Egyptian art is easy to recognize: calm faces, steady poses, and perfect order. That look was not an accident. It came from a core idea the Egyptians lived by called ma’at—harmony, balance, and right order in the world. Art was made to keep that order. It was beautiful, yes, but it was also useful: statues housed spirits, amulets protected people, temple walls taught and praised the gods, and tomb paintings helped the dead live well in the next world. Keep that purpose in mind and the whole story of Egyptian art becomes clear.

Beginnings: Rock Carvings and a New Kingdom (Before the Kingdoms)

Long before the great pyramids, people in the Nile Valley carved animals, humans, and strange spirit figures into rock walls. These first images were simple, but they already showed a love of symmetry—left and right balanced like scales. Around 3150 BCE, Egypt formed as one country, and art took a big step forward. A famous object from this moment is the Narmer Palette. It’s a decorated stone slab that celebrates the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. On it, the king appears as both a mighty ruler and a sacred figure watched by the gods. The message is direct: the land is one, the king is strong, and the gods approve. The clean lines, clear story, and orderly layout would guide Egyptian art for centuries.

Old Kingdom: Monuments and a State Style

In the Old Kingdom (c. 2613–2181 BCE), a strong central government and growing wealth allowed artists and builders to think big. This is the age of the pyramids, the Great Sphinx, and fine stone statues. Relief carving—images raised a little from the background—covered tomb and temple walls. The style was formal and controlled. Why? Because the state set the rules. Kings and nobles ordered the work and expected a certain look: timeless, ideal, and calm. That is why statues from different workshops feel similar. The goal was not personal expression; it was to serve the king, the gods, and eternal life.

First Intermediate Period: New Voices, New Looks

After the Old Kingdom collapsed, Egypt entered the First Intermediate Period (2181–2040 BCE). For a long time, people called it a “dark age,” but that is not fair. The big building projects slowed because money and power were spread out. Local rulers and workshops made more of their own art. Styles changed from place to place. Some pieces were mass-produced, like wooden shabti dolls—little helpers meant to work for the dead in the afterlife. Before this, only the rich could afford them; now more families could. Quality could vary, but this era shows something important: when control loosens, variety grows.

Middle Kingdom: Skill, Feeling, and Daily Life

The Middle Kingdom (2040–1782 BCE) reunited Egypt under strong kings. Art stayed orderly but gained new depth. Craftspeople made exquisite jewelry and precise statues. Tomb scenes showed not only gods and rulers but also farmers, dancers, and workers. Even royal portraits became more realistic. King Senusret III appears at different ages and sometimes looks tired, a human touch rarely seen earlier. The focus of art tilted a little from perfect ideals toward the real life people knew: sowing fields, sharing food, hunting with dogs. The message is subtle but strong—earthly life matters.

Second Intermediate Period: Struggle and Exchange

During the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782–1570 BCE), foreigners known as the Hyksos ruled parts of northern Egypt while Thebes held the south. Art continued, often on a smaller scale. The Hyksos copied older Egyptian styles and also preserved texts and images that might otherwise have been lost. Contact with outsiders brought new ideas and techniques. Egypt was not a closed box; even in hard times, it learned from neighbors.

