Æthelflæd was born around 870 CE in Wessex, probably at the royal estate of Wantage, while England reeled under waves of Danish raids. Her father, Alfred the Great, was still a young prince; her mother, Ealhswith of Mercia, gave the child a double heritage—West-Saxon blood and Mercian sympathies. By the time Æthelflæd could walk, the “Great Heathen Army” had overrun Northumbria, East Anglia, and much of Mercia, forcing Alfred into a guerrilla refuge on the Somerset Levels. The daughter learned early that survival required fortitude, diplomacy, and—when talk failed—steel.

🤝 A Strategic Marriage and a Second Homeland

To seal a south-midland alliance after Alfred’s victory at Edington (878), Æthelflæd—now in her mid-teens—was married to Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians. The union joined Alfred’s resurgent Wessex to the surviving western half of Mercia and created a joint front against the Danelaw. At Worcester and Gloucester the couple endowed minsters, rebuilt walls, and hosted councils where West-Saxon reeves rubbed shoulders with Mercian ealdormen—an early rehearsal for political unification.

⚔️ Lady of the Mercians

Æthelred’s health faltered after c. 900; charters show his wife witnessing alone, and Mercian troops increasingly took their orders from her. When Æthelred died in 911, the witan proclaimed Æthelflæd “Myrcna hlædige” (Lady of the Mercians)—the only recorded case of an Anglo-Saxon kingdom inviting a female sovereign. Even her brother King Edward the Elder respected the decision, retaining London and Oxford but leaving the rest of Mercia under his sister’s independent hand. Contemporary chroniclers called her “a marvel to all the realm.”

🏰 Forging the Shieldwall of Burhs

Alfred had laced Wessex with earth-and-timber fortresses (burhs). Æthelflæd refined the concept into a forward strategy. Between 910 and 915 she sponsored or rebuilt at least ten strongpoints:

- Bridgnorth to guard the Severn crossing (912)

- Tamworth and Stafford to hem in Danish-held Leicester (913)

- Warwick and Eddisbury to bottle raiders from the Trent and Mersey valleys (914)

- Chirbury and Runcorn to seal the Welsh and Irish sea lanes (915)

Each site enclosed busy markets and mustering yards, turning Mercian towns into economic engines as well as bastions. Chroniclers joked she raised “one burh a year.” The network let small field armies march from wall to wall, resting and reprovisioning under watchtowers whose beacons could warn the next garrison within hours.

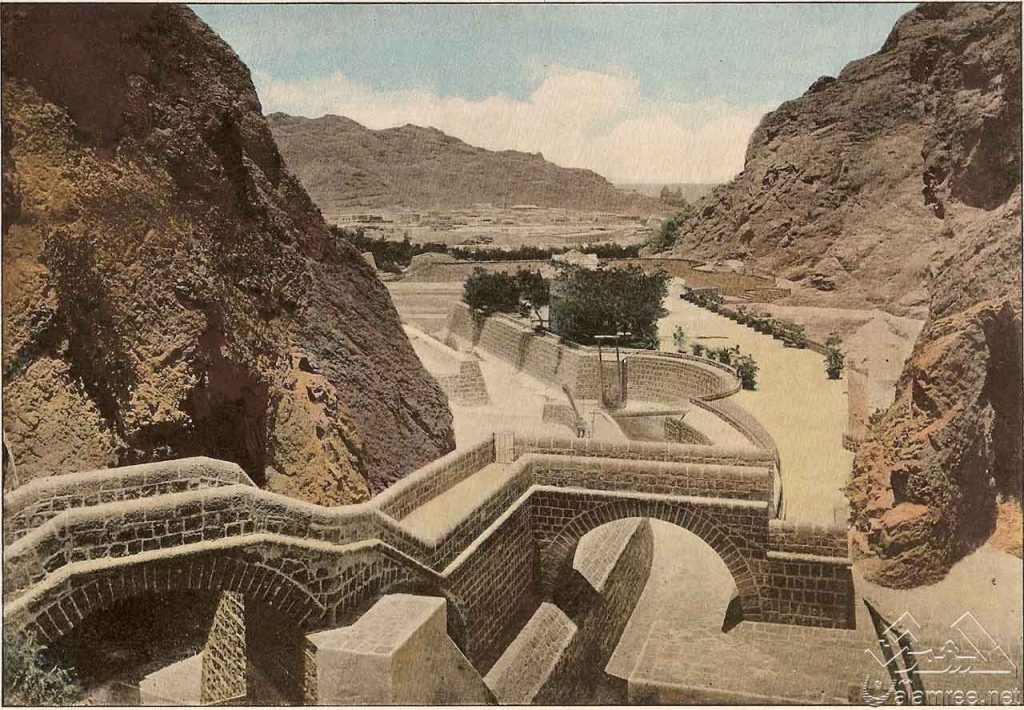

[Insert image here: “Map of Æthelflæd’s burh system overlying modern counties” — Caption: “A defensive necklace shielding Mercia and opening corridors for counter-offensives.”]

