, some to whoever held the purse or the sword—Wallace and Moray moved with clarity. Their aim was independence; their method was attrition.

Crucially, their campaigns sharpened a habit that would define the war: choose the ground. Trouble the enemy where he is heavy and you are light; refuse him where he is strong; force him to cross rivers and marsh, and then pounce.

That logic reached its purest expression on a late summer morning at Stirling.

Stirling Bridge: The Masterstroke

September 11, 1297. The River Forth runs like a steel band across the waist of Scotland, its crossings few and precious. The English governors of Scotland marched north to break the rebellion—and found Wallace and Moray waiting near Stirling Bridge. Waiting, and watching.

When the English began their crossing, Wallace and Moray held their nerve. A contingent made it over—enough to tempt confidence, not enough to ensure support. Then, with the enemy half-committed, the Scots struck. The bridge became a choke point; the river a trap. English cavalry, crowding and jostling, found no room to run down infantry that had learned a new language of war: the schiltron, a close-packed hedge of spears that snarled at the horse and bristled at the bow. Meanwhile, Scottish nobles on the flanks turned on English baggage and reserves, either from fresh patriotism or old opportunism. In the crush, English formations shattered. Many were cut down; more drowned in the Forth.

Stirling Bridge wasn’t just a win—it was a demonstration. Scotland could choose the when and where; she could sicken a larger force with patience and then destroy it with precision. In an instant, Wallace and Moray converted rumor into proof. The rebellion became a campaign. The campaign became a claim on government.

Guardian of Scotland

After Stirling, Wallace and Moray were appointed Guardians of Scotland in the exiled King John Balliol’s name. Moray, mortally wounded from the battle’s aftermath, died that autumn; Wallace carried on alone.

The transformation from raider to ruler is always dangerous. Wallace had to reknit a battered administration, re-open trade, and keep fractious lords inside the tent. Yet his very origins helped: he wasn’t one of the great houses, tainted by their quarrels and compromises. To common folk he was kin; to nobles he was, for a time, neutral.

He also took the war south. Wallace harried across the border into northern England, not to hold ground but to hold cash—plunder to pay men, supplies to feed them, and a message to Edward I that the fight would not be contained.

But no rebel’s success goes unanswered. In 1298, Edward came north in person.

Falkirk: When the King Arrives

Edward I, seasoned and relentless, brought a massive host and iron discipline. Wallace, recognizing the mismatch, fell back, scorching the earth ahead of the invaders. Deny forage, exhaust the supply train, let hunger do the work—that was the plan.

Fate blinked. Edward found Wallace near Falkirk on July 22. There the Scots formed three great schiltrons on rough ground, braced by archers and a slim screen of cavalry. The early fight was bitter. English horse crashed in and recoiled, meeting spear forest and mud. For an exhale of time, it looked like Stirling reversed.

But where Stirling had been a chosen ambush, Falkirk was a compelled stand. English cavalry eventually swept aside Scotland’s smaller mounted force and harried the archers. With the supports gone, Edward brought up his infantry and famed Welsh longbowmen. The schiltrons, immovable by design, could not advance without cavalry cover and could not disperse without dying. So they stood—and were riddled. Brave as granite and just as stationary, they bled until they broke.

Wallace’s reputation took the wound as deeply as his army. He resigned the Guardianship. The chorus of hindsight often blames him for failing to charge, but it mistakes constraint for choice. The truth is simple and harsh: against the full machine of Edward’s army, Wallace lacked the arms to maneuver and had almost succeeded in avoiding battle entirely. Almost.

The Lost Years

What do you do when the one thing people believe about you—winning fights—has stopped happening? If you are William Wallace, you refuse to vanish. He moved through Europe in search of leverage, appealing at the French court and angling, perhaps, for a papal audience. Diplomatic traffic has its own rhythm—letters, proxies, delays—and Wallace learned to play it just well enough to matter. At minimum, he helped stiffen French pressure on Edward and forced the English king to think twice about throwing every spear he had at Scotland all at once.

By 1303, truce with France in hand, Edward surged back with method and money. Scottish resistance crumpled in pieces. Most leaders bent the knee on terms that were, for the time, surprisingly humane.

Edward offered no terms to Wallace.

