The Arctic is cold, dark, and deadly. Yet explorers kept going north—for trade routes, for science, and for glory. Here are five of the most interesting stories: a vanished British expedition, the first person to sail the Northwest Passage, a Greek who wrote about the far north in ancient times, a Dane who learned from Indigenous peoples, and an American pioneer long denied his due.

1) Sir John Franklin: The Expedition That Disappeared

John Franklin went to sea at 12 and became a Royal Navy officer. After the Napoleonic Wars, he turned to Arctic exploration. Britain wanted the Northwest Passage, a shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific that would speed trade to Asia. Franklin tried more than once, mapping coastlines but not finding the full route.

In 1845, he sailed again with HMS Erebus and HMS Terror—134 men, supplies for three winters, and orders to push through the ice. The ships were last seen in Baffin Bay on July 26, 1845. Then they vanished.

Dozens of searches followed. Evidence later showed the ships were trapped in ice near King William Island. The crews abandoned them in 1848; Franklin himself died on June 11, 1847. Notes and artifacts hinted at starvation, disease, and likely lead poisoning from tinned food or water systems. No one survived. For over a century the fate of the ships was a mystery—until 2014, when searchers found the Erebus wreck, and 2016, when they found the Terror. Franklin’s story warns how Arctic ice can crush even the best-planned mission.

What to remember: They aimed to force a path through the Passage and never came home. The Arctic won.

2) Roald Amundsen: “Last of the Vikings”

Norwegian Roald Amundsen chose the poles over medical school. At 27, he went south with the Belgica—the first expedition to winter in Antarctica. Then he turned north and did what Franklin never could: in 1903–1906 he sailed the small ship Gjøa through the Northwest Passage, learning sea ice and survival from local Inuit communities.

He planned to reach the North Pole next but lost the race to Robert Peary (a claim some still debate). So Amundsen pivoted and led the first expedition to the South Pole in 1911, traveling by ski and dog sled—about 2,000 miles in 99 days.

Amundsen returned to the Arctic with new ideas: if you can’t walk or sail it, fly it. After failed airplane attempts, he reached the North Pole by airship (a dirigible) on May 11, 1926, with pilot Umberto Nobile and a small crew. Two years later, Amundsen died in a plane crash while trying to rescue Nobile after another airship accident.

What to remember: Adaptable, relentless, and practical—Amundsen won by planning well, moving fast, and learning from Arctic peoples.

3) Pytheas: An Ancient Glimpse of the Far North

Arctic exploration didn’t start in the Middle Ages. In 325 BCE, Greek geographer Pytheas sailed from Massalia (today’s Marseille). He sought trade—especially tin—but also knowledge. He reached lands far north of what the Mediterranean world knew, possibly Thule (often linked to Iceland or northern Norway).

Pytheas wrote about a “frozen sea” and the midnight sun, when daylight lasts all night in summer. Some ancient writers doubted him, but these details match what we know about the Arctic Circle. His work is lost, but later authors quoted him, making Pytheas the first known writer to give southern Europeans a realistic picture of the far north.

What to remember: Long before icebreakers, Pytheas proved that curiosity can outrun fear—and that the Arctic had already entered human imagination.

4) Knud Rasmussen: The Anthropologist on a Dogsled

Danish-Greenlandic explorer Knud Rasmussen grew up in Greenland and spoke Greenlandic. Unlike many explorers, he focused on people. He wanted to meet Indigenous communities across the Arctic, learn their languages, hear their stories, and record their technology and beliefs.

To fund fieldwork, he founded the Thule Trading Post (in today’s Qaanaaq). Over 23 years he led seven expeditions. The greatest was the Fifth Thule Expedition (1921–1924). Instead of a ship, Rasmussen chose dogsled and foot, crossing more than 18,000 miles from Greenland across Arctic Canada to Siberia.

Rasmussen and his Inuit companions—Arnarulunguak and Qaavigarsuak—visited settlements, gathered artifacts, documented oral histories, and learned about sled design, hunting, and spirituality. The results filled ten volumes—a priceless record of Arctic life in the early 20th century. Rasmussen died in 1933 after food poisoning during his seventh expedition, but his museum and writings remain vital.

What to remember: He showed that exploration isn’t only maps and flags—it’s also listening, learning, and preserving cultures.