New Kingdom: Empire, Innovation, and Famous Faces

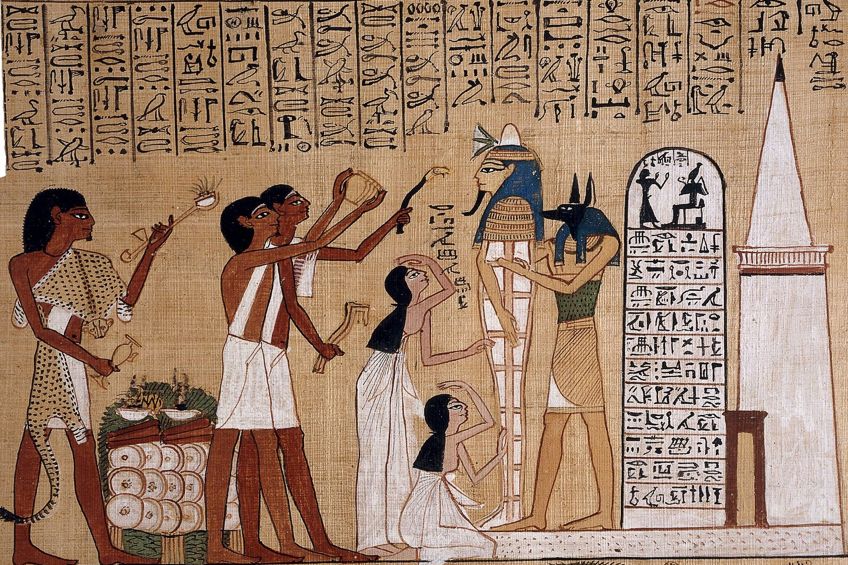

When Ahmose I drove out the Hyksos, the New Kingdom (c. 1570–1069 BCE) began. Egypt became an empire. Wealth poured in. Temples like Karnak grew into forests of columns. Colossal statues multiplied. People outside the royal household could now own copies of the Book of the Dead, richly illustrated with scenes to guide them after death. War and trade exposed artists to new metals, designs, and methods, especially from the Hittites, and this improved what they could do.

Two royal moments define this era’s style. Under Hatshepsut (1479–1458 BCE), art stayed elegant and somewhat ideal. Then Akhenaten (1353–1336 BCE) shook everything. He promoted the sun disk Aten and pushed a new, more realistic art: longer faces, softer bodies, family scenes with emotion. This is the Amarna Period, and it gave us two of Egypt’s most famous works: the bust of Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s queen, and the golden death mask of Tutankhamun. After Akhenaten died, Egypt returned to its older religion and more traditional style—but it kept the technical gains. The art remained masterful.

Later Periods: Tradition Meets Change

In the Third Intermediate and Late Periods (after 1069 BCE), Egypt often had less money and less central power. Even so, the art stayed skilled. Different rulers looked backward to the Old Kingdom for authority or forward to new forms. Kushite kings revived ancient styles to link themselves to Egypt’s deep past. Persian rulers respected Egyptian tradition and used its forms. Later, under the Ptolemies (Greek rulers) and then Rome, Egyptian and foreign styles mixed. You can see it in statues of blended gods like Serapis and in Roman-era tomb portraits that still follow Egyptian rules about balance and function. Egypt’s visual language proved flexible and durable.

What Held It All Together

Across three thousand years, the look of Egyptian art changed—sometimes a lot. Yet key things stayed the same:

- Purpose first. Art served religion, the state, and the journey after death. Beauty supported function.

- Balance and clarity. Compositions were stable and legible. You were meant to understand the scene at a glance.

- Timelessness. Figures rarely showed wild motion or passing moods. The goal was to capture the eternal, not the moment.

When foreign powers came, Egyptians adapted. They borrowed methods, metals, and motifs, then fit them into their own system. That habit—absorbing and reordering—helped Egyptian art survive and influence later cultures.

Why It Still Matters

Modern artists once tried to break all the old rules. But even the boldest experiments are easier to see and understand if you know where the rules began. Egyptian art laid down a model of order, meaning, and design that Europe and the Mediterranean followed for centuries. Columns, clear storytelling on walls, balanced figures—all of these trace back, in one way or another, to the Nile.

If you remember only one thing, make it this: Egyptian art was not just decoration. It was a working system built to keep the world in balance—on earth and beyond. From the Narmer Palette’s story of a new nation, to the quiet faces on tomb walls, to Nefertiti’s calm gaze, the message is steady across time: harmony gives life its shape, and art helps hold that harmony in place.

support our project

At History Affairs, we believe history belongs to everyone.

donateYour contribution helps us keep this global archive open, free, and growing — so people everywhere can learn from the past and shape a better future.

know the present

Defense Tech Needs the State, Not Less of It

Trump Era or The New Imperial Age

America First, Venezuela, and the Trap of Old Habits

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

reading more

Adam Smith: The Philosopher Who Revolutionized Economics

Why the AI Race Has No Winner

Ancient Greek Warfare Tactics Explained

Nicaragua’s Sandinista Revolution

The Clash of Titans: Rome vs. Antiochus the Great

How Rome Educated Its Slaves

5 Treaties Shaping History of Europe

Druids and the Soul of Wales

Healers, Helpers, and Hucksters: Who Treated the Plague in Medieval Europe?

How French Became the Language of Power and Prestige

Inside Japan’s Buddhist Temples

Why So Many Irish Immigrants Fought in the American Civil War