Capture, Trial, and the Making of a Martyr

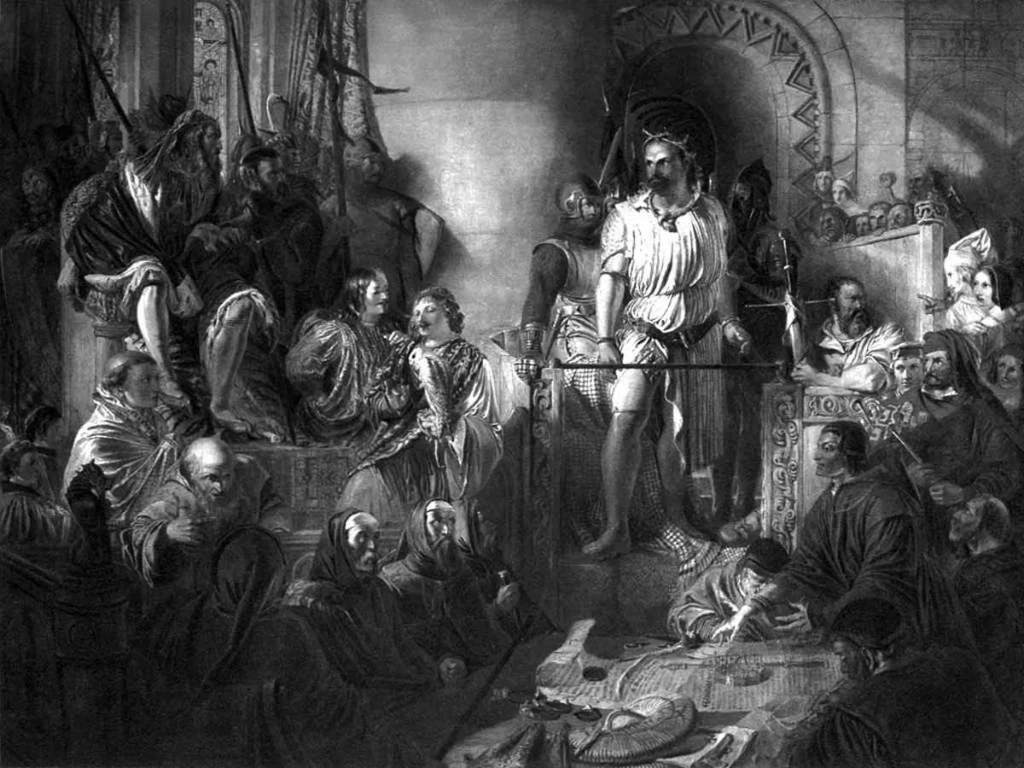

Outlawed and hounded—by English officials and by Scots who judged survival safer than loyalty—Wallace fought a final, flickering war: small skirmishes, narrow escapes, rumors of reappearance, the stubborn refusal to go gently. In August 1305, betrayal brought it to an end. Sir John Menteith, forever after “the False Menteith,” handed Wallace to the English. Wallace was held at Dumbarton, then hauled to Westminster for a trial whose verdict was set in ink before the first charge was read.

They called him traitor to the English crown; he answered that he had never bent the knee to it. They accused him of atrocities; their king had made a continent tremble with harsh example. But justice here was theater, not judgment. On August 23, 1305, William Wallace was hanged, drawn, and quartered—England’s cruelest ritual for England’s fiercest enemy. His head went to London Bridge; his limbs were scattered as warnings.

Warnings can backfire. A martyr stored in a nation’s memory is a spark preserved in salt.

Did Wallace “Save” Scotland?

Here the story could take the easy path: a hero dies, a nation rises, curtain falls. Reality insists on nuance. A year after Wallace’s death, Robert the Bruce—lord, rival, sometimes ally—made his own desperate bid, and over the next decade Scotland crawled from conquest toward a crown again. The decisive victory at Bannockburn came in 1314, long after Wallace’s bones had gone to dust. So how did Wallace “save” Scotland from Edward I?

First, he changed the grammar of resistance. Instead of measuring strength where England was strongest, he taught Scotland to pick its ground, thin out supply lines, and strike on terms of her own. The schiltron—deadly when sprung in ambush or on rough, constricting fields—would later be used more fluidly under Bruce. At Bannockburn, Scottish formations advanced at the right instant, compressing English cavalry into bad ground near the Bannock Burn (stream) and turning that close-knit spear hedge from shield into spearpoint. It is no stretch to trace that evolution back to Stirling.

Second, he made independence an organizing principle, not just a grievance. Wallace’s brief tenure as Guardian proved that governance could be carried on in Balliol’s name without Balliol’s presence. Trade could be reopened; letters could be sent to foreign ports; Scotland could act as a state among states. For a people told they were subjects, the act of governing themselves was itself a defiance.

Third, he built a story sturdy enough to stand weather. This isn’t mere romanticism. Nations live on logistics and laws, but they also live on stories large enough to absorb defeat. Wallace’s legend—reinforced by poems, statues, and, centuries later, celluloid—gave Scotland a hero who failed, learned, and then, by his example, helped others succeed. You don’t need every detail to be verifiable for the lesson to be usable.