🛡️ Derby, Leicester, and the Fall of the Five Boroughs

In summer 917 Æthelflæd struck north with Mercian levies and West-Midland thegns. Derby, one of the Five Boroughs of the Danelaw, fell after bitter street-by-street fighting that cost the lives of “four thegns dear to her.” The next spring Leicester capitulated without a sword drawn, its jarls overawed by the new chain of forts hemming their fields. According to the Mercian Register, envoys from Viking-ruled York offered submission as well—unthinkable a decade earlier—but events outran intention. citeturn1search0

📜 Diplomacy, Alliance, and Cultural Patronage

Far from a mere warlord, Æthelflæd played the long diplomatic game. She forged pacts with King Constantine II of Alba (Scotland) and with the Strathclyde Britons, seeking a northern buffer against Norse Dubliners pressing into the Irish Sea. Welsh rulers paid her due respect; when a Mercian abbot was murdered in Brycheiniog (916), she ordered a surgical punitive raid, capturing the queen and thirty-three attendants—after which Welsh courts were careful to keep the peace. Inside Mercia she endowed scriptoria that copied saints’ lives and legal tracts, notably translating St Oswald’s relics from Bardney to Gloucester to boost both piety and Mercian prestige. citeturn1search0

💰 Governing a Reviving Heartland

The Lady kept a modest household, financing herself largely from estate rents rather than draining the Mercian tax—heregeld. Silver pennies from west-Mercian mints adopted unusual ornamental reverses—perhaps a subtle brand separating her currency from Wessex coinage. When she toured the burhs she sat in open folkmoots, adjudicating land disputes with a portable law-staff said to have belonged to Offa himself.

Burh residents paid no frontier tolls and enjoyed fixed grain prices in crisis years, encouraging merchants from Wales and Northumbria to settle behind the new ramparts. The arrangement fertilised what chroniclers called “the greening of Mercia,” a mini-boom that stocked arsenals and rewarded the garrisons that made it possible. citeturn1search0

⚓ A Broader Vision: Towards an English Polity

Æthelflæd saw the reconquest of the Danelaw not merely as frontier tidying but as laying rails toward a united English kingdom. Her Mercian troops fought beside Edward’s West-Saxon fyrd in joint operations—an embryonic national army. When York’s council courted her allegiance in 918, she stood ready to project power onto the Humber and complete the encirclement of Viking Northumbria. Had she lived a year longer, the title “Queen of the English” might have appeared in charters decades before Æthelstan.

🪦 Sudden Silence at Tamworth

On 12 June 918 CE Æthelflæd died at Tamworth, possibly from a sudden infection caught while inspecting the half-built burh at Stafford. The Mercian army bore her body to Gloucester, laying her beside her husband in the crypt of St Oswald’s. Chroniclers note a stunned hush: “Never before had so gentle a frame carried so firm a will,” wrote one scribe. Her only child, Ælfwynn, briefly succeeded but by Christmas King Edward had taken her into Wessex custody and absorbed Mercia outright. citeturn0search0turn1search0

🌟 Memory, Myth, and Modern Rediscovery

Medieval writers from William of Malmesbury to the Irish Three Fragments hailed the Lady as “the delight of her subjects and the dread of her foes.” Yet West-Saxon annalists muted her deeds, wary of reviving Mercian separatism. Only fragments in a lost Mercian Register kept her story alive. Victorian antiquarians rediscovered her burh earthworks; in 2018, the 1100th-anniversary of her death, Gloucester and Tamworth staged funeral re-enactments before thousands. Feminist historians now cite her as proof that early medieval Europe could—however rarely—entrust sovereignty and battlefield command to a woman.

🧭 The Compass She Set for England

Æthelflæd inherited a frontier province hemmed in by Danes and transformed it into the hinge on which England would later swing into being. Her burhs redirected trade, her armies broke the Five Boroughs, and her diplomacy knit Welsh, Scots, and Anglo-Saxons into a loose but unprecedented coalition. Though her reign lasted only seven years, the ramparts she raised and the precedents she set allowed her brother and nephew to finish the work of unification.

To walk the grassy embankments at Warwick, Stafford, or Tamworth today is to trace the outline of a vision that outlived its maker: an England defended by walls, but dreaming beyond them. The tale of Æthelflæd, Warrior Queen, reminds us that statecraft is sometimes written not by the longest-ruling monarchs, but by those who, in the brief span granted them, point a people toward a larger, shared horizon.