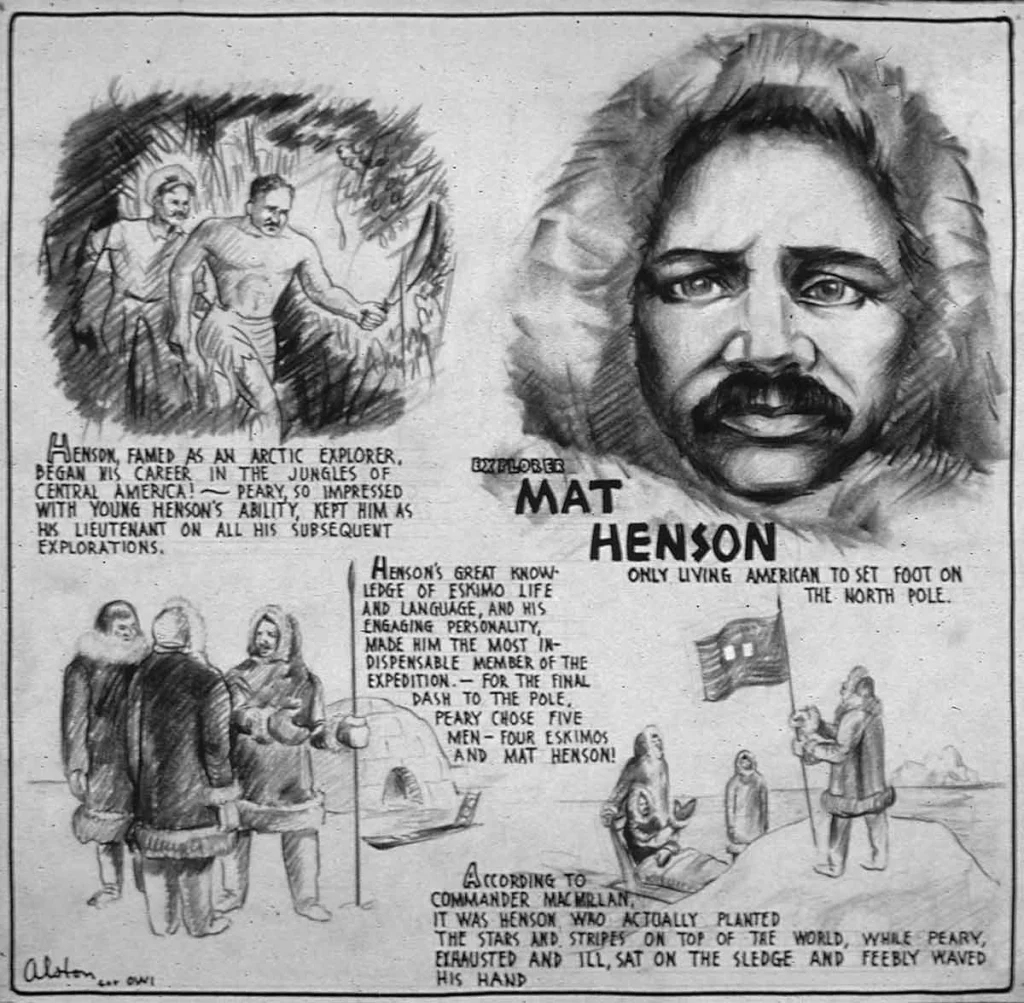

5) Matthew Henson: Co-Discoverer of the North Pole

Matthew Henson was born in 1866 in Maryland. Orphaned young, he worked as a cabin boy at 12, where a kind captain taught him reading, writing, and seamanship. After the captain died, Henson worked in a fur shop, met naval engineer Robert Peary, and was hired on the spot. Henson became Peary’s right hand: a master carpenter (building and repairing sleds), an expert with sled dogs, a skilled hunter, and a quick learner of the Inuit language.

From 1891 onward, Henson and Peary made repeated pushes toward the North Pole, each attempt going farther. In 1909, they finally reached their goal—though who stood exactly first at the Pole is disputed. Many accounts, including Henson’s, say he arrived ahead of Peary in the final dash.

In the racially segregated America of the time, Henson’s role was minimized. Recognition came late: The Explorers Club made him an honorary member in 1937; the U.S. Navy honored him in 1946; his headstone at Arlington National Cemetery now reads “Co-discoverer of the North Pole.”

What to remember: Henson’s skill and leadership were essential to the success. The Arctic remembers what history sometimes forgets.

What These Stories Teach Us

- Nature sets the rules. Franklin’s tragedy shows how the Arctic punishes poor odds, even with strong ships and supplies.

- Methods matter. Amundsen succeeded by planning for speed, using dogs, skis, and, later, airships.

- Curiosity is ancient. Pytheas reminds us the Arctic has drawn humans for over two millennia.

- Listen to locals. Rasmussen learned from Indigenous peoples and preserved their knowledge.

- Give credit fairly. Henson’s story proves that teamwork wins in the Arctic—and that recognition should match contribution.

The Event, in One Line for Each Explorer

- Franklin (1845–1848): Sailed to force the Northwest Passage; ships trapped and abandoned; all hands lost; wrecks found a century and a half later.

- Amundsen (1903–1906; 1911; 1926): First to sail the Northwest Passage, first to the South Pole, first to reach the North Pole by airship.

- Pytheas (325 BCE): Ancient sailor who reported ice seas and midnight sun—likely the first written glimpse of the Arctic for the Mediterranean world.

- Rasmussen (1921–1924): Crossed the Arctic by dogsled, documenting Indigenous cultures and languages across thousands of miles.

- Henson (1909): Co-discoverer of the North Pole, whose skill and leadership were crucial though long under-recognized.

Bottom line: The Arctic changes plans, tests character, and reveals truth. These five explorers show the many ways people have met that challenge—some by force, some by speed, some by listening, and some by simply refusing to give up.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

A Postscript to Greek Ethics

“O Jerusalem!”: Saint Louis, the Cross, and the Making of a Christian King

Armor of God: The Spiritual Warfare Blueprint Inspired by Roman Soldiers

Saint Patrick: The Life and Legends of Ireland’s Patron Saint

The Russian Apartment Bombings of 1999: Unraveling the Mystery

Hampton Court Palace: Is King Henry VIII’s Residence Truly Haunted?

From Jōmon to Yayoi: Japan Shifted from Foragers to Rice Farmers

The 1911 Champagne Riots in France

Who Gets to Call It Art? Inside the “Artworld” Theory

What Is Liberation Theology?

Bass Reeves: From Slave to U.S. Marshal

The Chremonidean War: Athens and Sparta’s Last Stand Against Macedon