And yet, we should be clear: Wallace did not single-handedly break Edward’s hold. He did not live to see independence ratified. He was the first chapter of a hard book, not its last page. To say he “saved” Scotland is to say he kept the possibility of Scotland alive when conquest seemed inevitable—and taught the skills that would eventually make possibility real.

Strategy Over Spectacle

Boil away the romance and you find a small, sharp set of strategic moves that explain his success:

- Choose the theater. Rivers, bridges, marsh, and forest multiplied the power of light infantry and reduced that of heavier English arms. At Stirling, geography did as much killing as steel.

- Compress the fight. The schiltron refused cavalry shock by denying the horse room and angle. Used defensively at Falkirk, it suffered under arrows; used at the right moment offensively—as at Stirling and later Bannockburn—it turned into a moving wall.

- Attack the tail to starve the head. Wallace’s raids south and his scorched-earth retreats north forced Edward’s armies to haul their own hunger. An army that spends its energy foraging is an army that can’t pursue.

- Keep the political center open. Serving as Guardian, Wallace showed that government and resistance could coexist—that taxes could be raised, justice administered, and envoys dispatched even amid war.

- Let the legend work for you. Even in his lifetime, Wallace’s reputation drew men to his banner. After death, it drew resolve from those who needed a reason to rise again.

None of these tactics was invulnerable. But together they added up to a method the English could never completely solve: fight on Scotland’s terms or bleed trying to impose your own.

The Bruce Connection

Robert the Bruce was not Wallace’s pupil in any formal sense; he was a rival prince with his own ambitions, his own sins, and a very different political base. Yet when Bruce rebuilt Scotland’s military strength, he reached for tools Wallace had field-tested: mobility, terrain, denial of supply, and schiltrons used cannily. The catastrophic waste of English cavalry at Bannockburn—where river, bog, and spear conspired—looks, in retrospect, like Stirling perfected.

Just as important, Bruce benefited from the moral infrastructure Wallace had laid down. Independence had a spokesman long before it had a king. The idea had lodged.

Why the Story Still Matters

Wallace’s life is a tight arc: a sudden rise from obscurity, a brief command, a crash at Falkirk, years of dark resilience, and a brutal end that turned defeat into myth. That shape is catnip for storytellers, but it also serves a social function. After the Union of the Crowns and later the Acts of Union, after the crushing of Jacobite revolts, Scotland still needed a figure whose loyalty predated those late binds. Blind Harry’s 15th-century poem The Acts and Deeds of Sir William Wallace poured gold leaf over the skeleton of history, and later writers—from Walter Scott to Robert Burns—added their own sheen. The legends did not invent the man; they conserved him, like a coin in a glass case, brightening as the room around it dimmed.

If myth sometimes claims deeds that belonged to others, history benefits by asking why a nation kept the story. The answer is not complicated. Wallace gave Scotland two priceless gifts: a way to fight and a reason to keep fighting.

Conclusion

Did William Wallace stride alone across the stage and sweep Edward I into the wings? No. He was checked and wounded, outmaneuvered at times, and finally destroyed. But to measure him only by what he failed to finish is to miss how much he began.

He saved Scotland by refusing the field the enemy demanded, by teaching his countrymen to use the land beneath their feet as an ally, by proving that government and resistance could be coiled around each other without strangling both, and by leaving behind a story that kept the blood hot after the body grew cold. When Bruce’s spearmen pressed their schiltrons forward at Bannockburn, when English cavalry found the ground turning traitor and the river closing like a trap, Wallace’s hand was there—not in command, but in memory.

The English crown would learn, again and again, that Scotland could not be reduced by numbers alone. That truth—clear as the light off the Forth on a September morning—was Wallace’s victory. And in that sense, the man history gave us and the legend we made of him joined hands to deliver the same verdict: Scotland could fight, learn, endure, and—eventually—win.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Were the Mongols Really Religiously Tolerant?

Dunsterforce: The Race to Baku, 1918

Plato’s Gorgias: Rhetoric, Morality, and the Pursuit of the Good Life

A Short Explain on the Fall of the Mongol Empire

How American Lend-Lease Trucks Fueled the Soviet War Machine in WWII

Good King Wenceslas: Beyond the Carol

Erie Canal and the Wedding of the Waters

Critique de Disputing Disaster de Perry Anderson

Understand the Biblical Symbolism of Prostitution

🎧 Sun Records: A Jukebox Revolution Forged in Memphis

Vortigern: The Controversial King of Post-Roman Britain

Julius Caesar and the Danger of Punishment Without Due Process